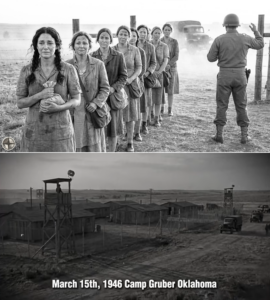

They Were Told “You Don’t Belong Here”—But the German Women in a Quiet American War Camp Discovered a Secret That Made Them Beg to Never Leave

The first time Anneliese heard the sentence, it didn’t sound like anger.

It sounded like a rule that had existed long before she had.

“You don’t belong here,” the American said, not loudly, not cruelly—just certain, like he was reading weather off the sky.

He stood at the gate with a clipboard tucked under one arm, a cap low on his forehead, and a pair of boots so clean they looked borrowed. Behind him was a fence line that ran like a stitched seam across the prairie. Beyond the fence: pecan trees, red dirt, and a road that disappeared into heat.

Anneliese did not answer. She kept her face steady the way she had learned to do when men with uniforms spoke in sentences that sounded final.

But the words stuck anyway.

You don’t belong here.

The camp—Camp Marigold, the sign said—sat outside a small American town that could have been any town. A water tower in the distance. A church steeple like a finger pointing upward. A diner that smelled like frying oil and coffee.

Inside the camp there were wooden barracks, laundry lines, and the steady clack of a kitchen door that never seemed to rest. There were rules posted in neat letters. There were schedules. There were ration lists. There were inspections that happened at the same time every week, like the world might break if the ritual changed.

For months, Anneliese had told herself that predictability was mercy.

She had also told herself that mercy never lasted.

She was wrong about one of those things.

On the day the sentence arrived, she was carrying a bucket of peelings behind the kitchen, heading for the compost pit. The summer sun lay on her shoulders like a hand that refused to lift. The air buzzed with insects. Somewhere in the distance, a radio—kept low by an unseen guard—played a song that sounded too cheerful for any place made of fences.

Her friend Greta called after her.

“Anna! Wait!”

Greta’s cheeks were smudged with flour. Her hair, always escaping its pins, was stuck to her forehead. She was laughing as she ran, laughing like the camp hadn’t taken anything from her at all. It was a kind of defiance Anneliese admired but couldn’t copy.

Greta caught up and leaned over the bucket, peering inside.

“Peelings,” she said, as if announcing a grand discovery. “The glamorous life.”

“It’s better than scrubbing pots,” Anneliese replied.

Greta grinned. “Nothing is better than scrubbing pots.”

Anneliese gave her a look.

Greta’s grin softened. “You’re thinking again.”

“I’m always thinking.”

“That’s the problem.”

Greta nudged her shoulder. “Come on. Walk with me. The mail is supposed to arrive.”

Anneliese’s hands tightened on the bucket handle. “Mail.”

Greta said the word like a prayer. Some of the women had received letters—thin, fragile things that arrived weeks late and smelled faintly of smoke. Others received nothing. Some had stopped asking.

Anneliese had received one postcard months ago. Two sentences. No name, no return address. Just a brief note that could have been written by anyone with a steady hand:

Alive. Don’t come back yet. Wait.

She had read it so many times the paper had softened at the creases.

They reached the administrative building where the mail table sat under a fan that squeaked with every slow turn. A small crowd had already formed—women in plain camp dresses, their shoulders drawn tight, their eyes too hungry for paper.

A man behind the table sorted envelopes. He was older than most of the guards, with hair that had turned mostly gray. He wore his authority lightly, like a jacket he didn’t want to wrinkle.

Sergeant Halvorsen, they called him. He spoke carefully, as if every word could be a misstep.

He looked up when Anneliese arrived, then back down at his stack.

“Name?” he asked.

“Anneliese Koch,” she said.

He flipped through the envelopes once, then again, then set the stack down.

“Nothing today,” he said gently.

Greta’s name was next. She got an envelope. She held it to her chest with both hands, her smile trembling like a candle.

Anneliese felt something in her stomach twist—not envy, not exactly, but a sharp awareness of how thin hope could be.

Greta noticed her face.

“Next time,” Greta whispered.

Anneliese nodded as if that meant anything.

As they turned away, they heard Halvorsen clear his throat.

