When Patton’s Final Radio Call Went Dead, Eisenhower’s Quiet Reply Triggered a Hidden Hunt That Nearly Split Allied Command in Two

The radio tent smelled like wet wool, hot metal, and the kind of coffee that never tasted fresh—only necessary.

Outside, the winter air pressed against the canvas like a heavy hand. Somewhere beyond the dark, engines coughed, boots crunched frozen mud, and distant artillery rolled like thunder that refused to move on. The front was restless. The lines shifted in inches and miles, and every decision felt like a coin toss with lives on both sides.

Inside, a young signalman sat rigid at the console, headphones clamped tight, fingers hovering over dials as if he could tune the war itself into clarity. A red bulb blinked on and off—steady, patient, relentless.

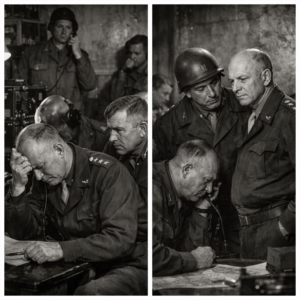

General Dwight D. Eisenhower stood at the map table, shoulders squared, expression composed. He had learned to look calm even when his mind was sprinting. The men around him—staff officers, aides, liaisons—watched his face the way sailors watched a lighthouse. If it stayed steady, they stayed steady.

The signalman suddenly raised a hand.

“Sir,” he said, voice cracking just slightly. “I’ve got Third Army.”

A ripple moved through the tent. Patton’s headquarters. Patton’s voice. That usually meant movement—fast, loud, unstoppable.

Eisenhower didn’t turn immediately. He let the room settle, let the men breathe. Then he stepped closer to the radio.

“Put it through,” he said.

The signalman adjusted the dial. The speaker hissed. Then came the voice—faint, clipped by distance and weather, but unmistakable. It had that sharp edge, like a blade scraping stone.

“This is Patton,” the voice snapped. “Listen—enemy armor… not where they say. I’m forward with a small element. Tell Ike I—”

The transmission cut.

No gentle fade. No polite end. It simply stopped, as if someone had closed a fist around the sound.

Static surged in its place—harsh, angry, drowning out everything.

The signalman’s eyes widened. He twisted knobs, tapped the console, leaned closer as if proximity could pull the voice back.

“General Patton, this is Supreme Headquarters,” he called into the mic. “Repeat last. Over.”

Only static answered.

Eisenhower stood perfectly still.

Across the tent, someone swallowed loudly. Another man shifted his weight, boots creaking. No one wanted to be the first to speak, because the first words after silence often became the shape of the story.

Eisenhower’s chief of staff, General Walter Bedell Smith, took one step forward. “Could be terrain, sir,” he said carefully. “Or weather interference.”

Eisenhower didn’t look away from the radio set.

Patton wasn’t the type to vanish into weather. Patton forced weather to move out of his way.

“How long since contact?” Eisenhower asked.

The signalman checked a log, hands trembling slightly. “Thirty-seven seconds, sir.”

Eisenhower nodded once, slow and deliberate.

“Raise him again,” he said.

The signalman tried. “General Patton, identify. Over.”

Static.

Again. “General Patton, respond. Over.”

Static.

Eisenhower leaned down and took the microphone himself. His hands were steady, but his knuckles showed pale beneath the skin.

“George,” he said, voice low and controlled. “This is Ike. Where are you? Over.”

For half a heartbeat, the speaker quieted—just enough that everyone in the tent leaned forward.

Then the static returned, louder than before, like laughter.

Eisenhower replaced the microphone on the hook.

The room waited for his reaction. For anger. For some kind of explosion to match Patton’s reputation.

But Eisenhower’s power had never been in volume. It was in decisions.

He looked at Bedell Smith and then, with no drama at all, he said, “Seal the tent.”

Men blinked. “Sir?”

“Seal it,” Eisenhower repeated. “No one walks out and starts telling stories about what they think happened. Not until we know.”

Two MPs moved to the flap. A staff officer quietly stepped outside and posted guards.

Eisenhower turned back to the map, and his finger moved across the paper, tracing roads and rivers with the precision of a man who understood that a single mile could be the distance between life and death.

“Where was Patton last confirmed?” he asked.

