“They Ran Out of Modern Guns—So Shipyard Women Unlocked a 19th-Century Cannon and Turned a Merchant Ship Into a Floating Argument”

The crate arrived with a museum label still nailed to the wood.

It was stenciled in careful, faded letters—PROPERTY OF CITY HISTORICAL COLLECTION—like the war had borrowed it on a promise it didn’t have time to keep. Four men with a forklift eased it onto the shipyard floor, and the moment the tires touched the concrete, every head in Bay Three turned.

Because the crate was the wrong shape.

Too long. Too stubborn. Too old-fashioned.

Mae Donnelly wiped her hands on her coveralls and stared as if she could will the past back into the box. Around her, welders paused mid-spark. Riveters lowered their hammers. Even the foreman—who never stopped moving unless something was on fire—stood still long enough to be caught in it.

“Tell me,” Mae said, “that’s not what I think it is.”

Ida Kline leaned in, reading the label like it might be a joke. “It’s exactly what you think it is.”

Gloria Reyes, smaller than both of them but quicker with her eyes, ran her fingers along the crate’s edge and frowned. “A cannon?”

“A cannon,” Ida confirmed, voice flat with disbelief.

Mae let out a short laugh that wasn’t laughter at all. “We’re building ships for the biggest war anyone’s ever seen, and they’ve sent us… a cannon.”

The foreman finally spoke. “Don’t start. It’s temporary.”

“Temporary is what they said about the missing steel,” Gloria muttered. “And the missing bolts. And the missing engines.”

Mae didn’t answer. She was watching the Navy lieutenant walking toward them from the office side—Lieutenant Caldwell, pressed uniform, neat hair, a clipboard held like a shield. Caldwell had the look of a man who believed chaos was a personal insult.

He stopped beside the crate and cleared his throat. “Ladies.”

Mae didn’t correct him. Not today. Not with that crate sitting there like a dare.

Caldwell tapped the clipboard. “This item is to be installed on Liberty Ship 441, effective immediately.”

Ida lifted an eyebrow. “Installed where?”

“On the stern mount,” Caldwell said, as if this were the most reasonable sentence in the world.

Mae stared at him. “You’re telling me the ship’s supposed to leave the yard with a museum piece bolted to her deck because the modern guns never arrived.”

Caldwell’s jaw tightened. “The scheduled armament is delayed.”

“So we’re improvising,” Mae said.

Caldwell’s eyes flicked to the crate, then back to her. “The ship is sailing. The ocean doesn’t wait for shipping manifests.”

Gloria crossed her arms. “Neither do raiders.”

For a moment, Caldwell looked as if he might pretend he hadn’t heard that. Then he said, quietly, “Exactly.”

That word—exactly—made the air in Bay Three feel colder.

Mae stepped closer to the crate. “What kind is it?”

Caldwell hesitated, then read from his notes. “Nineteenth-century naval smoothbore. Originally displayed as coastal defense heritage. Converted for ceremonial firing. We have an order to restore it to operational condition.”

Ida gave him a slow look. “Operational condition.”

Caldwell’s pen hovered above his clipboard. “It can fire.”

Mae said, “So can a slingshot.”

Caldwell’s expression tightened into something between irritation and worry. “You have forty-eight hours. You’ll receive ammunition allotment separately.”

Gloria’s voice sharpened. “You’re sending people into the Atlantic with an antique and calling it protection.”

Caldwell finally looked away. Not in shame—more like a man checking a door he knows is locked.

“It’s not protection,” he said. “It’s a message.”

“A message to who?” Mae asked.

Caldwell’s eyes returned to the crate. “To anyone who thinks a merchant ship is helpless.”

Mae felt the argument forming in her chest, big and ugly. The war had already rewritten rules about who worked where and who built what. Now it wanted to rewrite what counted as a weapon.

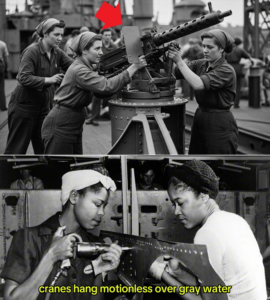

And it was asking them—women covered in grease and grit—to make the past dangerous again.

1) The Weapon Nobody Wanted to Talk About

They opened the crate that afternoon.

The wood came away in stubborn planks, nails squealing as if complaining on behalf of the thing inside. Underneath, wrapped in oilcloth and old pride, the cannon lay like a sleeping animal: thick barrel, iron dulled by time, a faint engraving near the muzzle that had once been decorative and now looked like a scar.

Ida whistled under her breath. “She’s heavy.”

Mae ran her hand over the barrel’s cold curve. “Heavy doesn’t mean useful.”

Gloria crouched and peered at the mounting points. “The trunnions are intact. If we can machine the fittings—”

Ida interrupted, “If we can machine the fittings in a shipyard that can’t even get enough new bolts to finish a hatch.”

