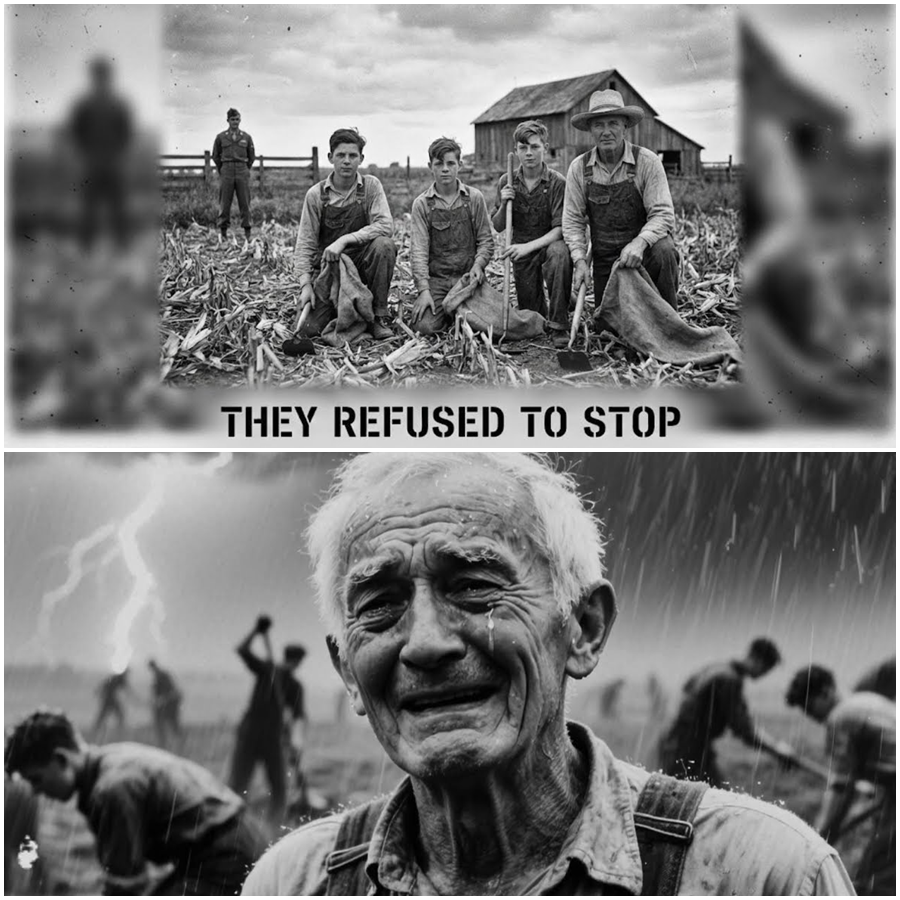

They Said German Child Soldiers Were “Forced” to Labor on American Farms, But What Investigators Discovered Later Was Far Stranger, Darker, and More Emotional Than Anyone Expected — A Buried Postwar Mystery of Silence, Survival, Unbreakable Will, Hidden Trauma, Moral Gray Zones, and Why These Children Refused to Stop Working Even When Told They Were Free

For decades, a troubling claim lingered quietly at the edges of postwar history: that German child soldiers were taken to American farms and used as labor. The phrase alone sounded explosive, even impossible. How could children from a defeated nation end up working the fields of a country that had fought against them? And more unsettling still—why did many of them refuse to stop working when officials later intervened?

The truth, as it so often is, turned out to be far more complex than the headlines suggest.

This is not a story of simple cruelty or simple kindness. It is a story shaped by hunger, fear, survival instincts, and psychological scars left by years of upheaval. It is about children who no longer knew how to exist without structure, and adults who struggled to understand whether they were helping or harming them.

What unfolded on isolated farms across rural America remains one of the least discussed chapters of the postwar era.

From Battlefields to Barnyards

When the war ended, Europe faced a crisis that went far beyond destroyed cities. Millions were displaced. Food was scarce. Families were separated, and countless children were left without clear guardianship. Among them were boys who had spent the final stages of the conflict in rigid, high-pressure environments that demanded obedience, endurance, and constant activity.

When transport and labor exchange programs quietly moved groups of youths overseas—often framed as rehabilitation or assistance efforts—many arrived in America not fully understanding where they were or what was expected of them. They were placed with farming families who needed help rebuilding food production during a period of labor shortages.

To outsiders, it appeared straightforward: young workers helping on farms in exchange for food, shelter, and supervision. But beneath the surface, something far more complicated was taking place.

A Generation Conditioned to Work or Collapse

These boys had been shaped by years of strict routines. Long days of physical exertion were not new to them. What was new was the absence of constant commands shouted through fear.

Farm owners noticed something unusual almost immediately. The boys worked relentlessly. They rose before dawn, volunteered for extra tasks, and resisted rest even when exhausted. When told to stop, some grew anxious. A few became visibly distressed.

Observers initially interpreted this behavior as discipline or gratitude. But psychologists later offered a different explanation: these children had been conditioned to equate constant labor with safety. Stopping felt dangerous. Idleness felt like threat.

Work, for them, was not exploitation—it was familiarity.

