When Berlin Learned Churchill Was Secretly Heading to Washington, Hitler Didn’t Celebrate—He Delivered One Cold Verdict That Made His Inner Circle Realize the War Had Just Changed Forever.

1) The Message That Arrived Without Footsteps

The radio room beneath the government quarter didn’t feel underground. It felt sealed—like a jar tightened until even courage couldn’t breathe.

Otto Keller sat at a battered desk with a headset pressed to his ear, translating fragments that arrived like broken glass: call signs, weather chatter, clipped naval shorthand. He wasn’t a sailor and wasn’t meant to be. He was a language man—trained to pull meaning from noise, trained to stay invisible while history spoke in codes.

That morning in December 1941, Berlin’s sky was the color of metal filings. Winter pressed hard against every window. Otto had been awake too long when the operator across from him straightened and mouthed a single word:

“Atlantic.”

Otto lifted his pen.

Signals had been coming in fast since the Pacific shock a few days earlier—everyone suddenly shouting at once, each desk trying to prove it mattered. But this one came in oddly measured, like the sender had taken a breath before speaking.

The operator slid the transcription over.

Otto read it once, then again, slower.

A secure movement. A guarded itinerary. A ship name that didn’t belong to a rumor.

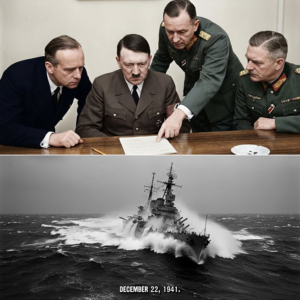

HMS Duke of York.

A destination that made Otto’s pen hover above the paper like it was afraid to commit.

Washington.

Otto felt his pulse in his throat.

It wasn’t that Otto didn’t know the British leader traveled. He did. People like that moved through the world the way storms moved—loudly, inevitably, rearranging everything. But this message wasn’t only travel.

It was timing.

A British prime minister sailing across the Atlantic in secret, arriving in the American capital, right as the world snapped wider into something global. (Churchill did travel to Washington in late December 1941 after a secret crossing, and the Arcadia Conference followed.) Wikipedia+1

Otto turned to his superior, Captain Frisch, and kept his voice flat.

“Sir,” Otto said, “this goes upstairs.”

Frisch’s eyes narrowed, took in the paper, and then—just for a heartbeat—showed the smallest flicker of worry.

“Typed copy,” Frisch ordered. “Two versions. One clean, one detailed.”

Otto’s fingers moved faster than his thoughts. He typed, corrected, retyped. Each letter felt heavier than the last, as if the keys were stamping consequences onto the page.

When he finished, Frisch placed the document into a folder so plain it looked harmless.

Then he said, almost quietly, “You’re coming.”

Otto’s mouth went dry. “Me?”

Frisch nodded. “You translated it. If questions come, you answer them.”

Otto stood, smoothed his coat, and followed.

They moved through corridors where the air smelled like damp wool and urgency. Boots echoed on stone. Doors opened and closed without chatter, as if everyone had agreed words were too expensive.

At the first checkpoint, an officer read the folder’s cover and waved them through without a joke.

At the second checkpoint, the guard didn’t wave.

He stared at the word Washington as if it had teeth.

Then he stepped aside.

Otto’s heart beat harder.

Upstairs, somewhere beyond these walls, important men would decide whether this message was merely interesting—or fatal.

2) The Waiting Room of Power

The antechamber outside the private meeting room was warm enough to be unsettling. Otto had learned that warmth was often a warning in places like this. Warmth meant someone expected to stay awhile.

A secretary with a tight face took the folder and disappeared through a door. Otto and Frisch were left standing beneath a painting Otto never dared to look at for too long.

Minutes passed.

Otto’s mind filled the silence with questions.

Why now? Why Washington? Was it ceremonial, or was it a steering wheel being grabbed with both hands?

The British leader’s presence in Washington meant more than speeches and handshakes. It meant planning—shared lists, shared priorities, shared maps. The kind of coordination that made oceans feel smaller. nationalww2museum.org+1

A door opened.

A different aide appeared—older, eyes trained to erase emotion. He glanced at Otto’s face and seemed to decide Otto was safe to ignore.