Mae looked around Bay Three: half-finished deck plates, stacks of substitute steel, and men in the corner pretending not to stare at them. The whole yard was already a patchwork of shortages and stubbornness. The cannon was just the most honest symbol of it.

Caldwell returned with two sailors and a set of instructions that looked like someone had typed them while angry.

“Read it,” Ida said, taking the pages and scanning. Her face shifted from skepticism to something else. “This is ridiculous.”

Mae leaned in. “What?”

Ida pointed. “They want a liner inserted. They want the bore cleaned, the carriage adapted, and a firing mechanism rigged that doesn’t rely on ‘ceremonial procedures.’”

Gloria’s eyes narrowed. “So… they want it to actually work.”

Mae swallowed. “Work against what?”

Caldwell answered before anyone could stop him. “A surfaced submarine. A fast boat. Anything that comes too close.”

Ida snorted. “A surfaced submarine won’t politely sit there while we load a muzzle.”

Caldwell’s face tightened. “Then you’d better make it faster.”

The words landed like a slap, not because they were cruel, but because they were true.

Mae stared at the cannon again. The engraving caught the overhead light: an old crest, almost smug. It was the kind of thing that belonged on a pedestal, not on a deck about to cross a hostile ocean.

“Fine,” Mae said finally. “If the war wants a relic, we’ll give it one.”

Gloria looked up. “Mae—”

Mae’s voice lowered. “But we’re not making a museum showpiece. We’re making a tool. If this thing goes out there and fails, it won’t be the lieutenant’s career that takes the hit.”

Caldwell stiffened.

Mae met his eyes. “It’ll be someone’s return that never happens.”

Silence tightened the space between them. Caldwell didn’t argue—maybe because he had no argument that didn’t sound like paperwork.

He only said, “Then do it right.”

2) The Shipyard Became a Battlefield Without Leaving the Harbor

The next two days turned Bay Three into something sharper than a workplace.

They stripped the cannon down like surgeons. Ida handled the metalwork with grim precision, measuring and re-measuring until her pencil marks looked like bruises on the steel. Gloria took the mounting problem and attacked it like it had offended her personally—drafting brackets, adapting old patterns, arguing with machinists until they stopped dismissing her and started listening.

Mae, as always, became the point where decisions gathered. She didn’t call herself a leader, but the crew treated her like one, because leadership was often just the willingness to stand in front of a problem and refuse to move.

Rumors spread fast in a shipyard. By the second night, everyone knew.

“They’re putting a pirate cannon on a Liberty,” someone joked.

“Desperation,” someone else muttered.

“She’s going to blow her own deck clean off,” a welder warned.

A man named Haskins—older, bitter, and loud—walked past Mae’s station and said, without slowing, “Should’ve waited for real guns instead of playing hero.”

Mae didn’t look up from the fitting she was checking. “Real guns didn’t arrive,” she said.

Haskins snorted. “Then maybe the ship shouldn’t sail.”

Ida straightened, eyes sharp. “Tell that to the men waiting on cargo. Tell that to the crews already out there.”

Haskins shrugged, the gesture full of ugly comfort. “Not my problem.”

Mae finally stood and stepped toward him, slow and steady. “That’s the difference,” she said. “It’s not your problem until it is. And by then, it’s everyone’s.”

Haskins glared, then walked away, muttering.

Gloria watched him go. “He’s not wrong about one thing.”

Mae glanced at her.

Gloria nodded toward the cannon. “This is going to be controversial.”

Ida laughed once, humorless. “Everything about this war is controversial.”

Mae looked down the bay where the half-finished Liberty waited—big, blunt, built for carrying, not fighting. The Navy wanted her to have teeth, but the teeth were delayed, and the ocean wasn’t.

So the yard’s women were making teeth out of history.

3) The Test Fire That Split the Yard in Two

They tested it on the morning of the third day, with everyone pretending they weren’t watching.

The cannon sat on a temporary mount on the yard’s far apron, pointed safely toward the open water beyond the breakwater. The new brackets shone with fresh machining. The firing mechanism was improvised but sturdy—Gloria’s design, Ida’s build, Mae’s insistence that nothing be “good enough” if “good enough” could fail.

Caldwell stood off to the side with two sailors and a stiff posture.

Mae approached the cannon and ran a hand along the barrel one last time. “You ready?”

Gloria swallowed. “As ready as anyone can be for a century-old argument with physics.”

Ida checked the breech rigging—adapted, not truly breech-loading, but enough to speed the process. “If it backfires, I’m haunting both of you.”

Mae gave her a look. “If it backfires, we’ll be too busy to haunt anybody.”

The sailors loaded with careful motions, their faces tight. The powder bag looked absurdly small for the cannon’s mouth, but Caldwell insisted on the allotment—limited supply, controlled risk, maximum intimidation.