“Ladies,” he called. “There’ll be an announcement at assembly. This afternoon. Don’t be late.”

The crowd stilled. A quiet passed through it, heavy and sudden. It wasn’t fear of punishment—it was fear of news. News had a way of reshaping people. News could pull you apart without ever touching you.

Greta clutched her letter and said, “Let’s read it later.”

“Why?” Anneliese asked.

Greta’s eyes flicked toward the administrative building, toward the closed door that led inside.

“Because the camp is holding its breath,” Greta said. “And I don’t want to inhale at the wrong time.”

That afternoon, the women lined up in the assembly yard under the bleached sky. The fence threw thin shadows on the ground like prison bars made of light. A flagpole stood at the center. A breeze moved the flag lazily, as if even the wind was tired.

The camp commander—a captain with a sharp jaw and a voice that carried—stood on the wooden platform with Sergeant Halvorsen and a younger soldier Anneliese recognized as Corporal Mason. Mason had been at the gate earlier. He had said the sentence.

You don’t belong here.

Mason looked uncomfortable in the sunlight, shifting his weight from foot to foot. Halvorsen stood still as stone.

The captain began without greeting.

“An order has been received,” he said. “Transportation is being arranged. In the coming weeks, many of you will be relocated.”

A ripple moved through the crowd.

Relocated. The word was polite and smooth, like a stone rubbed until it no longer cut.

Greta’s hand found Anneliese’s. Her fingers were cold despite the heat.

The captain continued. “This camp was never intended to be permanent. The war is over. Arrangements are being made for return to your home country.”

The crowd erupted—not loud, not chaotic, but with a hundred small sounds at once: breath catching, murmurs, whispers that turned into questions.

Anneliese heard her own voice rise before she meant it to.

“Return?” she said.

The captain’s gaze found her. “Yes. Return.”

“Where?” someone else demanded.

“Across the ocean,” the captain answered, as if the ocean were a hallway. “Where you came from.”

A woman near the front shook her head so hard her hairpins fell out. “There is nothing there,” she said.

The captain’s expression hardened. “That is not for us to decide.”

And then Corporal Mason spoke, surprising even himself.

“You don’t belong here,” he said, the words landing like a stamp.

The crowd quieted.

Anneliese stared at him. His face looked younger up close, like someone who still hadn’t decided what kind of man he wanted to be. His eyes flicked to Halvorsen, then back to the women.

“You don’t belong here,” Mason repeated, softer. “This place… it’s temporary.”

Greta’s grip tightened.

Anneliese’s mind moved faster than her body. She pictured the ocean like a dark sheet. She pictured a city she barely recognized. She pictured rubble. Hunger. Strangers wearing familiar faces. She pictured the postcard: Don’t come back yet. Wait.

But there would be no waiting if they put her on a ship.

Something else flickered in her mind too—something she had noticed but never named. Camp Marigold was not cruel in the way she had expected cruelty to be. It was not kind, either. It was simply… stable.

A schedule. Meals. A bed. Work that ended when the sun went down. Guards who did not look away when you spoke. A fence that kept you in, yes—but also kept some things out.

And then there was the strange, quiet secret she had begun to suspect.

It wasn’t written anywhere. It wasn’t announced at assembly.

But it lived in the gaps between rules.

In the way Sergeant Halvorsen sometimes let the women linger near the library shelf after hours.

In the way the cook—Mrs. Daugherty, a woman with strong arms and a sharper tongue—slid extra biscuits onto plates when no one was watching.

In the way the town pastor had once stood outside the fence and read aloud from a book, as if the women inside had never heard stories.

In the way Camp Marigold had become, impossibly, a place where survival didn’t have to be earned every minute.

Anneliese realized she had started to believe in that.

And believing made the captain’s words feel like a personal betrayal.

“Is there a choice?” Anneliese asked, her voice steadier than she felt.

The captain’s mouth tightened. “No.”

Greta whispered, “There is always a choice.”

Anneliese turned her head slightly. “Not for us.”

Greta lifted her letter, still unopened. “Maybe for someone.”

That night, the barracks felt smaller than usual. The women moved like ghosts—folding blankets, packing and unpacking the same items as if repetition could change the outcome.

Greta sat on her bunk with her letter in her lap. Anneliese sat opposite, watching her.

