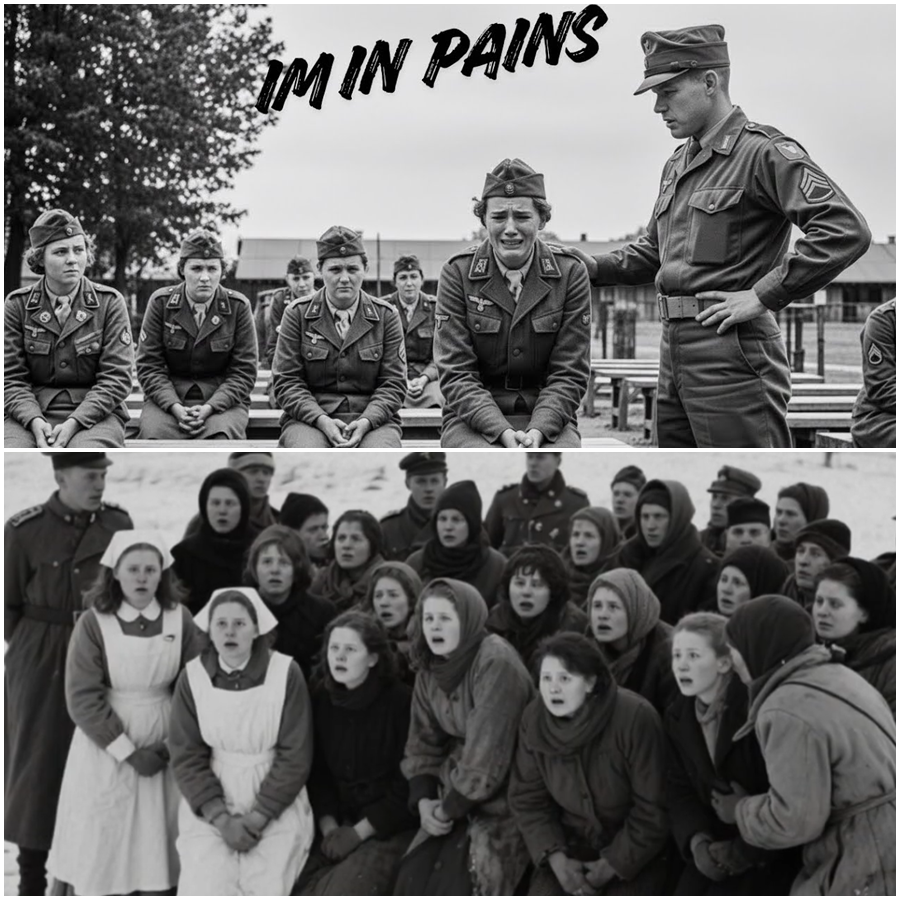

She Whispered It Hurt Every Time She Sat Down Inside an Allied POW Camp as German Female Prisoners Faced a Disturbing Reality That Few Dared Describe A Hidden Wartime Chapter Exposing Power Silence Fear and the Unspoken Cost of Captivity That History Softened Then Forgot Until Fragments of Records and Memories Slowly Revealed a Shocking Truth Buried Beneath Victory and Flags

“It hurts when I sit.”

The words were spoken quietly, almost apologetically, by a young German woman inside a prisoner holding facility run by the United States Army during the final phase of the Second World War. She was not shouting. She was not accusing. She was simply stating a physical fact, one that unsettled the medic who heard it far more than any dramatic outburst could have.

In that single sentence lay a world of questions—about treatment, authority, silence, and what happens to vulnerable people when systems are stretched thin by war.

For decades, stories like hers existed only as fragments: scattered medical notes, vague testimonies, and memories softened by time and fear. They were rarely discussed openly, not because they lacked importance, but because they sat uncomfortably close to a victory narrative that left little room for moral ambiguity.

Captivity After Collapse

When the European conflict drew to a close, hundreds of thousands of German personnel fell into Allied hands. Among them were women—clerks, nurses, radio operators, factory auxiliaries, and administrative staff who had been absorbed into wartime service as the conflict escalated.

These women were not front-line fighters, yet they were suddenly classified as prisoners. Transported across shattered landscapes, they were placed in hastily organized camps meant to process unprecedented numbers of detainees.

The system was overwhelmed.

Facilities designed for short-term holding became long-term environments. Guard rotations changed frequently. Oversight was inconsistent. Procedures varied from camp to camp.

And within that instability, discomfort—both physical and psychological—grew.

The Shock of the Unexpected

Many of the women arrived expecting harsh conditions: hunger, cold, uncertainty. What shocked them was not deprivation alone, but confusion.

Rules were unclear.

Boundaries shifted.

Authority felt absolute, yet strangely distant.

For women raised in rigid structures, the sudden inversion of power was deeply disorienting. They were instructed when to stand, when to sit, when to speak, when to remain silent.

And sometimes, when to endure discomfort without explanation.

Medical Complaints That Didn’t Fit the Forms

In postwar medical logs, researchers later found a pattern: repeated, vague physical complaints among female detainees that did not align neatly with recorded injuries or illnesses.