“Stand clear,” Caldwell called.

Mae stepped back with Ida and Gloria, hearts thudding in sync.

A yard whistle blew somewhere. A gull screamed overhead.

Then the cannon fired.

The sound wasn’t the sharp crack of modern weapons. It was a deep, chest-thumping boom that rolled across the harbor like a storm choosing a direction. Smoke burst from the muzzle in a thick white cloud, drifting slow and proud. The recoil jolted the mount hard—but it held.

A moment later, a splash rose far out on the water where the shot struck.

The yard went silent.

Then, slowly, scattered cheers began—not from everyone, but from enough people to change the air. Men who’d laughed now looked unsettled. Others looked relieved. A few looked angry, as if success had stolen their right to complain.

Caldwell let out a breath he hadn’t allowed himself to take.

Mae watched the smoke drift away and felt something complicated.

They’d done it. They’d made the past speak loudly again.

But the sound didn’t feel like victory.

It felt like necessity wearing an old costume.

4) Liberty Ship 441 Leaves With a Relic and a Promise

Two nights later, Liberty Ship 441 slid out of the yard and into the harbor channel, escorted by tugboats and watched by workers who stood in rows like witnesses.

Mae, Ida, and Gloria stood on the pier, hands shoved into coat pockets against the cold.

The cannon was visible on the stern—an iron shape that looked almost theatrical against the ship’s new paint.

Ida muttered, “I still hate it.”

Mae didn’t disagree. “Me too.”

Gloria’s eyes stayed on the ship as it moved away. “But I’d hate it more if she left with nothing.”

Caldwell approached them, hat tucked under his arm. He looked less like a clipboard now and more like a man carrying weight.

“They’re sailing under orders,” he said. “Convoy joins tomorrow.”

Mae nodded. “We did our part.”

Caldwell hesitated. “You did more than your part.”

Ida’s mouth tightened. “Don’t make it sentimental, Lieutenant.”

Caldwell almost smiled. Almost. “Not sentimental,” he said. “Just… true.”

He cleared his throat and added, quieter, “If it works out there—if it buys them even seconds—people will argue about it for years. They’ll say it was genius. Or desperation. Or reckless.”

Mae watched the ship’s wake cut the water like a pale seam.

“Let them argue,” she said. “As long as the crew comes back to hear it.”

5) The Ocean Doesn’t Care What Year Your Weapon Was Made

Three days later, in a stretch of Atlantic gray that looked the same in every direction, Liberty Ship 441 ran with her convoy under low clouds.

On her stern, the old cannon sat strapped down and ready, its barrel covered against spray. Sailors joked about it during calmer moments, calling it “Grandfather” and “Old Thunder” and worse names when they were tired.

But they watched it too—because in war, people watched whatever they could hold onto.

Near dusk, the lookout called it first: a ripple, a shape, a suspicion on the water.

Then the convoy’s mood shifted. Escorts tightened their arcs. The sea seemed suddenly crowded with unseen possibilities.

On 441’s bridge, Captain Hollis gripped the rail, eyes narrowed. “Where?”

The lookout pointed. “Starboard. Far.”

A dark form broke the surface—low, long, wrong. Not a whale. Not debris.

A submarine, surfaced, bold enough to show itself for a shot.

On deck, men ran to stations. The old cannon crew—trained in rushed drills—yanked the cover free and swung the barrel with strained effort. It moved slower than a modern mount would have, but it moved.

Captain Hollis’s voice cut across the ship. “If it’s close enough, use it.”

The words felt unreal: use the antique.

The submarine turned slightly, as if lining up. A flash winked near its bow—something launched, something meant for the convoy.

An escort vessel surged toward it, throwing up spray.

But the submarine’s presence alone was pressure. It forced choices. It threatened chaos.

On 441’s stern, the cannon crew worked with frantic discipline. Powder. Load. Ram. Set.

The ocean rocked them as if trying to make them miss.

“Hold!” the gun captain shouted.

The submarine’s silhouette grew clearer for a heartbeat between swells.

“Fire!”

Old Thunder spoke.

The boom tore across the water, heavy and old, shaking the stern like a giant hand. Smoke burst outward and was ripped by the wind. The shot arced low—too low, some thought—then struck the water near the submarine with a violent splash.

Not a direct hit. But close enough to make the submarine flinch.

It dipped, then rose, then turned sharper than before, as if startled that the merchant ship had answered.

Another shot from the cannon—this time the splash was closer, and the submarine disappeared beneath the surface in a hurry that looked like fear.

The escort vessel surged over the spot, dropping charges that turned the sea into rolling thunder. The water churned. The convoy tightened. Men held their breath as if the ocean might listen.

Minutes stretched into an hour.

No more surfaced shapes appeared.

