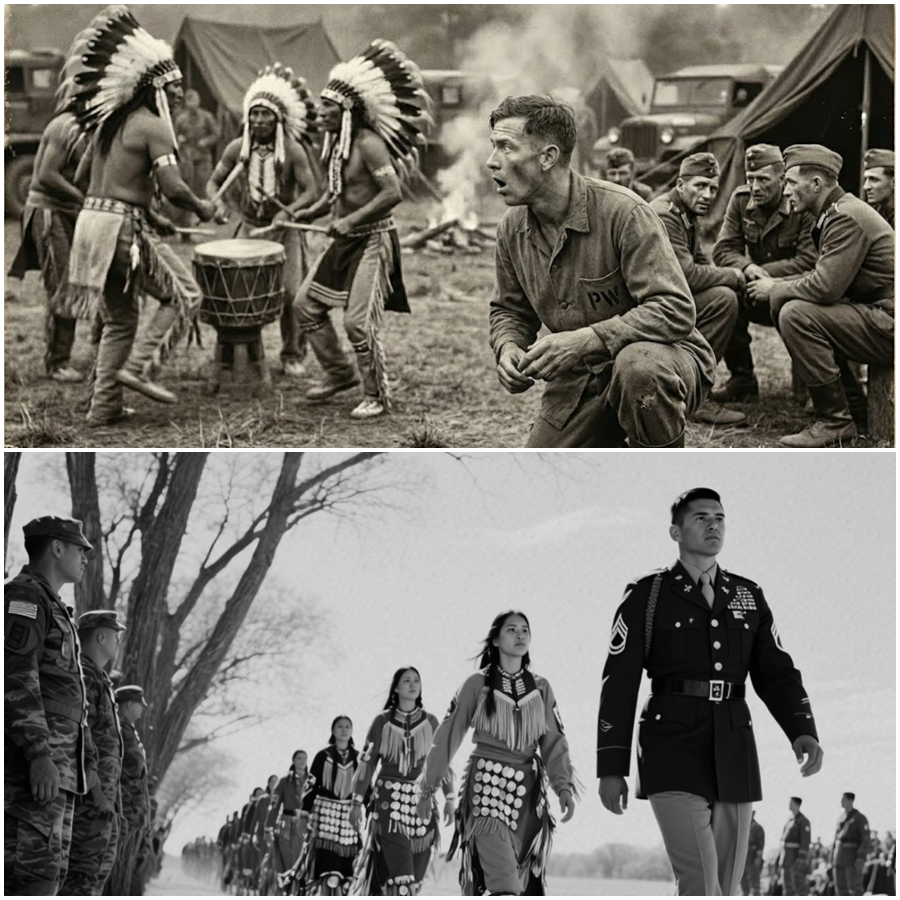

German POWs Held in Oklahoma Expected Isolation and Barbed Wire—Instead They Were Unexpectedly Taken to a Native American Powwow, Where Drums, Dances, and Ancient Traditions Shocked Them, Softened Years of Fear, Challenged Everything They Believed About Captivity and Enemies, and Created One of the Most Unlikely Cultural Encounters of the War That Few Histories Ever Mention

When people imagine prisoner-of-war camps, they often picture isolation, monotony, and rigid separation from the outside world. Few imagine music echoing across open fields, dancers moving in intricate patterns, or prisoners standing silently as they witness traditions far older than the nations now at war.

Yet in Oklahoma, during the later years of the conflict, something extraordinary happened. A group of German prisoners of war—men who had crossed an ocean under guard, uncertain of their futures—were escorted not to a labor site or another camp, but to a Native American powwow.

What unfolded that day stunned everyone involved.

Life as a POW in the American Midwest

By the middle years of the war, thousands of German prisoners were held across the United States. Camps were scattered through rural areas where land was available and security easier to manage. Oklahoma became home to several such facilities, surrounded by farmland, open skies, and communities unaccustomed to hosting foreign soldiers.

Life in these camps followed a strict routine. Prisoners worked, studied, exercised, and waited. For many, captivity in America was not physically harsh, but psychologically disorienting. They were far from home, surrounded by a language they barely understood, and dependent on the structure imposed by their captors.

Despite this, many POWs noticed something unexpected: predictability. Meals arrived regularly. Rules were clear. Guards were firm but often professional. Compared to the chaos many had left behind in Europe, the camps felt strangely stable.

Still, contact with local culture was limited.

An Invitation No One Expected

When camp officials announced that a group of prisoners would be taken on an escorted outing, confusion spread quickly. Rumors followed. Some expected farm work. Others assumed it was a morale exercise or a relocation.

No one expected what they were told next.

They were going to attend a Native American powwow.

For the prisoners, the words meant little. Few had any understanding of Native American cultures beyond vague stereotypes. They associated America with cities, factories, and military power—not with Indigenous traditions.

Skepticism mixed with curiosity as they boarded vehicles under guard.

The Powwow Grounds

The event took place on open land, decorated with banners, tents, and seating arranged in a large circle. As the prisoners arrived, the first thing they noticed was sound.

Drums.

Deep, rhythmic, resonant.

The sound did not resemble European military music. It did not signal command or warning. It pulsed steadily, carrying across the field in a way that felt both ancient and alive.