“Open it,” Anneliese said.

Greta shook her head. “Not yet.”

“Why not?”

Greta’s eyes glistened. “Because once I read it, I’ll know what I’m losing.”

Anneliese swallowed. “You might be gaining something.”

Greta let out a breath that sounded like a laugh and a sob at once. “Anna, we are not the kind of people who gain things anymore.”

Silence stretched.

From outside, the camp’s generator hummed. Somewhere, a guard’s footsteps passed, steady and unhurried. The night air smelled of grass and dust and something sweet—honeysuckle, maybe.

Anneliese stood. “Come with me.”

Greta looked up. “Where?”

“Walk,” Anneliese said.

They slipped out into the yard, careful not to draw attention. The moon was bright enough to make the fence shine like wire stitched with light. They headed toward the far corner where the shadow of a pecan tree fell over the ground.

That was where Anneliese had discovered the secret weeks earlier.

Not by digging. Not by spying. By accident.

A small board behind the supply shed had come loose. Under it, a narrow space, and inside that space: a tin box wrapped in oilcloth. She had nearly put it back untouched.

But then she had heard footsteps and shoved it into her dress without thinking.

Later, alone, she had unwrapped it.

Inside were papers.

Not camp documents. Not ration lists.

Petitions.

Typed, neat, and careful. Names at the bottom—American names, some German names. Dates. Statements about employment, housing, sponsorship. Words like “placement” and “work program” and “community support.”

It was not a promise of freedom.

But it was proof of possibility.

Someone—maybe Halvorsen, maybe someone in town—had been preparing an alternate path for some of the women. A way to keep a few from being sent back immediately. A way to let them work, live, stay.

Anneliese had hidden the tin box again afterward, heart pounding, afraid she had imagined what it meant.

Now, under the pecan tree, she knelt and pried the loose board up with her fingers.

Greta hissed softly. “What are you doing?”

“Trust me,” Anneliese whispered.

She pulled the oilcloth-wrapped tin free and handed it to Greta.

Greta stared at it as if it were a bomb. “Anna…”

“Open it.”

Greta’s hands trembled as she peeled back the oilcloth. Moonlight caught the edge of the papers.

Greta read the first page, her lips moving silently.

Then she read a second.

Then a third.

Her eyes lifted slowly to Anneliese.

“This is…” Greta began.

“A door,” Anneliese said.

Greta’s voice cracked. “For who?”

Anneliese swallowed. “For those who can convince them.”

Greta clutched the papers to her chest, the same way she had clutched her letter. “Who made these?”

Anneliese shook her head. “I don’t know.”

Greta whispered, “Maybe… it’s for a few only.”

Anneliese’s jaw tightened. “Then we make it for more.”

Greta’s gaze darted to the fence line, to the dark shape of the guard tower.

“Anna,” she said, urgent. “If they find this on us—”

“I’m not asking you to carry it,” Anneliese replied. “I’m asking you to read it. To understand what it means.”

Greta looked down again. Her breathing sped up.

Then she said quietly, “This is why they keep telling us we don’t belong.”

Anneliese nodded. “Because if we belong even a little, the fence becomes something else.”

Greta’s eyes shone with sudden anger. “A lie.”

Anneliese thought of the captain’s voice: That is not for us to decide.

She thought of Mason at the gate, looking like a man reciting a rule he didn’t fully believe.

“No,” Anneliese said. “Not a lie. A fear.”

Greta exhaled. “What do we do?”

Anneliese stared at the papers until the words blurred.

Then she said, “We ask to stay.”

Greta’s voice was barely audible. “They’ll laugh.”

“Then we don’t ask once,” Anneliese said. “We ask again. We ask with names. With signatures. With proof we can work and not disappear into the shadows.”

Greta shook her head, tears slipping free now. “They’ll say no.”

Anneliese’s throat tightened. “Maybe. But if we’re going to be pushed onto a ship, I want them to remember our faces when they do it.”

Greta’s hands tightened around the papers. “We’ll need allies.”

Anneliese thought of Mrs. Daugherty sliding biscuits onto plates.

She thought of the pastor reading aloud.

She thought of Sergeant Halvorsen’s careful voice.

She thought—unexpectedly—of Corporal Mason, saying the sentence like it hurt his mouth.