No easy celebration came.

Because everyone aboard knew what had happened wasn’t a clean win. It was a narrow avoidance. A moment bought.

And the strangest part—the part nobody wanted to say out loud—was that a century-old weapon had forced a modern predator to hesitate.

6) Back in the Yard, the Arguments Arrive Before the Ship Does

Word reached the shipyard by radio relay and rumor within a day.

Bay Three buzzed like a hive with a crack down its middle.

“They fired it?” a welder asked, wide-eyed.

“They made it dive,” someone else whispered.

Haskins sneered, but his sneer looked shaky now. “Luck.”

Mae stood at her station, listening without joining.

Gloria leaned beside her. “They’re going to make it a story.”

Mae nodded. “They always do.”

Ida wiped oil from her hands. “They’ll either call it heroic or humiliating. No in-between.”

A supervisor came running down the bay with a paper in his hand, face flushed. “Donnelly! Kline! Reyes!”

Mae braced. “What now?”

He waved the paper like it was a trophy. “Navy wants more. They’re asking if we can restore another. And another.”

Ida stared at him. “Restore more museum cannons.”

The supervisor grinned like he’d just been handed a promotion. “They say it worked.”

Gloria’s face tightened. “It worked once.”

Mae took the paper, scanning. The wording was careful, official, full of phrases that tried to sound confident:

interim armament solutions… effective deterrent… proceed with expansion…

Mae looked up. “This isn’t just about one ship.”

Ida’s voice was quiet. “This is about admitting the modern guns never arrived.”

Gloria added, “And making us responsible for the gap.”

The supervisor’s grin faded. “Isn’t that what you want? To help?”

Mae’s gaze hardened, not at him, but at the whole problem. “We already helped,” she said. “Now they’re going to make the shortage our identity.”

Ida nodded slowly. “They’ll praise us in public and blame us in private if something goes wrong.”

Gloria’s eyes flicked toward the harbor, toward the water that never stopped looking hungry. “And if this becomes policy, the arguments will get louder.”

Mae folded the paper. “Then we do what we always do,” she said.

The supervisor blinked. “Which is?”

Mae’s voice was steady. “We build what’s needed. We build it right. And we remember who pays the price if it isn’t.”

7) When Liberty Ship 441 Comes Home, Nobody Feels Clean

Two weeks later, Liberty Ship 441 returned—scarred, salt-streaked, alive.

Mae, Ida, and Gloria stood on the pier again as she eased into the harbor. The old cannon was still there. It looked darker now, as if the ocean had aged it another fifty years.

Crewmen waved. Not cheering—just acknowledging, the way people do when they’ve been far too close to the edge and don’t want to tempt it again.

Captain Hollis came down the gangway and walked straight toward the three women. He didn’t bother with speeches.

He simply nodded at the cannon behind him and said, “Your relic made the sea hesitate.”

Mae didn’t know what to say to that.

Ida spoke first, because Ida always did. “Did it save you?”

Hollis’s eyes flicked away, just once. “It didn’t solve the ocean,” he said. “But it bought time. And time is… everything.”

Gloria asked, quietly, “Did anyone not make it back?”

Hollis held her gaze. He didn’t lie. “We lost people in the convoy,” he said. “Not on my ship. But close enough that the sound carried.”

Mae felt the truth settle in her chest: even when you succeed, the war collects somewhere else.

Hollis looked at the shipyard behind them—women and men watching, waiting for a story.

“They’re going to call you symbols,” he said.

Mae’s mouth tightened. “We didn’t ask to be.”

Hollis nodded. “Nobody does.”

He tipped his hat—simple, respectful—and walked away.

Mae stared at the cannon again, at the iron barrel that had traveled from a quiet pedestal to the worst ocean on earth and back.

Ida exhaled. “So what now?”

Mae unfolded the Navy paper again, the request for more restorations.

“Now,” she said, “we turn the argument into steel.”

Gloria frowned. “What does that mean?”

Mae looked at her, eyes tired but fierce. “It means we don’t let them pretend this is normal. We don’t let them write the shortage into tradition. We use the relic because we have to, and we keep demanding the modern guns until they arrive.”

Ida nodded. “And if they never arrive?”

Mae glanced at the harbor, at the ships lining up like moving shadows.

“Then we keep building,” she said. “And we keep remembering what the ocean doesn’t care about.”

Gloria’s voice softened. “What’s that?”

Mae looked at the cannon, then at the people, then at the water.

“Pride,” she said. “And excuses.”

The gulls screamed overhead again, and the harbor wind carried the smell of salt and paint and something else—something like a warning that never really left.

The war had dragged a 19th-century weapon into a 20th-century nightmare, and a group of shipyard women had made it speak.

Not because they believed in old iron.

Because the modern world had failed to deliver on time—and someone still had to sail.