The Word That Sparked Outrage

Years later, when fragments of this history resurfaced, critics reached for the strongest language possible. They labeled the situation as forced labor. Some went further, using emotionally charged terms that ignited outrage but flattened nuance.

Yet records and firsthand accounts tell a more unsettling story. In many documented cases, local authorities attempted to reduce workloads, enforce rest periods, or relocate the boys to educational facilities. The resistance came not from the farmers—but from the youths themselves.

They insisted on staying. They begged to keep working.

The question then became deeply uncomfortable: if a child refuses freedom because work feels safer than uncertainty, what does freedom actually mean?

Farm Families Caught in a Moral Trap

American farm families were unprepared for what they encountered. Many had agreed to host young workers believing they were helping in a humanitarian effort. They expected fatigue, homesickness, perhaps resentment.

What they did not expect was emotional dependence.

Some boys followed their hosts constantly, seeking approval after every task. Others asked permission to eat, sleep, or sit down. Even small acts of kindness—warm meals, clean clothes—sometimes triggered emotional responses that confused their hosts.

Farm wives later recalled moments when boys apologized for eating too much or sleeping too long, as if survival itself required justification.

The families faced a moral dilemma: pushing the boys to rest seemed to cause distress, yet allowing nonstop work felt wrong. There was no handbook for this situation.

Silence Instead of Scandals

Why didn’t this become a major public controversy at the time?

Part of the answer lies in geography. These farms were remote. Another part lies in framing. Official descriptions emphasized rehabilitation and contribution, not coercion. And perhaps most importantly, the boys themselves rarely complained.

They did not see themselves as victims.

For many, the farm represented stability. Regular meals. Predictable days. Adults who did not shout or punish unpredictably. Compared to what they had known, this felt like peace.

That does not mean the situation was harmless—but it explains why it remained largely invisible.

When Authorities Tried to Intervene

As international standards evolved and child welfare concerns gained prominence, inspections increased. Some officials were alarmed by the intensity of the work performed by minors. Orders were issued to reduce labor hours and increase schooling.

What followed surprised everyone.

Several boys reacted with panic. Some ran away temporarily, returning to the farms on their own. Others became withdrawn or aggressive when removed from work routines. Counselors documented symptoms of deep anxiety triggered by sudden inactivity.

In one report, an inspector noted: “They appear to fear rest more than exhaustion.”

The realization forced authorities to rethink their approach. The issue was not simply physical labor—it was psychological survival.

The Hidden Cost of Early Conditioning

Experts later concluded that many of these children had never been allowed to develop normal emotional autonomy. Their identities were built around usefulness. Being productive meant being safe.

On American farms, this pattern continued—not through cruelty, but through misunderstanding.

Farmers praised diligence. They rewarded effort. They relied on help. Without realizing it, they reinforced the belief that worth came only through labor.

Breaking that cycle required time, therapy, and trust—resources that were scarce in rural settings at the time.

Stories That Emerged Decades Later

Only years later did some of these boys—now elderly men—begin to speak about their experiences. Their memories were conflicted.

They described exhaustion, yes. But also relief.

They recalled feeling needed. They remembered barns as quiet refuges. They spoke fondly of meals shared at long wooden tables. Many insisted they were treated better than they had ever been before.

When asked about the accusations of exploitation, some reacted with anger. Others with confusion.

“We were not chained,” one man reportedly said. “We were afraid of stopping.”

Reframing Responsibility

This story challenges easy judgments. It forces uncomfortable questions about trauma, consent, and responsibility.

Can work be both refuge and burden?

Can care unintentionally cause harm?

Can children refuse freedom because freedom feels unsafe?

The American farm families involved were not villains in the traditional sense. Nor were the boys simply passive victims. Both were caught in the aftermath of a global catastrophe that left no clean outcomes.

Understanding this history requires resisting sensational labels and instead confronting complexity.

Why This Story Still Matters Today

Modern discussions about displaced children, labor, and rehabilitation echo many of the same themes. Well-intentioned solutions can fail if they ignore psychological realities. Removing a harmful structure without replacing it can cause distress rather than healing.

The experience of these boys reminds us that recovery is not just about changing environments—it is about reshaping internal beliefs formed under extreme pressure.

Their refusal to stop working was not stubbornness. It was survival logic shaped by fear.

A Legacy Written in Calloused Hands

Some of these former child workers went on to become farmers themselves. Others chose entirely different paths. Many credited their time on American farms with keeping them alive during a fragile period.

Yet nearly all carried invisible scars.

They worked hard their entire lives. Rest came late. Guilt followed idleness. The fields may have been left behind, but the habits remained.

History rarely records these subtleties. It prefers heroes and villains, chains and freedom. But real human experiences are rarely so simple.

The Truth Beneath the Headline

Were German child soldiers forced to work on American farms?

Some would say yes. Others would say no.

The more honest answer is harder to digest: they were placed in a system that met their immediate needs while quietly reinforcing their deepest wounds. They worked not because they were ordered—but because stopping felt like falling into an abyss.

And that, perhaps, is the most unsettling truth of all.

Not that they were made to work.

But that they did not know how to stop.