At 2200 hours on November 17th, 1944, Sergeant Mel Grevich stood in a storage warehouse at Camp Tarowa, Hawaii, staring at a row of damaged aircraft waiting to be scrapped. 26 years old, 18 months in the Pacific, zero innovations that had saved lives. His battalion had lost 11 machine gunners in the past 4 weeks during training exercises.

The problem was speed. The M1919 A6 light machine gun weighed 32 lb and fired 400 rounds per minute. German MG42s fired 1,200 rounds per minute. Japanese Type 92s fired 450. American Marines were outgunned. Grevich had watched three gunners die on Bugenville because they couldn’t lay down suppressive fire fast enough.

The enemy simply advanced through the gaps in their firing pattern. Grevich was assigned to G Company, 28th Marine Regiment, Fifth Marine Division. The regiment was preparing for the invasion of Ewima. Intelligence reports estimated 21,000 Japanese defenders dug into 11 mi of underground tunnels. The Marines would land on black volcanic sand with nowhere to hide.

Machine gun teams would be critical, but the M1919 A6 was too slow, too heavy, too vulnerable. Three weeks earlier, Grevich had approached his company commander. He explained that the M1919 A6 took three men to operate effectively. One gunner, one assistant gunner to feed ammunition, one ammo bearer to carry spare belts. If the gunner went down, the entire fire team collapsed.

The weapon was also difficult to reposition during an assault. Marines had to stop, set up the bipod, and then begin firing. By that time, Japanese defenders had already identified their position. The company commander listened. Then he asked Grevich if he had a solution. Grevich did. He had seen it work on Bugganville 13 months earlier.

In November 1943, he had been with the third parachute battalion. Marines had salvaged a M2 aircraft machine guns from crashed dive bombers. These weapons were designed to be mounted on SBD Dauntless aircraft. They fired 30 caliber rounds at,200 rounds per minute, three times faster than the M1919 A6. The barrels were lighter. The weapons were designed to be cooled by 300 mph air flow during combat.

On Bugganville, a Marine named Private Bill Colby had simply attached a bipod to an AM2 and used it as a ground weapon. It worked, but the weapon still had aircraft style spade grips. No stock, no proper trigger. It was functional but awkward. Gravich and his platoon leader, Lieutenant Philip Gray, had modified one A&M M2 more extensively.

They added an M1 Garand rifle stock, a bar bipod, a fabricated trigger. The weapon worked, but the third parachute battalion was disbanded before they could use it in combat. Grevich was reassigned to the 28th Marines. The modified A&M2 was left behind. Now in November 1944, Grevage stood in that warehouse remembering what that weapon could do.

The 28th Marines would land on Ewima in less than 3 months. The M1919 A6 wouldn’t be enough. He needed that AM2 modification, but this time he needed six of them. one for each rifle platoon in G company, one for the demolition section, one for himself. His company commander approved the project. So did the battalion commander.

Grevich was authorized to build the weapons. But there was a problem. He needed parts. Am2 receivers, M1 Garand stocks, bar bipods, trigger components, metal working tools, and he needed them without official requisition paperwork. The modification wasn’t standard issue. It wasn’t approved by Marine Corps ordinance.

If Grevich went through official channels, the project would be delayed for months, maybe years. He found private first class John Little. Little was a machinist. He understood tolerances and fabrication. Grevich explained what he needed. Little agreed to help. If you want to see how Grevik and Little managed to build six unauthorized machine guns in secret, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more forgotten stories from World War II. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Gravik. The two Marines began searching the base. They needed six A&M M2 receivers. These were controlled items. Aircraft armorament supposed to be accounted for and turned in when damaged. But thousands of aircraft have been lost in the Pacific.

Damaged, crashed, shot down. Some of those aircraft have been salvaged. Parts were sitting in warehouses waiting to be scrapped or shipped back to the mainland. Grevik and Little started asking questions. They visited maintenance depots, salvage yards, aircraft repair facilities. They found three A&M M2s in a parts bin labeled for scrap.

Two more in a damaged aircraft fuselage. The six they obtained from a source little later described as god knows where. By late November, they had six receivers, but they still needed stocks. bipods, sights, triggers, and they had less than 10 weeks before the division shipped out for Euima. Every night after regular duty, the two Marines worked in a makeshift shop, and every night they wondered if they’dfinish in time or if they’d be caught with unauthorized equipment before they ever got a chance to prove it worked.

The first modification began on November 21st. Grevich and Little worked in a corner of the battalion maintenance shed after dark. The A&M M2 aircraft machine gun weighed 23 pounds with its spade grips attached. The receiver was designed to be bolted into an aircraft mount. There was no provision for a shoulder stock.

No conventional trigger mechanism. The weapon was fired by pressing two butterfly triggers on the spade grips. This system worked perfectly in an aircraft turret. It was nearly useless for a Marine advancing across open ground. Little began by removing the spade grips. The grips were attached to the rear of the receiver with four bolts.

