German Prisoners of War Were Certain the American Winter Would Destroy Them—Starving, Freezing, and Isolated in a Land They Barely Understood—Until an Unlikely Group of Local Families, Farmers, and Small-Town Neighbors Did Something So Unexpected, So Human, and So Quietly Revolutionary That It Changed Survival Into Solidarity and Turned a Season of Fear Into One of the Most Astonishing Untold Stories of the War

For thousands of German prisoners of war captured during World War II, being sent to America felt less like rescue and more like a delayed sentence. They had crossed the Atlantic under guard, uncertain where they were headed, imagining unfamiliar dangers in a land painted by rumor and propaganda.

But nothing terrified them more than one simple fact.

They were arriving just before winter.

Many had come from temperate regions of Europe. Few had experienced the kind of brutal cold described by guards, whispered about by fellow prisoners, or exaggerated in wartime stories. Snowstorms. Endless ice. Temperatures so low they could end a life quietly in the night.

They believed winter itself might finish what the battlefield had started.

They were wrong—but not for the reasons they expected.

The Camps Built for Holding, Not Comfort

By late 1943 and early 1944, the United States held more than 400,000 German POWs in camps spread across the country. From Texas to the Midwest, from the Southwest deserts to the northern plains, these camps were meant to be secure, temporary, and functional.

They were not designed for comfort.

Barracks were basic. Clothing was standard issue. Heating systems were inconsistent, especially in camps hastily built to meet sudden demand.

When temperatures dropped, fear spread faster than frost.

Men huddled under thin blankets, unsure if the structures would hold against the wind. Many believed they had been sent north intentionally—as punishment.

Rumors filled the silence.

“Winter will finish us.”

“They don’t expect us to survive.”

“This is where they let nature decide.”

Propaganda Had Prepared Them for the Worst

Before capture, many prisoners had been told Americans were cruel, careless, and indifferent to suffering. The idea that captors would allow the cold to weaken or eliminate prisoners felt plausible.

No one expected mercy.

And certainly not kindness.

The First Snowfall

The first heavy snowfall hit unexpectedly.

Within hours, camps were transformed. Familiar paths vanished. Fences disappeared behind white walls. The world became quiet in a way that felt threatening rather than peaceful.

Men pressed their faces to frost-coated windows, watching the snow accumulate faster than they could imagine.

Some prayed.

Some wrote letters they doubted would ever be sent.

Some simply waited—certain they had reached the final chapter.

Then something strange happened.

The gates opened.

The Locals Who Changed Everything

In nearby towns and rural communities, Americans were facing their own winter challenges. Farms needed labor. Roads needed clearing. Animals needed care.