Prisoners stood quietly, uncertain how to behave.

First Impressions: Confusion and Awe

As dancers entered the circle in traditional regalia, the prisoners were struck by color and movement. Feathers, beadwork, bells, and patterned fabrics caught the light. Each step seemed deliberate, connected to something deeper than performance.

There was no sense of spectacle for spectacle’s sake.

This was ceremony.

Some prisoners whispered questions to one another. Others simply watched, transfixed. A few later admitted that it was the first time since capture that they had forgotten they were prisoners.

The Unexpected Welcome

What shocked the POWs most was not just what they saw—but how they were treated.

They were not hidden at the edge. They were not shamed or ignored. Organizers acknowledged their presence respectfully. Guards relaxed slightly, maintaining security without hostility.

At one point, a speaker addressed the gathering and spoke about endurance, history, and survival—concepts that resonated deeply with men who had seen their own world collapse.

Although translation was limited, meaning crossed the language barrier.

Shared Histories of Displacement

Some POWs later reflected on an unsettling realization: the people hosting this event had their own history of loss, displacement, and struggle with a powerful state.

They were not being presented with a simple image of “America.”

They were being shown complexity.

The idea that their captors’ country contained cultures that had endured conquest, marginalization, and survival challenged many assumptions they carried.

Why Camp Officials Approved the Visit

From the perspective of American authorities, the outing was not meant as entertainment. It was part of broader efforts to maintain morale, reduce tension, and demonstrate values distinct from those the prisoners had been taught to expect.

Exposure to American pluralism—its contradictions, its multiple identities—was considered a quiet form of re-education.

The powwow, with its emphasis on tradition and respect, served that purpose better than any lecture could.

Moments That Stayed With Them

Years later, former POWs would recall specific details vividly:

-

The steady rhythm of the drum that seemed to echo inside the chest

-

The dancers’ focus, unbroken by the presence of armed guards

-

Children running freely near the circle, laughing without fear

-

Elders seated calmly, watching with dignity

For men accustomed to constant vigilance, this atmosphere felt unreal.

Breaking the Image of the “Enemy”

War simplifies identities. People become symbols rather than individuals. The powwow disrupted that simplification.

The prisoners realized that America was not a single culture or voice. It was a layered society, containing histories older than the war and values that did not align neatly with military power.

This realization did not erase their loyalty or beliefs—but it complicated them.

Conversations Without Words

Despite limited language skills, interactions occurred. Smiles were exchanged. Nods of acknowledgment passed between dancers and spectators. Food was shared cautiously.

No one needed to explain everything.

Presence itself communicated respect.

The Emotional Impact on the Prisoners

Psychologists studying POW experiences note that moments of cultural connection can dramatically reduce feelings of dehumanization. When prisoners are treated as observers rather than objects, their sense of self stabilizes.

The powwow achieved this unexpectedly.

For a few hours, the men were not enemies.

They were witnesses.

Returning to Camp Changed

When the vehicles returned to camp, the routine resumed. Barbed wire still stood. Guards still counted heads. The future remained uncertain.

But something had shifted.

Prisoners spoke differently that evening. Less bitterness. More reflection. Some sketched what they had seen. Others tried to describe the experience in letters home.

The world felt larger again.

Why This Story Is Rarely Told

This episode rarely appears in official histories. It does not fit neatly into narratives of combat or diplomacy. It is small, human, and inconveniently complex.

Yet it reveals an essential truth about wartime captivity: not every interaction is defined by hostility. Sometimes, shared humanity emerges where no one expects it.

Native Hosts’ Perspective

Accounts from Native American participants suggest they saw the POWs not as representatives of an enemy nation, but as young men caught in forces larger than themselves.

Many elders emphasized hospitality and dignity—not to excuse war, but to assert their own values.

In welcoming prisoners, they demonstrated cultural strength rather than submission.

A Lesson About Identity

For the POWs, the powwow complicated their understanding of America. For Native participants, it reinforced their identity as distinct from federal power structures.

Both sides learned something uncomfortable and valuable: nations are not monoliths.

Long-Term Effects

Some prisoners later pursued academic studies in anthropology, history, or sociology, citing moments like this as formative. Others simply carried the memory quietly, a reminder that even in war, humanity can surface unexpectedly.

The experience did not make them forget the conflict.

It made them think about it differently.

Why This Matters Today

In a world still shaped by conflict, displacement, and detention, this story offers perspective. Exposure to culture, dignity, and mutual recognition can reduce fear where force cannot.

It does not solve wars.

But it changes people.

A Quiet Counter-Narrative

The powwow in Oklahoma stands as a counter-narrative to the idea that war erases culture. Instead, it shows culture persisting—and even bridging divides—under extraordinary circumstances.

Drums carried across a field once surrounded by fences.

And for a moment, the fences faded.

A Final Reflection

German POWs in Oklahoma arrived at a Native American powwow expecting nothing more than another controlled outing. What they encountered instead was history, resilience, and a reminder that identity is never singular.

In the rhythm of drums and the grace of dance, they glimpsed a world older than the war and larger than captivity.

It was not freedom.

But it was recognition.

And sometimes, recognition is the first step back toward humanity.