Once removed, the weapon had no way to be aimed or controlled. The next step was fabricating a trigger assembly. The ANM2 used an electrical solenoid to fire. Aircraft trigger sent to the solenoid. Little needed to create a mechanical trigger that would activate the same firing circuit. He fashioned a trigger from sheet metal, bent it to the correct angle, drilled mounting holes, attached a simple trigger guard made from scrap steel.

The trigger was crude, but it functioned. The stock was more complicated. The M1 Garand rifle stock was designed to fit the Garand receiver. The A&M M2 receiver had a completely different shape. The rear of the machine gun receiver included a buffer tube. This tube housed the recoil spring. It protruded several inches behind the main body of the weapon.

Little took a spare Garand stock and began cutting. He removed the forward section, hollowed out the rear portion to accept the buffer tube. The work required precision. If the stock fit too loosely, the weapon would be unstable. If it fit too tightly, it would crack under recoil stress. Little worked for 6 hours on the first stock.

He used hand tools, files, chisels, sandpaper. When he finished, the stock slid over the buffer tube with minimal clearance. He drilled holes for mounting bolts, attached the stock to the receiver. The weapon now had a shoulder rest, but it still lacked sights and a bipod. The BAR bipod was easier to install. The bipod attached to a mounting bracket on the barrel shroud.

Little fabricated an adapter plate from quarter-in steel. The adapter allowed the bar bipod to fit the ANM2 barrel. He welded the adapter in place. Tested the bipod deployment. It worked. The weapon could now be fired from a prone position. The rear sight presented another challenge. The ANM2 had rudimentary sights designed for aircraft use.

These sights were inadequate for ground combat. Little considered using BAR sights, but the BAR rear sight had its windage knob on the right side. The ANM M2 receiver configuration required the windage knob to be on the left. Little found M2 heavy barrel machine gun sights in the parts inventory. These sights had left side windage adjustment.

He modified the sight mount to fit the A&M2 receiver, attached it with screws to the top plate. The final modification was an ammunition feed system. The ANM2 was designed to be beltfed from aircraft ammunition bays. Marines couldn’t carry loose ammunition belts in combat. Little fabricated a 100 round ammunition box from sheet metal.

The box attached to the left side of the receiver. A standard cloth ammunition belt could be loaded into the box. The belt fed directly into the weapon. This allowed one marine to carry and operate the weapon without an assistant gunner. By December 5th, the first weapon was complete. Grevich and Little took it to a remote section of the base firing range. They loaded a 100 round belt.

Grevich shouldered the weapon, aimed at a target 50 yard downrange, pulled the trigger, the weapon fired. 1,200 rounds per minute. The sound was distinct, sharper than the M1919, faster. The recoil was manageable with the stock. The bipod kept the weapon stable. Grevich fired three 10 round bursts. All rounds impacted within an 18-in group.

But there was a problem. After 30 rounds, the barrel began to smoke. After 50 rounds, the barrel was too hot to touch. After 75 rounds, the weapon stopped firing. The barrel had expanded from heat. The A&M2 was designed to be cooled by air flow at high speed. On the ground, there was no cooling. The barrel overheated in less than 2 minutes of sustained fire.

Grevich and Little discussed solutions. They couldn’t add water cooling. That would add weight and complexity. They couldn’t change the barrel diameter. That would require machining equipment they didn’t have access to. The only solution was to change how Marines used the weapon. Short bursts, 5 to 10 rounds maximum, allow the barrel to cool between bursts.

It wasn’t ideal, but it was workable. By December 20th, they had completed three weapons. By January 5th, all six were finished. Each weapon weighed 25 lb, 7 lb lighter than the M1919 A6. Each fired three times faster. The weapons werepainted olive drab. Grevich named his weapon Betty Anne.

The others received similar names. The names were stencled on the receivers in white paint. On January 7th, 1945, the fifth Marine Division boarded transport ships in Hawaii. The six modified weapons were packed in equipment crates. No official paperwork documented their existence. No Marine Corps armorer had inspected them. No ordinance officer had approved them.

Grevich carried the maintenance manual for the standard A&M2 in his pack. He hoped it would be enough if anyone asked questions. The convoy sailed west toward the Japanese home islands. And Grevich wondered if his unauthorized machine guns would work in actual combat or if they’d fail when Marines needed them most.

The convoy stopped at any Wakato on February 5th. The Marines conducted equipment checks. Grevich inspected all six weapons. He test fired each one at a makeshift range on the island. All six functioned. The overheating issue remained, but the weapons fired reliably in short bursts, 5 to 10 rounds, pause, 5 to 10 rounds.

This firing pattern would work for suppressing pillboxes in enemy positions. On February 13th, the convoy conducted a practice landing on Tinian. This was the final rehearsal before Ewoima. Grevich brought all six weapons ashore during the exercise. He wanted to see how they performed during an actual amphibious assault. The weapons survived the landing, but the ammunition boxes took a beating.

Saltwater spray corroded the metal. Sand jammed the feed mechanisms. Gravich and Little spent 2 days cleaning and waterproofing the boxes. They wrapped the weapons in canvas tarps for the actual assault. On February 16th, the convoy arrived off the coast of Euoima. The island was 8 square miles of volcanic rock.