“Inside,” the aide said to Frisch. His gaze flicked to Otto. “And him.”

Otto walked in and immediately felt the room’s gravity.

There was a long table. A large map board at the far end. A few men in uniforms, a few in civilian suits. Not many. The kind of meeting that didn’t want witnesses.

And at the center—still as a post, hands behind his back—stood the man Otto had only seen at a distance.

Otto kept his eyes down, as protocol demanded.

But you could feel a person like that without looking. Like you could feel a furnace across a room.

Frisch stepped forward, spoke the formal introduction, and offered the folder.

A gloved hand took it.

The room seemed to hold its breath while pages were read.

Otto heard the soft sound of paper shifting, the faint scrape of a chair leg, the barely-there cough of someone trying not to exist.

Then a voice—flat, controlled, carrying authority like a blade—broke the quiet.

“Read it,” the voice said.

Frisch replied quickly, “It concerns the British prime minister’s transit, my Führ—”

“Read,” the voice repeated.

Otto’s throat tightened. Frisch began.

He read the key lines: the ship, the secrecy, the destination, the arrival window.

The moment Frisch said “Washington,” the room changed. Otto could feel it. Like the temperature dropped one degree, not in the air but in the confidence of the men listening.

For a heartbeat, there was silence.

Then the voice spoke again, calm in a way that was worse than shouting.

“So,” the voice said, “he’s going to the White House.”

No one responded.

Otto stared at the edge of the map table.

He couldn’t help imagining the scene across the Atlantic: Churchill arriving in Washington after the secret crossing, stepping into rooms filled with American flags and bright lights, talking strategy while the ink was still wet on global war. Wikipedia+1

And here—Berlin, dim, closed, echoing.

The voice continued, and this time the room leaned in without moving.

“Britain doesn’t travel for comfort,” the voice said. “Britain travels for leverage.”

A man in uniform cleared his throat. “It could be symbolic, sir. A show of—”

The voice cut him off, not harshly, but with a precision that made the interruption look childish.

“No,” the voice said. “It’s a workshop meeting.”

Otto felt his scalp tighten.

A workshop meeting.

Not diplomacy—manufacturing.

Then the voice delivered the line Otto would remember long after the war ended and the buildings around him changed names.

It wasn’t theatrical. It wasn’t a speech.

It was a verdict.

“When Churchill reaches Washington,” the voice said, “the ocean stops being a moat.”

The words landed like a weight.

Otto’s fingers twitched, wanting to write it down, but he didn’t dare. He didn’t have permission. And he didn’t want to be caught preserving something that sounded too honest.

The voice went on, quieter now, almost conversational, which somehow made it worse.

“They will make one schedule,” the voice said. “One list. One rhythm. And once they share a rhythm, they share a machine.”

Otto sensed a ripple of unease. Men shifted slightly, as if the chairs had become uncomfortable.

A civilian adviser spoke carefully. “Sir, if this meeting becomes a formal combined direction—”

“It will,” the voice replied.

That certainty chilled Otto more than anger would have.

Then the voice added something that wasn’t a quote Otto had ever read in a newspaper. It sounded too human for that. It sounded like the speaker had simply noticed an uncomfortable truth.

“And the British leader,” the voice said, “will do what he does best.”

A pause.

“He will push them toward us.”

Otto’s heart thudded once.

Push them toward us.

A senior officer tried to recover the room’s posture with practicality. “We can respond with a naval emphasis. Increased—”

The voice cut in again, still calm.

“You can’t stop two men with one plan,” the voice said. “You can only hope they quarrel.”

Otto could almost hear the unspoken fear behind that sentence.

Because if Washington and London stopped quarreling—if they planned like one—then the war’s shape changed. That was the real danger of Churchill arriving there: not the visit itself, but what it symbolized and enabled—coordination at the top. nationalww2museum.org+1

Otto stood frozen, still pretending to be wallpaper.

Then the voice turned slightly, and Otto felt it—attention moving.

“Translator,” the voice said.

Otto’s stomach dropped.

“Yes, sir,” Otto managed.

“How certain is this?”

Otto swallowed. His instincts screamed to sound confident. His survival screamed to sound useful.

