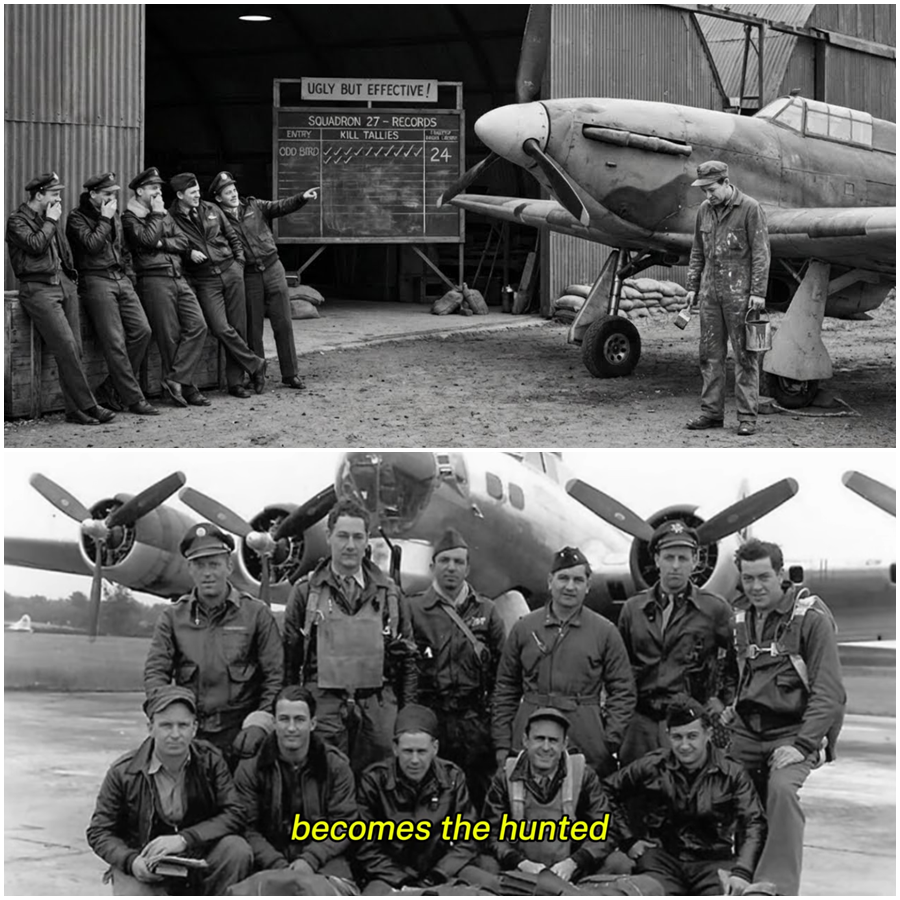

Squadron Mocked His “Ugly” Paint Job — Laughs on the Flight Line, Odd Colors Under Gray Skies, A Fighter That Looked Completely Wrong, Jokes Before Takeoff, Silence After Combat, Enemy Pilots Losing Sight Again and Again, Reports That Made No Sense, A Design No One Wanted, And a Strange Tactical Choice That Quietly Changed Air Combat Forever

On a crowded wartime airfield, surrounded by rows of perfectly uniform fighter planes, one aircraft stood out for all the wrong reasons. Its paint looked uneven. The colors didn’t match. From certain angles, it almost seemed unfinished.

Ground crews stared. Fellow pilots laughed. Someone nicknamed it “the flying mistake.”

The pilot didn’t argue. He didn’t explain. He simply listened, climbed into the cockpit, and flew.

What no one realized at the time was that this so-called “ugly” paint job would soon become one of the most quietly effective survival advantages in aerial combat—confounding enemy pilots, rewriting assumptions about visibility, and turning ridicule into reluctant respect.

This is the story of how an aircraft everyone mocked became the one no one could track.

The Culture of Uniformity in the Air

Fighter squadrons valued discipline, repetition, and predictability. Aircraft were painted according to regulations designed for identification, maintenance, and morale. Uniform colors meant faster recognition and fewer mistakes in the chaos of combat.

Deviation was discouraged.

Paint schemes weren’t just about appearance—they were about trust. A plane that looked wrong suggested risk. Risk meant danger, not just to the pilot, but to the entire formation.

So when one pilot requested permission to alter his aircraft’s exterior in a way that didn’t follow standard patterns, the response was predictable.

Skepticism first.

Then jokes.

Then open mockery.

Where the Idea Came From

The pilot behind the unusual paint job wasn’t trying to make a statement. He was trying to solve a problem.

In combat reports, a pattern kept emerging: enemy pilots were not always shooting accurately, but they were tracking targets effectively. Once locked visually, escape was difficult. Speed and maneuvering helped—but only to a point.

The pilot began to wonder if visibility itself was the issue.

What if the aircraft didn’t look like an aircraft anymore?

Studying the Sky, Not the Rulebook

During downtime, he observed the sky instead of manuals. Clouds were never one color. Light fractured constantly. Shadows shifted unpredictably.

Standard camouflage used solid patterns designed for ground concealment or formation recognition. But air combat happened in three dimensions, against backgrounds that changed every second.

The pilot noticed something else: the human eye didn’t lose targets because they disappeared—it lost them because they stopped making sense visually.

That insight changed everything.

Designing the “Ugly” Paint Job

The paint scheme he proposed broke nearly every aesthetic expectation.