Mount Surabachi dominated the southern tip. Intelligence briefings estimated 21,000 Japanese defenders. Most were underground. The island had been bombed for 74 consecutive days. Navy battleships and cruisers had fired thousands of shells at the beaches, but reconnaissance photos showed the defenses were still intact. The plan called for the 28th Marines to land at Green Beach.

This beach was on the far left of the landing zone, directly below Mount Surabbachi. The regiment’s mission was to drive across the narrowest part of the island, cut off the mountain from the rest of the Japanese defenses, then assault and capture Surabbachi itself. The terrain was brutal. Black volcanic sand that absorbed mortar and artillery impacts, steep terraces that channeled attackers into kill zones, pillboxes, and bunkers covering every approach.

Gravich assembled his fire team on February 18th. He explained how the modified weapons worked. Short bursts only, never sustained fire. The barrel would overheat. The weapon would jam. Marines needed to fire, pause, fire, pause. Each gunner would carry 200 rounds in ammunition boxes. Additional ammunition bearers would carry spare belts.

The assistant gunners would monitor barrel temperature. If the barrel started smoking, cease fire immediately. The weapons were distributed. One went to first platoon, one to second platoon, one to third platoon. These were the rifle platoon of G company. One weapon went to the demolition section. Grevich kept the fifth weapon, Betty Anne.

He would carry it himself during the assault. The sixth weapon presented a problem. G Company had five weapons, but Grevich had built six. The extra weapon needed a gunner, someone who understood machine guns, someone who could be trusted with an unauthorized weapon. The battalion commander suggested Corporal Tony Stein. Stein was assigned to a company, 28th Marines, different company, but Stein had a reputation.

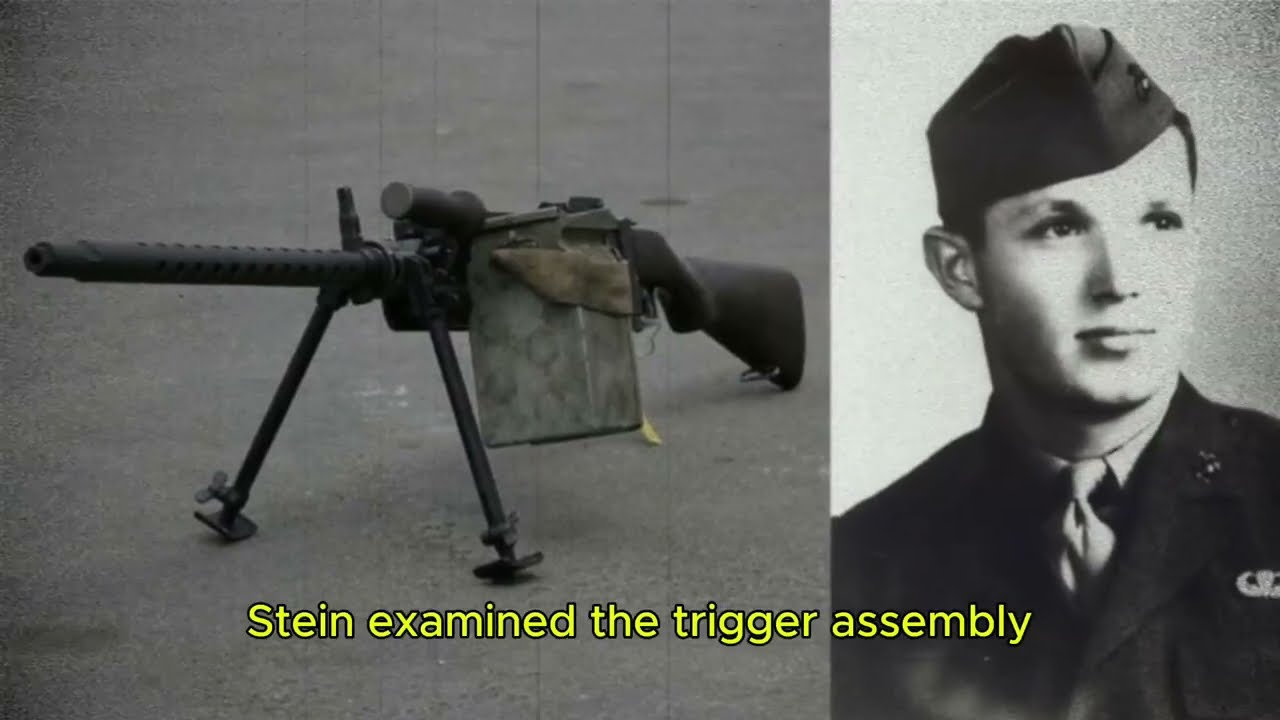

He was a toolmaker, a machinist from Dayton, Ohio. He had worked at Patterson Field and Delo products before enlisting. He understood mechanical systems. He had experience modifying equipment. Stein met with Grevich on February 18th. Grevitt showed him the weapon, explained the modifications, demonstrated the firing technique.