An operations officer stepped forward, pointing. “Here, sir—near the crossroads outside Houffalize. Reports say he went forward to confirm a gap.”

Bedell Smith’s jaw tightened. “With a small element,” he muttered. The words tasted like trouble.

Eisenhower’s eyes narrowed. “How small?”

“Two jeeps and a scout car, sir,” the officer answered. “That’s what his staff radioed earlier.”

A murmur moved through the room—half disbelief, half grim familiarity. Patton did things like that. He treated danger like an inconvenience.

Eisenhower studied the map a moment longer, then straightened.

And then he said it—the sentence that would later be repeated in whispers by men who claimed they had been there, men who swore they heard the Supreme Commander’s voice change.

But the truth was quieter, sharper, more dangerous.

Eisenhower spoke to the whole tent, yet his words felt like they were meant for one man alone.

“George Patton doesn’t go silent,” he said. “Not by accident.”

The tent went cold.

Bedell Smith’s eyes flicked toward the radio as if it might suddenly confess.

Eisenhower continued, voice steady as steel. “That means one of two things,” he said. “Either the enemy has found him… or someone behind our lines has.”

No one moved.

Because the second possibility was worse.

The enemy was expected. The enemy made sense. The enemy wore the right colors.

But “someone behind our lines” meant a different kind of fear—one with familiar boots.

Eisenhower turned to an aide. “Get me the provost marshal,” he ordered. “And intelligence. Now.”

The aide dashed out.

Bedell Smith stepped closer, lowering his voice. “Sir, if we treat this as… internal—”

Eisenhower didn’t let him finish. “If it’s external, we’ll know soon enough,” he said. “If it’s internal and we pretend it isn’t, we lose more than Patton.”

Bedell Smith’s face hardened. “We could lose command unity.”

Eisenhower’s eyes stayed on the map. “We could lose the war,” he replied.

He turned then, and his gaze landed on each man in the tent one by one, like he was counting them.

“I want a search,” Eisenhower said. “But I want it quiet. No panic. No rumor. No grand parade of vehicles.”

One officer protested cautiously. “Sir, with respect, if Patton’s been captured—”

Eisenhower cut him off. “Captured is a word you use when you plan to negotiate,” he said. “This is not that.”

The officer fell silent.

Eisenhower looked back at the radio, and for a moment, the tent held its breath again—waiting for some personal crack in the commander’s armor.

Instead, Eisenhower said the thing that surprised them all, because it wasn’t strategy.

It was a confession, spoken like a hard truth, meant to keep everyone honest.

“If Patton is gone,” Eisenhower said quietly, “there are people who will feel relieved.”

No one spoke.

Eisenhower’s voice sharpened. “And if anyone in Allied command feels relief at losing one of our own generals in the field, then we have a sickness that must be cut out—fast.”

Bedell Smith stared at him. “Sir…”

Eisenhower held up a hand. “Not in the papers,” he said. “Not in the history books. But in this tent, tonight, we tell the truth.”

The provost marshal arrived—a stout man with a tired face and a crisp salute. Intelligence officers followed, coats damp, eyes alert.

Eisenhower wasted no time.

“I want every report of stolen fuel, missing rations, black-market activity, unauthorized passes,” he said. “Anything that suggests men are using this war for profit or power.”

The intelligence officer blinked. “Sir, are you suggesting—”

“I’m suggesting,” Eisenhower said, “that Patton’s mouth is dangerous to the wrong people.”

The provost marshal cleared his throat. “Sir, we can deploy MPs to roadblocks.”

“Not yet,” Eisenhower replied. “If it’s the enemy, roadblocks won’t matter. If it’s ours, roadblocks will warn them.”

Bedell Smith frowned. “Then what?”

Eisenhower’s eyes narrowed. “We bait the net,” he said.

The search began like a whisper.

Two unmarked jeeps. A reconnaissance team that looked like it was merely checking road conditions. A radio truck that stayed far back, hidden under trees, listening.

They didn’t announce Patton was missing. They didn’t broadcast his last call. They didn’t tell the infantry—because frightened troops fought like cornered animals.

Instead, Eisenhower ordered a message sent to Third Army headquarters, coded and short:

Maintain normal operations. No deviation. Await instructions.