“It’s consistent with multiple intercept fragments,” Otto said carefully. “And with the ship identification. The route appears deliberate and concealed.”

A beat.

“And the date range?”

Otto recited what he had translated.

The voice was silent a moment longer.

Then, almost softly, it said, “He wants to arrive while the new fire is still hot.”

Otto didn’t breathe.

The room understood what that meant without explanation: right after the shock, while decisions were still fluid, while fear could be shaped into policy.

Then the voice ended the discussion with a sentence so final it felt like the meeting had been closed by force.

“Let them meet,” it said. “But don’t mistake it for a visit.”

The voice’s tone hardened just slightly.

“It’s a joining.”

3) The Man in the Hallway

Afterward, Otto and Frisch were dismissed without ceremony. No one thanked them. In a place like that, being thanked meant you had been noticed, and being noticed could be dangerous.

In the hallway, Otto finally let himself inhale.

Frisch’s face was pale. “You heard that,” Frisch muttered.

Otto nodded, still feeling the sentence in his bones: the ocean stops being a moat.

They walked quickly.

But as they reached the antechamber, the older aide who had ushered them in appeared again.

He held out a slip of paper.

“Orders,” the aide said to Frisch, then glanced at Otto.

“And for you,” he added, “a warning.”

Otto’s throat tightened. “A warning?”

The aide’s eyes were tired. “What you heard in that room,” he said quietly, “you didn’t hear.”

Otto nodded. “Yes.”

The aide studied Otto’s face, as if trying to decide if Otto understood what “yes” meant.

Then the aide said something that didn’t sound like a threat. It sounded like weary truth.

“History is made twice,” the aide murmured. “Once by men who speak. Once by men who repeat.”

He walked away.

Otto stood still for a moment, feeling the hallway tilt.

Frisch tugged Otto’s sleeve. “Move,” he hissed.

They moved.

Downstairs again, back into the radio room’s cold, back into the clacking machines, back into a world where words were turned into paper and paper into orders.

But Otto couldn’t stop thinking about Washington.

About Churchill stepping into rooms where American planners waited with maps. About the Arcadia Conference that soon followed in Washington, where strategies were aligned and priorities set. Wikipedia+1

Otto understood now why that line had frozen the room.

Because war wasn’t only fought with weapons.

War was fought with calendars.

With agreements.

With who met whom, and when, and what they promised to do together.

And the moment Churchill went to Washington, someone in Berlin had realized the world’s most dangerous thing wasn’t a single enemy.

It was an alliance that stopped improvising and started coordinating.

4) The Sentence Otto Couldn’t Bury

That night, Otto sat in his small room with the curtains drawn and a pencil in his hand.

He should have slept.

Instead, he found himself writing a letter he would never send.

Dear Leni, he began, addressing his sister in a town that had become quieter each week.

Then he stopped.

He couldn’t write about politics. He couldn’t write about meetings. He couldn’t write about the voice.

But he could write about a feeling.

So he wrote:

Today I learned that travel can be a weapon.

He stared at the line until the pencil shook slightly between his fingers.

Because he knew the real shock wasn’t what the British leader would say in Washington. Otto didn’t know that, and the newspapers would only show smiles and speeches.

The shock was what the Berlin leader had understood instantly—and said aloud.

That this was a joining.

A shared rhythm.

And that once two nations shared a rhythm, they could move like one machine.

Otto tore the letter into pieces and burned it in the tiny stove, watching the words curl and vanish.

The next morning, the radio room filled with more messages, more chatter, more fragments.

But Otto listened differently now.

Every mention of Washington felt heavier.

Every mention of the Atlantic felt smaller.

And whenever Otto heard the clack of the teleprinter, he remembered the sentence he wasn’t allowed to remember:

The ocean stops being a moat.

Because in that one cold verdict—spoken in a room built for certainty—Otto had heard something close to fear.

Not fear of a ship.

Not fear of a speech.

Fear of two leaders in one city, drawing one plan, and turning retreat and defense and patience into something coordinated—something that didn’t need luck.

A joined machine.

And Otto, the invisible translator, understood then that some sentences didn’t need to be shouted to change the course of a war.

They only needed to be true.