Stein examined the trigger assembly, the stock fitment, the ammunition feed system. He asked technical questions. How much clearance in the buffer tube? What grade of steel for the trigger guard, whether the bipod mount could handle repeated deployment stress? Gravich answered each question. Stein understood the weapon immediately. There was speculation later about why Stein received the sixth weapon.

Some believe Stein had helped with the construction, that he had assisted Grevich and Little during the fabrication process. Little never confirmed this. He only said that Stein was a machinist by trade, that Stein understood how the weapon worked, that he could be trusted to use it effectively.

The exact arrangement was never documented. On February 19th at 0400 hours, Marines began loading into landing craft. The naval bombardment had resumed at 0640. Battleships fired 16-in shells at the beaches. Cruisers fired8-in shells at the terraces above the landing zone. Destroyers moved within a thousand yards of shore and fired 5-in shells at pillboxes.

The noise was overwhelming, continuous. The entire island disappeared behind smoke and dust. Grevich stood in the landing craft with 42 Marines from G Company. Betty Anne was wrapped in canvas. The ammunition box held 100 rounds. He carried two additional belts in a pack. Total weight 47 lb. The M1919 A6 with tripod and ammunition weighed 56 lb and required two men to carry.

Gravich’s weapon was lighter, faster, and completely unauthorized. At 08:30, the landing craft formed assault waves. The bombardment lifted. Naval gunfire shifted to targets inland. The first wave headed toward Green Beach. Grevich’s craft was in the second wave, scheduled to land at 0915. He could see Mount Surabbachi ahead, 550 ft high, black sand beach at the base, smoke rising from the bombardment.

No visible enemy fire. The beach looked empty. Intelligence had predicted moderate resistance for the first few hours, then heavy counterattacks once the Marines moved inland. At 0900, the first wave hit the beach. Grevich watched from 800 yardds offshore. The landing craft dropped their ramps. Marines poured out, ran up the beach.

Still no enemy fire. The beach remained quiet. Grevich wondered if the bombardment had worked, if the Japanese defenses had been destroyed, if the landing would be easier than expected. 15 minutes later, he would learn exactly how wrong that assumption was, and whether his unauthorized machine gun could do what no regulation weapon could accomplish.

At 0912, Gravich’s landing craft crossed the line of departure. The beach was 300 yd ahead. The first wave had disappeared into the terraces above the water line. Still no enemy fire. The silence was unnatural. 42 Marines in the craft. Nobody spoke. The only sounds were the engine and waves hitting the hull.

At 0914, the craft was 100 yd from shore. Gravich could see the beach clearly now. Black volcanic sand, steep terraces rising 15 ft above the water line, damaged landing craft from the first wave, but no Marines visible. They had all moved inland. The beach looked abandoned. At 09:15, the ramp dropped. Grevich was the third marine out.

His boots hit waistdeep water. The sand beneath was unstable. Volcanic ash mixed with larger rocks. Every step required effort. The weight of Betty Anne and ammunition made movement harder. He pushed forward 20 yards to the beach, 15 yd, 10 yard. The first mortar round landed at 0916, 40 yard to Gravich’s left.

The explosion threw black sand 20 ft into the air. The second round landed 5 seconds later, 30 yards to his right. Then the beach erupted. Mortars, artillery, machine gun fire from hidden positions in the terraces. The Japanese had waited, let the first two waves land, allowed the Marines to bunch up on the beach, then opened fire from prepared positions.

Grevich reached the beach at 0917. He dropped behind a small rise in the sand, unwrapped Betty Anne, deployed the bipod, scanned for targets. The enemy fire was coming from pillboxes built into the terraces. Concrete reinforced positions with interlocking fields of fire. The pill boxes were invisible until they opened fire.

Then they disappeared behind smoke and dust. A marine 20 feet to Gravich’s right had an M1919 A6. The gunner was trying to set up the weapon. The assistant gunner was feeding the ammunition belt. Both were exposed. A burst of Japanese machine gun fire hit the assistant gunner. He went down.

The primary gunner grabbed the weapon and tried to reposition. A second burst hit him in the chest. The M1919 A6 fell into the sand. The fire team was eliminated in 8 seconds. Grevich identified the Japanese position. A pill box 70 yardd inland. Firing port 6 in high, 2 ft wide. He shouldered Bettyanne, aimed at the firing port, pulled the trigger. 10 rounds, 1 second.

The distinctive sound of the A&M2 cut through the noise of the beach. 1,200 rounds per minute. The tracer showed every fifth round. All 10 rounds impacted around the firing port. The Japanese gun stopped firing. Grevich paused, let the barrel cool for 5 seconds, acquired a second target, a machine gun position 80 yard to the left, fired another 10 round burst.

The position went silent. He shifted to a third target. Fired. Shifted again, fired. Each burst was deliberate, controlled, short enough to prevent overheating, long enough to suppress the target. The difference was immediately apparent. The M1919 A6 fired 400 rounds per minute. A 10 round burst took 1.5 seconds.

Bettyanne fired the same 10 rounds in8 seconds, half the exposure time, half the time for enemy gunners to acquire Gravich’s position. The higher rate of fire also created better suppression. Japanese defenders couldn’t return fire effectively when 1,200 rounds per minute were impacting around their position. Other Marines with the modified weapons began engaging targets.