Instead of clean lines, it used irregular shapes.

Instead of matching colors, it blended contrasting tones.

Instead of symmetry, it embraced imbalance.

Up close, it looked wrong. Distracting. Even careless.

But from a distance—especially at speed—it behaved differently.

Edges blurred. The outline broke apart. The aircraft didn’t disappear; it fragmented visually.

To fellow pilots, it looked ridiculous on the ground.

In the air, it became something else entirely.

The Squadron’s Reaction

The jokes were relentless.

“Hope the enemy laughs too hard to shoot.”

“Looks like it lost a fight with a paint bucket.”

“Good luck hiding that thing.”

The pilot accepted it all without comment. He knew there was no way to explain an idea that hadn’t yet proven itself.

Permission was granted only because supplies were limited and morale officers saw no harm in experimentation on a single aircraft.

No one expected results.

First Combat Test: Confusion in the Air

The first combat sortie didn’t feel dramatic from the pilot’s perspective. He flew as he always did—alert, cautious, aggressive when necessary.

But something strange happened.

Enemy fighters approached, then hesitated. Their maneuvers were delayed. Instead of closing confidently, they overshot or broke away.

The pilot noticed tracers passing where he had been, not where he was.

It wasn’t luck.

Something had changed.

Reports That Didn’t Add Up

After the mission, intelligence officers reviewed enemy engagement data. Claims were inconsistent.

Enemy pilots described targets that “shifted position suddenly” or “blended into cloud breaks.” Some reported losing sight of the aircraft entirely during standard maneuvers.

These weren’t inexperienced pilots. These were veterans.

The common factor was always the same aircraft.

The “ugly” one.

Why the Paint Worked

The paint scheme exploited a weakness not in machines, but in perception.

Human vision relies on edges, contrast, and expectation. Fighter recognition training taught pilots to identify familiar shapes quickly.

This aircraft disrupted that process.

Its outline didn’t remain stable. Against clouds, it dissolved. Against sunlight, it fractured. Against dark backgrounds, it refused to form a clear silhouette.

Enemy pilots weren’t missing—it was worse.

They were hesitating.

And hesitation in air combat is often fatal.

From Mockery to Curiosity

As missions continued, the results repeated.

The pilot returned consistently.

Enemy encounters ended faster.

Wingmen noticed fewer pursuers sticking close.

The jokes faded. Curiosity replaced them.

Other pilots began asking questions—not publicly, but quietly.

What colors were used?

How were patterns chosen?

Did it affect maintenance?

The pilot shared what he knew. There was no secret formula—only observation and adaptation.

When Command Took Notice

Eventually, higher command noticed something unusual in the statistics.

One pilot showed a markedly lower rate of sustained enemy engagement. His aircraft took less damage. His survival rate exceeded expectations for the intensity of missions flown.

An inspection followed.

What they found wasn’t advanced technology or illegal modification.

It was paint.

Ugly paint.

Testing the Unthinkable

Trials were conducted under controlled conditions. Aircraft with standard paint were flown alongside modified ones at varying distances, altitudes, and lighting conditions.

Observers struggled to track the altered aircraft consistently. Even friendly pilots lost visual contact sooner than expected.

The results were undeniable.

Visibility wasn’t about color alone—it was about pattern disruption.

Quiet Adoption, Not Loud Praise

There was no public announcement. No official acknowledgment of earlier mockery.

But new paint schemes began appearing.

Not identical—but inspired.

Irregular shapes. Softer transitions. Designs that looked wrong on the ground but behaved differently in the sky.

The “ugly” concept spread quietly.

The Pilot Who Didn’t Brag

The pilot never claimed credit. He didn’t seek recognition or promotion.

For him, the point had never been approval—it had been survival.

Every mission returned from was proof enough.

He continued flying with the same paint scheme, now less ridiculed and more studied.

How This Changed Aerial Thinking

This experiment challenged a core assumption: that camouflage should aim to hide.

Instead, it aimed to confuse.

That idea would later influence not just paint, but aircraft shape, surface texture, and even formation tactics.

Breaking visual expectation became as important as speed or firepower.

The Human Side of Innovation

This story isn’t about paint.

It’s about how new ideas are treated in rigid systems. About how laughter often greets anything unfamiliar. And about how results, not opinions, determine truth in the end.

The pilot didn’t win over his squadron with words.

He did it by coming back alive.

Why This Story Stayed Quiet

There were no dramatic battles tied solely to the paint scheme. No single moment of victory that demanded headlines.

Instead, there were dozens of small survivals. Missed shots. Lost visual contact. Pilots who made it home.

Those outcomes rarely make history books.

But they change lives.

Lessons That Still Matter

Even today, this story resonates beyond aviation.

It reminds us that effectiveness doesn’t always look impressive. That innovation often appears ugly before it proves beautiful. And that ridicule is not evidence of failure—just unfamiliarity.

The sky doesn’t care how something looks on the ground.

Only how it performs when it matters.

Conclusion: From Ugly to Unforgettable

“Squadron Mocked His ‘Ugly’ Paint Job” sounds like the setup to a joke.

Instead, it became a quiet turning point.

An aircraft that looked wrong saved its pilot again and again—not by hiding, but by confusing. Not by blending in, but by breaking expectation.

In war, as in life, the most effective solutions are often the ones no one wants to believe in—until they work.

And when they do, the laughter stops.

Because survival has a way of redefining what “ugly” really means.