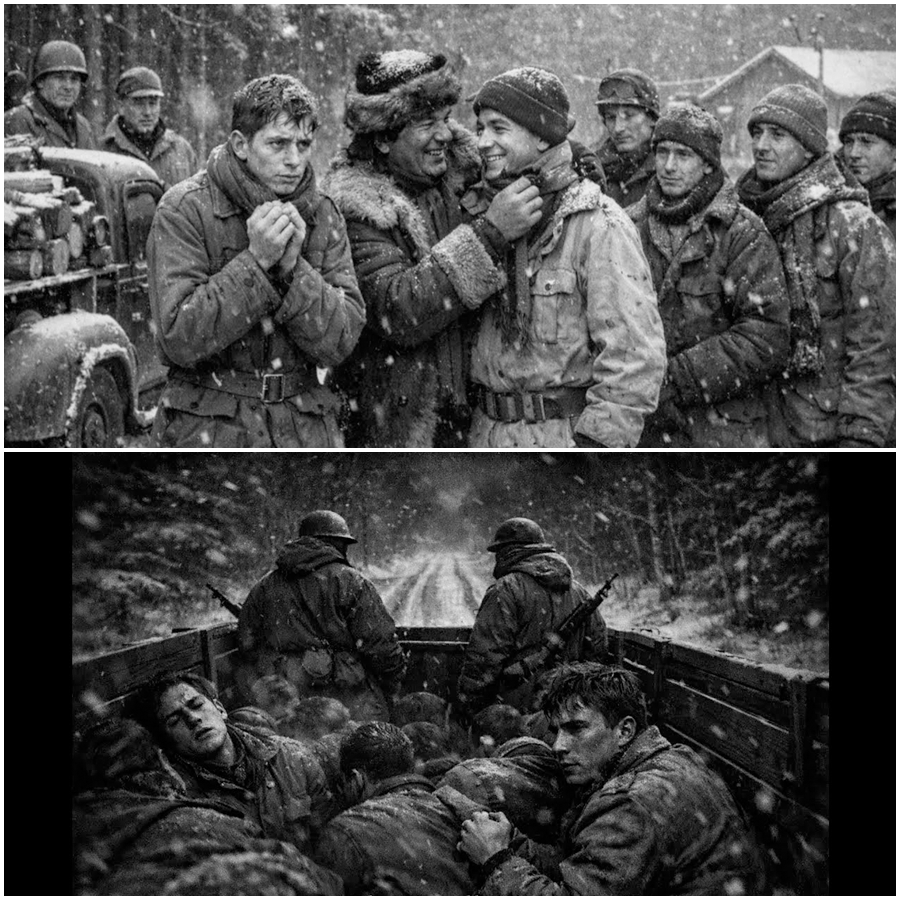

And across the snow-covered fields stood hundreds of prisoners—young men who, only months earlier, had been enemies.

Local officials had a choice.

Let fear rule.

Or let necessity—and humanity—lead.

They chose the second.

Work Details That Became Lifelines

Instead of confinement, prisoners were assigned to winter work crews. They cleared snow. Repaired barns. Cut firewood. Maintained roads.

At first, the POWs expected exploitation.

What they encountered instead was instruction.

Farmers showed them how to layer clothing properly. How to wrap cloth around boots. How to recognize frostbite before it became dangerous.

They were given hot drinks. Extra gloves. Advice passed down through generations of surviving harsh winters.

“You don’t fight the cold,” one farmer told them. “You respect it.”

That lesson saved lives.

The Unexpected Classroom: American Kitchens

Perhaps the greatest surprise came not from work—but from warmth.

In many regions, especially the Midwest, local families were permitted to host supervised meal breaks for POW work crews. Kitchens became places of cautious interaction.

German prisoners tasted hot stews thick with vegetables. Cornbread. Fresh milk. Food designed not just to fill, but to sustain.

They learned why Americans ate the way they did in winter.

Calories were armor.

Fear Slowly Gave Way to Understanding

Weeks passed.

Temperatures dropped further.

And yet—no one froze.

No one was abandoned.

No one disappeared in the night.

The winter they feared became manageable.

Not because it was mild—but because people showed them how to live through it.

Friendship Where None Was Expected

Conversations began cautiously.

A few words of broken English. A shared laugh over clumsy gestures. Stories about families left behind—spoken softly, carefully.

Farmers learned these men were bakers, teachers, mechanics. Not monsters.

Prisoners learned Americans worried about their own sons overseas just as deeply.

Winter has a way of stripping away pretense.

The Psychological Shift No One Anticipated

Survival changed how the prisoners saw captivity.

They were still prisoners.

Still guarded.

Still far from home.

But they were no longer convinced they were disposable.

That shift mattered.

It preserved morale.

It preserved health.

And in many cases, it preserved dignity.

How Local Knowledge Became the Difference

Americans taught them practical winter survival skills:

• How to insulate sleeping spaces

• How to dry clothing properly

• How to avoid dehydration in cold weather

• How to keep extremities safe

None of this came from manuals.

It came from experience.

And it worked.

The Winter That Didn’t Kill Them

When spring finally arrived, the prisoners realized something astonishing.

They had survived the worst winter of their lives.

Not through strength.

Not through resistance.

But through cooperation.

The Long-Term Impact Few Talk About

Many German POWs later wrote about their time in America. Winter often appeared as a turning point.

It was when they stopped seeing the United States as a place of punishment and began seeing it as a place of contradiction—capable of holding enemies without stripping them of humanity.

Some would later immigrate back after the war.

Others carried the memory home.

All carried the lesson.

Why This Story Was Buried

This story doesn’t fit easily into heroic war narratives.

There are no battles.

No triumphs.

No speeches.

Just quiet decency in the middle of a brutal season.

And that makes it easy to overlook.

The Final, Uncomfortable Truth

The German POWs were right to fear winter.

Cold is ruthless.

But they were wrong about Americans.

It wasn’t winter that decided their fate.

It was people.

Why This Story Still Matters

Because it reminds us that even in war, survival is often determined not by power—but by compassion.

That the harshest environments can be softened by shared knowledge.

And that sometimes, the most radical act is simply teaching someone how to stay alive.

A Season Rewritten

The American winter did not kill them.

It changed them.

And in doing so, it quietly rewrote what captivity—and humanity—could look like, even in the darkest chapters of history.