Patton’s staff, loyal and furious, understood what it meant: Keep your mouths shut, or you’ll make this worse.

Hours passed. Snow began to fall, softening the mud, hiding tracks. That worried Eisenhower more than artillery.

At 0415, a recon team found the first clue: a snapped antenna near a ditch line, bent like someone had stepped on it in anger.

At 0450, they found tire marks that didn’t match Patton’s vehicles—wider, heavier, suggesting a truck.

At 0530, they found a piece of fabric snagged on barbed wire: a strip of starched khaki with a faint, grimy outline where a patch had been ripped off.

And at 0610, they found a radio handset smashed in half, tossed into a shallow stream as if someone wanted it to disappear.

Major Thomas Hargreaves, leading the recon, stared at the broken handset and felt his stomach tighten.

“This wasn’t equipment failure,” he muttered.

His sergeant nodded. “No, sir. This was… deliberate.”

They followed the tire marks until they reached a crossroads where multiple convoys had churned the ground into a soup of tracks and confusion. The trail vanished there, swallowed by the war’s mess.

Hargreaves radioed back. “We lost the line. Too many vehicles.”

The voice that answered wasn’t a junior operator.

It was Eisenhower himself.

“Then don’t chase tracks,” Eisenhower said. “Chase intent.”

Hargreaves hesitated. “Sir?”

Eisenhower’s voice came through calm, almost gentle. “Whoever did this had a destination,” he said. “Find the place that makes sense for someone who wants Patton alive for a few hours—and quiet.”

Alive.

The word mattered.

Hargreaves understood. If Patton were dead, they would’ve left him where he fell. But silence suggested leverage. Threat. Bargain.

He looked at his map and began thinking like a criminal instead of a soldier.

Where would someone hide a general?

Not in town. Too many eyes.

Not in a German outpost. Too risky.

Somewhere close enough to reach quickly, but isolated enough to control.

A farm. A barn. A cellar. A ruined mill.

Hargreaves turned his jeep toward a cluster of abandoned structures marked on the map as an old cider press.

In Eisenhower’s tent, the hours tightened into a rope.

Bedell Smith watched Eisenhower read and reread reports, his finger tapping the same point on the map like a metronome.

“Sir,” Bedell Smith said carefully, “if this turns into a scandal—”

Eisenhower cut him off without looking up. “If it turns into a scandal, it means we didn’t stop it soon enough,” he said. “And if we don’t stop it, scandal will be the least of our problems.”

Bedell Smith sighed. “You’re thinking this is theft and corruption.”

Eisenhower’s gaze lifted. “I’m thinking it’s fear,” he said.

“Fear of what?”

Eisenhower’s jaw tightened. “Fear of exposure. Fear of Patton’s appetite for confrontation.”

Bedell Smith frowned. “Patton’s not subtle.”

“No,” Eisenhower said, “and that’s why he’s useful. He walks into rooms other men avoid. He says things other men swallow.”

Bedell Smith hesitated. “And you think that got him taken.”

Eisenhower leaned back, finally letting the exhaustion show for just a second in the lines around his eyes.

“I think,” he said slowly, “that Patton has been making enemies in places we pretended didn’t exist.”

He reached for the radio microphone again, as if he could call Patton back through sheer will.

He didn’t speak into it.

Instead, he said to Bedell Smith, low enough that only the closest men heard:

“When George talks, he makes problems visible.”

Bedell Smith murmured, “And someone wanted the problem invisible.”

Eisenhower nodded once. “Yes.”

Then he spoke the phrase that became the tent’s private oath, the words that stiffened spines and focused minds:

“Find him before the silence becomes a story.”

At 0730, Major Hargreaves reached the abandoned cider press.

It sat in a shallow hollow, half-collapsed, roof sagging, door hanging loose. The snow had started to stick now, whitening the ground like a clean sheet trying to cover blood.

Hargreaves signaled his men forward. No shouting. No heroics.

They approached from three angles.

Inside, the air smelled of rot and old apples.

A low voice came from the darkness—irritated, unmistakably American, unmistakably furious.

“If that’s you, Hargreaves,” it growled, “you’re late.”