“Yes,” Anneliese said. “We will.”

The next morning, Anneliese waited near the kitchen until Mrs. Daugherty came out with her apron tied tight and her hair wrapped in a scarf.

Mrs. Daugherty stopped when she saw Anneliese.

“You’re early,” she said.

“I need to talk,” Anneliese replied.

Mrs. Daugherty’s eyes narrowed. “About what?”

Anneliese kept her voice low. “About staying.”

Mrs. Daugherty’s mouth tightened as if she had bitten into something sour.

“You girls heard the captain,” she said.

“I heard him,” Anneliese replied. “I’m telling you he’s not the only voice that matters.”

Mrs. Daugherty’s gaze flicked left and right, checking for guards. “You better be careful,” she muttered.

Anneliese nodded. “I am careful. That’s why I’m here.”

Mrs. Daugherty studied her a long moment.

Then she said, quietly, “Meet me behind the pantry after lunch.”

Anneliese’s heart jumped.

“Why?” she asked.

Mrs. Daugherty’s eyes hardened. “Because you’re not the first to beg. And you won’t be the last.”

She walked away, leaving Anneliese standing in the dust with a hope so sharp it almost felt like pain.

That afternoon, behind the pantry, Mrs. Daugherty handed Anneliese a folded paper.

“Names,” she said. “People in town. Folks who’d take on workers. Folks who’d vouch.”

Anneliese stared. “Why are you helping?”

Mrs. Daugherty’s jaw clenched. “Because I’ve watched you girls work. Because I’ve watched you share what little you’ve got. Because my boy didn’t come home and I’m tired of the world acting like that means everybody’s got to suffer forever.”

Anneliese’s eyes stung.

Mrs. Daugherty pointed a finger at her. “But listen to me. This won’t be easy. The camp has rules. The government has rules. And people have opinions.”

Anneliese nodded. “I understand.”

Mrs. Daugherty’s voice softened, just a fraction. “Do you?”

Anneliese thought of the ocean.

“Yes,” she said. “But I also understand this: if we go back now, some of us won’t make it.”

Mrs. Daugherty looked away. “Then move fast,” she said. “And don’t do anything foolish.”

Anneliese almost laughed. She had never felt less foolish in her life.

By the end of the week, the barracks had changed.

Not outwardly—the bunks were still aligned, the blankets still folded, the floors still swept. But the women moved with a new purpose, like people who had spotted a crack in a wall and decided to pry it open with their bare hands.

They wrote letters.

They gathered signatures.

They rehearsed what they would say, what they would not say, how to sound grateful without sounding small.

Greta finally opened her letter.

It was from her sister.

Two pages, written in tight, hurried lines. The home they had known was gone. The town was crowded with displaced families. Food was scarce. Winter would be hard.

And then, at the bottom, a sentence that made Greta press her fist to her mouth:

If you have a chance to stay where you are safe, take it. Please. For both of us.

Greta showed Anneliese the letter with shaking hands.

Anneliese read it once, then again.

Then she looked up. “We are doing the right thing.”

Greta nodded, tears spilling freely now. “We are doing something.”

When the day came, they stood again in the assembly yard, but this time they were not waiting for an announcement.

They were holding papers.

The captain stepped onto the platform, ready to speak.

But before he could, Anneliese took one step forward.

Her knees shook. Her mouth felt dry. She heard her own heartbeat like a drum.

“Captain,” she said.

The captain’s eyes narrowed. “Koch.”

“I request permission to speak.”

A murmur ran through the women.

The captain’s jaw tightened. “This is not—”

Sergeant Halvorsen cleared his throat.

The captain paused, irritated. Halvorsen’s face was careful, but his eyes were firm.

The captain exhaled sharply. “You have one minute.”

Anneliese lifted the papers.

“We ask to stay,” she said clearly. “Not forever under a fence. Not as a burden. We ask to work. To be placed with sponsors. We have names. We have offers. We have people willing to vouch.”

The captain stared at the papers as if they were an insult.

Corporal Mason’s eyes widened.

Anneliese went on, her voice gaining strength.

“You say we don’t belong here,” she said, looking directly at Mason now. “But we have followed your rules. We have done the work you asked. We have tried to be quiet and grateful and invisible.”