Grevage could hear the distinctive sound of the A&M2s across the beach. Higher pitch than the M1919. Faster cycling. The six weapons were spread across Green Beach with different companies and platoon, but all six were firing. All six were working. By 0930, elements of the 28th Marines had pushed inland. The beach was still under fire, but the volume had decreased.

The modified weapons had suppressed enough positions to create gaps in the Japanese defensive fire. Marines exploited those gaps, moved forward, established positions in the terraces. Grevich’s ammunition box was empty. 100 rounds expended in 15 minutes. He reloaded with a fresh belt. The barrel of Betty Anne was hot.

Not critical yet, but approaching the limit. He would need to reduce his rate of fire. Give the barrel more time to cool between bursts. At 0945, a Marine runner reached Grevich’s position. The runner was from a company. He reported that Corporal Stein was engaging pill boxes on the right flank. Stein had already made three trips back to the beach for more ammunition.

Each trip, he brought a wounded marine with him. Stein was running without his helmet, without his boots, trying to move faster under fire. Grevich acknowledged the report. He wondered how long the weapons would last. The barrels were thin, designed for aircraft use with forced air cooling. Combat on Ewima was different.

Sustained fire, limited cooling, high ambient temperature from volcanic activity. The island itself was hot. Steam rose from cracks in the ground. The combination of combat heat and environmental heat was beyond anything the weapons were designed to handle. At 1000 hours, Grevich heard a different sound. Not the crack of rifle fire or the thump of mortars.

This was a scream, high-pitched, inhuman, coming from Japanese positions inland. Marines later reported hearing similar sounds throughout the first day. Some believe it was Japanese soldiers reacting to the modified weapons. The rate of fire was unfamiliar. The sound was unfamiliar. The effectiveness was beyond what they had encountered from standard American machine guns.

Whether the Japanese actually called them monster guns would never be confirmed, but the psychological effect was undeniable, and Grevich knew his weapon was working exactly as designed. The question now was whether it could sustain that performance for the days of fighting ahead. By 1100 hours on February 19th, all six modified weapons were in continuous use.

The gunners had learned to manage the overheating problem. 5 to 10 round bursts, 15-second cooling intervals. The technique worked. Barrels stayed within operating temperature. The weapons maintained function. The tactical advantage was significant. Standard American machine guns required a crew of three.

One gunner, one assistant to feed ammunition, one bearer to carry spare belts. The modified weapons required only one marine. The gunner carried the weapon and ammunition. The 100 round box eliminated the need for an assistant feeder. This meant rifle squads could maintain full strength while still having machine gun support. The weight reduction also mattered, 25 lb versus 32.

A marine could carry the weapon and still move quickly across broken terrain. The first platoon gunner engaged a pillbox complex northeast of Green Beach at 11:30. The position held three interlocking firing ports. Japanese defenders had clear fields of fire covering the approach to the terraces. The gunner advanced to within 60 yards, fired a 15 round burst at the center port, shifted left, fired at the second port, shifted right, fired at the third port.

Total engagement time 12 seconds. All three ports went silent. The platoon advanced through the gap. The second platoon gunner worked with a demolition team at 1200 hours. The team was tasked with destroying a concrete bunker built into the base of a terrace. The bunker had a steel door, reinforced walls.

The demolition team needed to place charges directly against the door, but Japanese fire from adjacent positions prevented approach. The gunner suppressed four positions in sequence. Short bursts, rapid target transition. The demolition team reached the bunker, placed charges, withdrew. The bunker was destroyed at 12:15.

The third platoon gunner encountered the overheating limit at 12:30. He had been firing almost continuously for 90 minutes. The barrel temperature exceeded safe limits. The weapon jammed. The gunner cleared the jam, attempted to resume firing. The weapon jammed again. He stopped, let the barrel cool for 10 minutes.

The weapon resumed function. But the incident highlighted the fundamental limitation. The ANM2 barrel was designed for short bursts in aircraft combat, not sustained ground fire. Gunners had to discipline themselves. Short bursts, long pauses. It was the only way to keep the weapons operational.

The demolition section gunner used his weapon to cover engineer teams clearing obstacles. Japanesedefenders had placed mines and wire obstacles across approach routes. Engineers needed to clear these obstacles under fire. The gunner provided suppression. He fired at Japanese positions, forced the defenders to take cover.

The engineers completed their work. By 1300 hours, three major obstacle belts had been cleared. The 28th Marines pushed deeper inland. Grevich continued engaging targets throughout the afternoon. Bettyanne had fired approximately 400 rounds by 1400 hours. The barrel showed signs of wear, heat discoloration near the chamber, slight warping along the length, but the weapon still functioned.

Gravich monitored the barrel carefully. He reduced his burst length to five rounds, increased cooling time to 20 seconds. The modified firing pattern kept the barrel within limits. Tony Stein’s performance on the right flank became notable by mid-afternoon. Stein was using his modified weapon to attack pill boxes directly.