Hargreaves froze, then exhaled so hard it hurt.

“General?” he whispered.

Patton stepped into the weak light.

He was bruised. His helmet was gone. His uniform was stained with mud and something darker. His hands were bound with rope that had left angry red marks around his wrists.

But his eyes were alive—blazing with the kind of rage that could power an army.

Hargreaves rushed forward and cut the rope.

Patton flexed his hands like a man testing the world again.

“Sir,” Hargreaves said, voice shaking with relief, “we—”

Patton grabbed him by the collar—not in anger, but urgency.

“Listen,” Patton hissed. “This wasn’t Germans. You hear me? It wasn’t Germans.”

Hargreaves nodded rapidly. “Who was it, sir?”

Patton’s jaw clenched. “Men in our uniforms,” he said. “They didn’t want me dead. They wanted me quiet.”

Hargreaves swallowed. “Why?”

Patton’s eyes narrowed. “Because I found something,” he said. “Something rotten. Fuel gone. Food gone. Records forged. And I started asking questions where questions aren’t welcome.”

Hargreaves felt the cold deepen. “Did you see their insignia?”

Patton’s mouth curled in disgust. “They’d ripped patches off,” he said. “But one of them had an MP whistle. Another had a ring like he’d never missed a meal.”

Hargreaves asked, “Where did they go?”

Patton’s gaze flicked to the door. “South,” he said. “And they’ll be warned by now.”

Hargreaves started to speak, but Patton cut him off.

“Get me Ike,” Patton demanded. “Now.”

Eisenhower met Patton in a small room with a single stove and two chairs.

No staff. No photographers. Only Bedell Smith stood near the door, arms crossed, face grim.

Patton walked in stiffly, bruises dark against his skin, but his posture unbent.

Eisenhower rose. He didn’t salute. He didn’t smile.

He simply looked at Patton as if checking the world had returned to balance.

Patton broke the silence first. “You got my last message?”

Eisenhower nodded. “I got half,” he said.

Patton’s mouth twisted. “I was going to tell you I’d found wolves wearing our coats.”

Eisenhower’s eyes sharpened. “Tell me everything.”

Patton did. Not dramatized. Not embellished. Just hard facts—roadside stop, men appearing fast, radio smashed, threats spoken in plain American accents.

“They told me to stop digging,” Patton said, voice low. “They said if I didn’t, you’d have trouble you couldn’t control.”

Bedell Smith’s jaw clenched.

Eisenhower’s face stayed composed, but his voice dropped to something colder.

“What did you say back?” Eisenhower asked.

Patton’s eyes flashed. “I told them they’d picked the wrong man to muzzle,” he growled.

A silence stretched.

Then Eisenhower spoke—quietly, steadily, as if the words had been waiting in him since the radio went dead.

“When your message went silent,” Eisenhower said, “I said one thing out loud, and one thing to myself.”

Patton narrowed his eyes. “What?”

Eisenhower held his gaze.

“Out loud,” Eisenhower said, “I said: ‘Find him.’”

Patton’s mouth twitched, almost approving.

“And to myself,” Eisenhower continued, voice barely above the stove’s soft crackle, “I said: ‘If George Patton can be taken inside our own lines, then any of us can.’”

Bedell Smith’s expression tightened.

Patton stared at Eisenhower, and for the first time since walking in, the fury in his eyes shifted into something else—recognition.

Eisenhower leaned forward slightly.

“George,” he said, “this war will be won on more than battlefields. It will be won on whether we keep our own house from collapsing.”

Patton’s jaw worked. “So what do we do?”

Eisenhower’s eyes hardened. “We cut the rot,” he said. “Quietly. Completely.”

Patton gave a slow, dangerous smile. “Finally,” he murmured.

Eisenhower didn’t smile back.

“This isn’t revenge,” Eisenhower said. “It’s survival.”

Patton nodded once. “Then let’s survive.”

Outside, the snow kept falling—covering tracks, hiding scars, softening the world.

But inside that room, two men understood something the history books would only hint at:

Silence wasn’t always caused by distance.

Sometimes, silence was engineered.

And when the most aggressive voice in the Allied Army suddenly vanished, Eisenhower’s quiet words weren’t panic.

They were a verdict.

THE END