She swallowed.

“We are done being invisible.”

The yard was so silent that even the flag’s soft snapping sounded loud.

The captain’s voice came out tight. “These papers—where did you get them?”

Anneliese held them higher. “From people who know us. From people who have watched us. From people who believe we can belong somewhere, even if it is not here behind this fence.”

The captain’s eyes flicked to Halvorsen. “Sergeant.”

Halvorsen said evenly, “There are procedures for this, sir.”

The captain’s face reddened. “Procedures.”

Halvorsen didn’t flinch. “Yes, sir.”

Corporal Mason finally spoke, but not to the women—almost to himself.

“This isn’t how it’s supposed to go,” he murmured.

Anneliese heard him.

She met his eyes.

“Maybe that’s the point,” she said.

For a moment, Mason looked like he might argue.

Instead, he looked away.

They did not get an answer that day.

But they got something else—something Anneliese had not dared to expect.

They got time.

The ship lists were revised. The departures slowed. Meetings happened behind closed doors. Names were read aloud. Papers were stamped. More signatures arrived from town.

Some women were told no. Some were told to wait. Some were approved in small, careful batches, like the world could only handle mercy a spoonful at a time.

The camp began to feel like a place balancing on the edge of becoming something new.

And on the morning Anneliese was called to the administrative building, she walked there with her hands sweating and her shoulders square.

Inside, the fan squeaked overhead.

The captain sat behind the desk, looking tired.

Sergeant Halvorsen stood to one side.

Corporal Mason was there too, silent, his eyes on the floor.

The captain slid a paper across the desk.

“Temporary placement,” he said flatly. “With conditions. Work assignment. Regular check-ins. A sponsor in town.”

Anneliese stared at the paper as if it might vanish.

“You’re… allowing it?” she managed.

The captain’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile, not quite a grimace. “Don’t mistake this for sentiment.”

Anneliese lifted her eyes. “Then what is it?”

The captain tapped the paper. “It is paperwork. And it is not guaranteed to last.”

Anneliese nodded. “I understand.”

She signed where Halvorsen pointed.

Her hand shook, but her name came out legible.

When she finished, Halvorsen offered his hand.

It was a small gesture, almost nothing.

But it made Anneliese’s throat tighten.

She shook his hand.

Then she turned to leave.

At the door, Corporal Mason spoke.

“Hey,” he said.

Anneliese paused.

Mason cleared his throat, uncomfortable. “About what I said. At the gate.”

Anneliese waited.

He looked up finally, eyes searching her face. “I was told to say it,” he admitted.

“And do you believe it?” Anneliese asked.

Mason hesitated.

Then, quietly, “I believed it was easier.”

Anneliese nodded once.

“Easier for who?” she asked.

Mason didn’t answer.

Anneliese opened the door.

Before she stepped out, she said, “I don’t need you to tell me where I belong. I need you to understand what it costs when you decide I don’t.”

She left him standing there with his silence.

Outside, the sun was bright, the air warm.

Greta was waiting in the yard, eyes wide.

Anneliese held up the paper.

Greta’s hands flew to her mouth. Tears sprang instantly.

“Anna,” she whispered.

Anneliese walked to her and let Greta cling to her like a lifeline.

Around them, other women watched—some smiling, some crying, some too exhausted to react.

Not everyone would stay.

Not everyone would be approved.

But something had shifted.

The camp was no longer holding its breath.

It was exhaling.

That evening, under the pecan trees, Anneliese sat with Greta and watched the fence line glow in the fading light.

The fence was still there.

The rules were still there.

But now there was also a paper in her pocket that proved the sentence didn’t get to be the final word.

Greta leaned her head on Anneliese’s shoulder.

“Do you think we belong?” Greta asked.

Anneliese stared at the horizon where the sky met the prairie, where the world looked wide enough for more than one kind of ending.

“I think,” Anneliese said slowly, “that belonging isn’t something you’re given.”

Greta sniffed. “What is it, then?”

Anneliese smiled—small, real, and aching.

“It’s something you insist on,” she said. “Even when they tell you you don’t.”

And for the first time in a long time, the future didn’t feel like a door slamming shut.

It felt like a door—barely open—waiting for someone brave enough to step through.