His technique was aggressive. He would identify a pillbox, advance to close range, fire sustained bursts at the firing port, then rush the position with grenades while Japanese defenders were suppressed. The method worked, but it consumed ammunition rapidly. Stein made eight trips back to the beach for resupply by 1500 hours.

Each trip covered approximately 200 yards under fire. Each trip, he brought back wounded Marines who couldn’t walk on their own. The psychological effect of the weapons became apparent during the afternoon fighting. Japanese defenders responded differently to the modified weapons than to standard machine guns.

The rate of fire was triple what they expected. The sound was distinct, higher pitched, more intense. Several Marines reported hearing Japanese soldiers shouting during firefights. The exact words were unclear, but the tone suggested surprise or alarm. Whether this translated to actual fear was impossible to confirm. What was confirmed was effectiveness.

The six weapons had suppressed dozens of positions, enabled multiple advances, supported breakthroughs that standard weapons could not achieve. By 1600 hours, the 28th Marines had achieved their D-Day objective. They had crossed the 800yard neck of the island. Mount Surabachi was isolated from the main Japanese defenses.

The regiment had suffered heavy casualties, but they held their positions, prepared to assault the mountain the following morning. Grevich inspected Betty Anne at 16:30. The barrel was damaged. Heat stress had caused micro fractures along the chamber. The weapon was still functional, but it wouldn’t last much longer.

He estimated maybe two more days of combat before barrel failure. The other five weapons showed similar wear. Little examined each weapon that evening. His assessment was consistent. The barrels were failing faster than expected. The weapons had maybe 48 hours of service life remaining. After that, they would need replacement barrels. But there were no replacement barrels.

The A&M M2 aircraft gun wasn’t designed for field maintenance. If the barrels failed, the weapons were finished and the 28th Marines would be back to standard machine guns. Slower, heavier, less effective. Grevich wondered if six weapons in two days would be enough or if they’d burn out before the real fighting even began.

February 20th began at 0600 with a cold rain. The 28th Marines prepared to assault Mount Surabachi from three directions. The mountain was 550 ft of volcanic rock honeycombed with caves and tunnels. Japanese defenders had artillery positions, machine gun nests, mortar pits, all connected by underground passages.

The Marines would have to fight uphill across open ground with minimal cover. Grevich’s fire team moved out at 0730. Their mission was to suppress positions on the eastern slope while rifle squads advanced. Bettyanne had cooled overnight. The barrel still showed heat damage, but the weapon cycled normally during a pre-assault function check.

Grevich loaded a fresh 100 round belt. He calculated he had enough ammunition for 10 to 12 engagements before requiring resupply. The advance began slowly. Japanese positions opened fire from concealed locations, mortars, machine guns, rifles. The terrain channeled the Marines into narrow corridors. Every corridor was covered by overlapping fire.

The modified weapons became critical for breaking these defensive positions. Grevich would identify a Japanese machine gun. Fire a 10- round burst. The Japanese gun would stop firing. Rifle squads would advance 20 yards. Then another position would open fire. Grevich would suppress it. The process repeated continuously. By 0900, three of the six modified weapons had suffered malfunctions.

The first platoon weapon experienced a barrel split. The thin aircraft barrel couldn’t handle the sustained heat and pressure. The weapon was inoperable. The gunner switched to a standard M1919 A6. The rate of fire dropped immediately. The demolition section weapon had a feed mechanismfailure. Sand and volcanic dust had accumulated in the ammunition box.

The belt jammed during feeding. The gunner spent 15 minutes clearing the jam. The weapon resumed function but required constant cleaning. The third platoon weapon overheated critically at 0930. The gunner had been engaging targets continuously for 40 minutes. He didn’t allow sufficient cooling time between bursts.

The barrel temperature exceeded critical limits. Metal fatigue caused the barrel to warp. rounds began keyholeing. Accuracy degraded beyond useful range. The gunner attempted to continue firing. The weapon jammed permanently. He abandoned it and picked up a rifle from a wounded marine. Three weapons remained functional. Gravich’s Betty Anne, the second platoon weapon, and Tony Stein’s weapon on the western approach.

These three weapons carried the burden of machine gun support for the entire regiment during the morning assault. The loss of the other three weapons forced tactical adjustments. Rifle squads had to provide their own suppressive fire using M1 Garands and BARS. Advance rate slowed. Casualties increased. Gravich’s ammunition supply became critical at 1000 hours.

He had fired 600 rounds since 0730. His last ammunition belt had 75 rounds remaining. No resupply was immediately available. The beach was 300 yd behind the front line. Enemy mortar fire covered the route. Ammunition bearers couldn’t advance safely. Grevage had to conserve ammunition. He reduced burst length to three rounds, selected only critical targets, positions that directly threatened advancing Marines.

The second platoon weapon failed at 10:45. The trigger assembly broke. The sheet metal fabrication couldn’t withstand repeated firing stress. The trigger snapped off at the mounting point. The gunner attempted field repair. He tried to manually activate the firing solenoid. It didn’t work. The weapon was finished. The second platoon lost its machine gun support.