Pain when sitting.

Difficulty standing for long periods.

Requests for relief items denied or delayed.

These entries were often brief, clinical, and lacking follow-up. Not because medics were cruel, but because the system prioritized efficiency over nuance.

Pain that could not be easily categorized was often minimized.

The Power Imbalance No One Wanted to Name

War creates hierarchies where questioning authority becomes risky, even dangerous. For female prisoners, this imbalance was compounded by language barriers, cultural assumptions, and isolation.

Complaints were filtered through multiple layers of interpretation.

Tone mattered.

Timing mattered.

Perception mattered.

A woman who spoke too forcefully risked being labeled disruptive.

One who spoke too softly risked being ignored.

Many learned quickly that silence felt safer than misunderstanding.

What the Guards Saw—and Didn’t

Most guards were young men, recently removed from combat zones or awaiting redeployment. They operated under stress, fatigue, and orders that emphasized control.

The majority carried out their duties without overt malice. But even neutrality can become harmful in an environment where discomfort is normalized.

Small decisions accumulated:

A chair withheld.

A request delayed.

A complaint dismissed as exaggeration.

No single act appeared dramatic enough to trigger intervention.

Together, they formed a pattern.

When Pain Became Routine

For some detainees, physical discomfort became part of daily existence. Barracks benches were hard and unforgiving. Schedules allowed little flexibility. Rest periods were regulated, not responsive.

Pain was expected to be endured.

From an administrative perspective, this approach maintained order. From a human perspective, it erased individuality.

And for women experiencing ongoing discomfort, the inability to explain or resolve it deepened a sense of helplessness.

Why No One Spoke Publicly

After the war, attention shifted rapidly toward rebuilding, reconciliation, and celebration of victory. Stories that complicated the moral clarity of that moment were quietly sidelined.

Former detainees returned to shattered homelands.

Allied personnel reintegrated into civilian life.

Records were archived, summarized, or lost.

There was little incentive on either side to revisit uncomfortable details.

Silence became mutual.

The Difficulty of Language

One of the most overlooked aspects of this history is language itself.

Many women lacked the vocabulary to describe their discomfort clearly in a foreign tongue. Euphemisms replaced specifics. Gestures substituted for explanation.

What could not be precisely communicated could not be precisely addressed.

This gap between experience and expression widened over time, until memory itself began to blur.

Fragments That Survived

Decades later, historians uncovered letters never sent, diary entries written cautiously, and interviews conducted late in life where women spoke obliquely about captivity.

They did not accuse.

They did not dramatize.

They described sensations.

They described confusion.

They described pain that was real, even if its cause remained undefined.

These fragments do not form a single narrative—but together, they challenge simplistic versions of the past.

The Myth of the “Good Camp”

Some camps were later described as “well-run” or “humane” compared to others. Food was adequate. Violence was rare. Procedures existed.

Yet humane systems can still fail individuals.

The absence of overt cruelty does not guarantee the presence of dignity.

For those who lived with daily discomfort that went unacknowledged, the distinction mattered little.

Responsibility Without Villains

This story is not about assigning blame to specific individuals. It is about understanding how systems behave under strain.

Most guards followed rules.

Most medics did their best.

Most officers prioritized stability.

Yet pain persisted.

That contradiction is precisely why this history matters.

Why This Story Resurfaces Now

Modern discussions about wartime detention increasingly focus on lived experience rather than official policy. Scholars now ask not only what rules existed, but how they were felt.

The sentence “It hurts when I sit” survives because it is simple, human, and impossible to dismiss once heard.

It cuts through abstractions.

Memory Versus Narrative

Official histories tend to favor clarity: right and wrong, victory and defeat. Personal memories resist that structure.

They are uneven.

They are emotional.

They are often incomplete.

But they are also honest in ways official narratives cannot be.

Listening to the Quietest Voices

Female detainees occupied one of the quietest positions in the postwar record. Their experiences were neither dramatic enough to dominate headlines nor convenient enough to celebrate.

Yet their stories reveal how easily discomfort can be normalized when no one is looking closely.

Or listening carefully.

The Cost of Ignoring Small Pain

History often measures harm in extremes. But small, persistent pain—unaddressed, unexplained—can shape a life just as deeply.

It influences trust.

It influences memory.

It influences how individuals understand justice.

Ignoring it does not erase it.

Beyond Judgment, Toward Understanding

Revisiting this chapter is not about rewriting the outcome of the war. It is about widening the lens through which we view it.

Acknowledging complexity does not weaken history.

It strengthens it.

Because truth is rarely simple.

What Remains Unanswered

We may never know exactly what caused the discomfort described by those women. Records are incomplete. Time has passed.

What we do know is that their pain was real enough to be remembered—and quiet enough to be forgotten.

Until now.

The Sentence That Still Echoes

“It hurts when I sit.”

It is not an accusation.

It is not a verdict.

It is a reminder that even in moments of triumph, someone somewhere was enduring something unseen.

And history, if it is to be honest, must make room for that truth—even when it complicates the story we thought we knew.