Betty Anne and Stein’s weapon were the last two functioning. Gravich was on the eastern slope. Stein was on the western slope. They couldn’t coordinate, couldn’t support each other. Each was isolated with his respective unit. Each had limited ammunition. Each had a damaged weapon that could fail at any moment.

Gravich’s last belt ran out at 11:20. 75 rounds gone in six engagements. The ammunition box was empty. He searched for resupply, found a wounded marine carrying spare belts for a standard M1919. The belts were compatible. Gravich loaded one, fired a test burst. Betty Anne cycled normally. He had 200 rounds remaining.

After that, the weapon became useless metal. The assault on Surbachi continued through the afternoon. Progress was measured in yards. Every cave entrance had to be cleared. Every pillbox destroyed, every tunnel sealed. The Marines used flamethrowers, demolitions, direct fire from tanks. The modified weapons, when they were still functional, had provided critical fire support during the initial advance.

But by midafter afternoon on February 20th, only two weapons remained operational, and both were running on borrowed time. By 1700 hours, the 28th Marines had advanced 200 yards up the mountain. They held positions halfway to the summit. Casualties were severe. The regiment had lost 430 Marines killed or wounded in 2 days.

The advance would continue the next morning, but Grevich knew Betty Anne wouldn’t last another day. The barrel was visibly warped. The receiver showed stress cracks. The trigger assembly was loose. He estimated the weapon had maybe 50 rounds of life remaining. After that, he would be carrying 25 lbs of inoperable equipment, and the 28th Marines would have one fewer weapon to break through Japanese defenses.

The Marines would take Surabachi, but they would do it with standard weapons. The modified guns had done their job. Now they were dying one barrel at a time, one engagement at a time until nothing remained but the idea that two Marines with hand tools had built something the Marine Corps armory never could. Bettyanne fired its last rounds on February 21st at 0815.

Gravich was suppressing a machine gun nest on the northern slope of Surbachi. He loaded his final ammunition belt, 50 rounds. He fired three 10 round bursts. The Japanese position went silent. Gravich attempted a fourth burst. The weapon jammed. He cleared the stoppage, pulled the trigger again. Nothing.

The firing solenoid had failed. Electrical connections severed by sustained vibration and heat stress. Betty Anne was finished. Grevich set the weapon aside. He picked up an M1 Garand from a wounded Marine. For the next 2 days, he fought with a rifle. The weapon he had spent 3 months designing and building had lasted 72 hours in combat. 3 days.

But those three days had mattered. Tony Stein’s weapon lasted longer. Stein continued using his modified gun through February 23rd. That was the day the 28th Marines reached the summit of Mount Sarabachi. A 40man patrol from E companymade the climb at 0800. They carried a small American flag.

At 10:20, the flag was raised on the summit. Photographers captured the moment. Later that afternoon, a second, larger flag was raised. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal photographed the second flag raising. That image became one of the most recognized photographs in American history. Stein’s weapon failed on February 24th.

Barrel fracture, complete structural failure near the chamber. The weapon literally split apart during firing. Stein was uninjured, but the gun was destroyed. He switched to a standard M1919 A6 for the remainder of the Surabbachi fighting. By February 26th, all six modified weapons were nonfunctional. Four had barrel failures.

One had a broken trigger assembly. One had a catastrophic receiver crack that rendered it unsafe to fire. The 28th Marines collected the damaged weapons. They were supposed to be turned into battalion armory for documentation, but the weapons were never officially registered. No serial numbers, no property books, no maintenance records.

The damaged weapons disappeared, possibly discarded with other battle damaged equipment, possibly buried in the volcanic sand. The exact fate was never documented. Stein returned to combat after Surabbachi was secured. The 28th Marines moved to the northern sector of the island. The fighting intensified. Japanese defenders had prepared extensive cave systems.

Machine gun positions covered every approach. Progress slowed to yards per day. Casualties mounted. On March 1st, Stein volunteered to lead a 19-man patrol. The mission was to locate and destroy a Japanese machine gun complex that had pinned down a company. Stein advanced with the patrol at 1400 hours. The patrol moved through broken terrain north of Hill 362A.

Japanese positions were concealed in caves and spider holes. The patrol took fire from multiple directions. Stein identified the primary machine gun position. He was firing a standard weapon now, not his modified gun. The rate of fire was slower, the suppression less effective. He advanced toward the position.

A Japanese sniper in a concealed position fired one round. The round struck Stein in the head. He died instantly. 23 years old, 14 days after landing on Euoima. The recommendation for Stein’s Medal of Honor was submitted on March 15th. His platoon commander wrote the initial citation. The citation described Stein’s actions on February 19th, the first day of the invasion.

Stein had been armed with a personally improvised aircraft type weapon. He had provided covering fire for his platoon, made eight trips to the beach for ammunition. Each trip, he carried wounded Marines to safety. He had killed at least 20 Japanese defenders, destroyed multiple pill boxes, stood upright under fire to draw enemy attention and locate their positions.

The citation made no mention of Grevich, no mention of little, no mention of the three months of work in Hawaii, no mention of the unauthorized fabrication, no mention of the other five weapons. The citation described the weapon as personally improvised. This implied Stein had built it himself.

The language was technically accurate. Stein had received the weapon. He had used it personally. But the phrase personally improvised suggested sole authorship, individual creation. That was incorrect. The Medal of Honor recommendation moved up the chain of command. Battalion commander approved it. Regimental commander approved it.

Division commander approved it. Fleet Marine Force Pacific Commander approved it. Pacific Fleet Admiral Chester Nimttz approved it. Chief of Naval Operations approved it. Secretary of the Navy approved it. President Harry Truman signed the final authorization. On February 19th, 1946, exactly one year after the landing, Stein’s widow received the Medal of Honor at a ceremony in Columbus, Ohio.

Governor Frank Louch presented the award. Admiral Richard Penoyer placed the medal around her neck. The citation was published in newspapers across the United States. The story focused on Stein, his bravery, his sacrifice, his improvised weapon. The narrative was compelling. A toolmaker from Dayton, who modified an aircraft gun and used it to save his platoon.

The story was true, but incomplete. Two other Marines had designed the weapon, built six of them, distributed them to gunners across the regiment. Those two Marines were never mentioned in the citation, never mentioned in the news coverage, never mentioned in the historical record that followed. Mel Grevich and John Little had created the weapon that earned Tony Stein a Medal of Honor, but history remembered only Stein.

The question was why and whether anyone would ever correct the record before the last men who knew the truth were gone forever. The reason Grevich and Little disappeared from history was simple. They survived. Stein died. The Medal of Honor is almost always during wartime. Of the 464 medals of honor awardedduring World War II, 324 went to men who died earning them.

The citation tells the story of the recipients final moments, the heroic action that cost them their life. That narrative is powerful, compelling. It captures attention. Grevich survived. He fought through the entire 36-day battle. He was wounded twice. Neither wound was serious enough for evacuation. He returned to Hawaii with the fifth Marine Division in March 1945.

The division prepared for the invasion of Japan, Operation Olympic, scheduled for November 1st, 1945. Japan surrendered in August. Grevich never spoke publicly about the modified weapons. He was discharged in 1946, returned to Mountain Iron, Minnesota, lived a quiet life, died in the 1980s. His obituary made no mention of the stinger. John Little also survived.

He fought on Euoima with H Company 28th Marines. He was at the base of Mount Surabachi during the flag raising. He saw both flags go up on February 23rd. After the war, he returned to civilian life, became a homebuilder in California. He rarely discussed his combat experience. In his later years, he confirmed his role in building the weapons, but he never sought recognition, never contacted historians, never pushed to correct the record.

He died in 2015. His obituary mentioned he was a decorated Eoima survivor, nothing about the stinger. The Marine Corps never officially adopted the modified ANM2 design. After Eoima, there were recommendations to produce the weapon in larger quantities, replace the bar in rifle squads, issue one modified weapon per platoon.

The recommendations went up the chain of command. Ordinance evaluators studied the concept. They identified the fundamental problem, the barrel. Aircraft barrels couldn’t sustain ground combat stress. The weapons worked for short engagements, but they failed after extended use. Replacement barrels would be required constantly.

The logistics were impractical. The Marine Corps continued using the M19119 A6 through the end of World War II. The weapon was heavy, slow, but reliable. It could fire continuously without barrel failure. That reliability mattered more than rate of fire. After the war, the Marine Corps developed new weapons.

The M60 machine gun entered service in 1957. It offered better portability than the M1919, higher rate of fire, quick change barrel system. The M60 incorporated lessons learned from weapons like the Stinger, but the Stinger itself was forgotten. Military historians discovered the Stinger story decades later. They found references in unit records after action reports mentioned modified weapons used by the 28th Marines, but the reports didn’t name Grevich or Little.

They credited Stein because his Medal of Honor citation was the most detailed documentation. Researchers assumed Stein built the weapon alone. The citation said, “Personally improvised.” That phrase led historians to conclude individual fabrication. It took years of additional research to uncover Gravich and Little’s role.

Interviews with surviving Marines. Examination of technical details. Analysis of who had the skills and access to build such weapons. Today, only one Stinger replica exists. It was built by the Canadian Historical Arms Museum for a television documentary. The replica required three months to construct. Modern machinists with full machine shops and reference materials needed 90 days to reproduce what Grevich and Little built with hand tools in 10 weeks.

The replica demonstrated the weapon’s effectiveness. 1,200 rounds per minute, manageable recoil, accurate fire, but it also demonstrated the overheating problem. After 75 rounds, the barrel exceeded safe temperature limits. The replica confirmed every detail of the historical accounts. The original six weapons were never recovered.

They disappeared on Euima, destroyed by combat, discarded as battle damage, buried in volcanic sand. None survived. No serial numbers were recorded. No maintenance logs preserved. The weapons existed for 3 months. They fought for three days, then they vanished. Only the story remained. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We are rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. stories about sergeants and machinists who saved lives with improvised weapons and three months of night work.

Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you are watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You are not just a viewer. You are part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served.

Just let us know you are here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Mel Grevich and John Little do not disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered and you arehelping make that