They Opened a Frozen Boxcar of Chained German Women POWs—Then One American Sergeant Said Five Quiet Words That Stopped Time and Made Everyone Break Down

The boxcar looked like every other boxcar in the rail yard—until you got close enough to see the ice.

It clung to the wood in thick, uneven patches, like the train itself had been dragged through a river and left to harden in place. A thin crust rimmed the metal latch. The stenciled numbers were half-buried under frost, and someone had painted over an old marking so hastily that the brush strokes still showed.

Sergeant Jack Mallory didn’t like boxcars.

He didn’t like rail yards either. Too many blind corners. Too many shadows that could hide a surprise. Too much history piled in one place, all of it heavy and sharp.

The wind shoved through the broken windows of a nearby station house, making the glass fragments sing. Snow drifted between the tracks in long, pale ribbons. Somewhere down the line, an engine ticked as it cooled, each click a patient reminder that machines kept going even when men didn’t.

Mallory pulled his scarf higher and gave a quick hand signal. His squad moved with him—boots crunching, breath turning to fog, rifles held in a way that said ready without saying afraid.

They weren’t supposed to be here long. Command wanted the area checked, cleared, and left behind.

But Mallory had learned something about “quick checks” in winter: the cold always made things slower, and it always made the smallest mistakes louder.

A private named Larkin jogged up beside him. He was young enough to still look surprised by the world.

“Sergeant,” Larkin said, nodding toward the row of cars, “we found more.”

Mallory didn’t answer with words. He only lifted two fingers—show me—and followed.

They passed a flatbed with crates strapped down under tarps, then a cattle car with its door hanging open like a broken jaw. Past that, there were two freight cars that smelled faintly of oil and old grain.

Then they reached the boxcar.

It sat slightly apart, as if the rest of the train had tried to give it space. A thin chain looped around the door handle, knotted with a rough padlock.

Mallory stared at the chain for a long moment, the way a man stares at a thing that shouldn’t be necessary.

“Why lock a boxcar from the outside?” Larkin asked.

Mallory didn’t like the answer his mind offered.

He lifted his hand again, a signal for quiet. The men fanned out—one to cover the track, one to watch the station house, one to keep eyes on the tree line beyond the yard.

Mallory stepped closer and put his gloved palm against the wood.

Cold bit through the leather. The whole car felt like it had been storing winter inside.

He leaned his ear toward the seam of the door and listened.

At first he heard nothing but the wind.

Then—faintly—something else.

A sound that wasn’t the wind and wasn’t the train settling.

A weak, uneven scrape.

Like fingernails against wood, or a shoe dragging in a narrow space.

Mallory’s jaw tightened.

He took a breath, then rapped his knuckles on the door.

“Hello?” he called.

Nothing.

He rapped again, harder.

“Anyone in there?”

This time, the sound came again—closer, urgent. A muffled thud, then another, as if something inside had tried to stand and failed.

Mallory turned his head slightly. “Crowbar.”

Corporal Diaz handed it over. Diaz was built like a fence post and had the steady eyes of someone who could carry fear without dropping it.

Mallory slid the crowbar under the chain, tested the tension, and glanced at the lock.

“Cut it,” he said.

Diaz raised his bolt cutters. The metal jaws clamped down, and the lock snapped with a sharp, final pop that echoed between the empty buildings.

The sound seemed to freeze the air.

Mallory grabbed the handle and yanked.

The door didn’t move.

Ice held it like glue.

“Again,” he said, and Diaz helped him, both men pulling until their boots dug trenches in the snow.

The door shuddered—just a fraction—then stuck again.

Mallory felt impatience flare, hot against the cold. Not at the door. At whoever had left it like this.

“Back,” he told the men.

He swung the crowbar and struck the latch area—not wildly, but with controlled force. The wood vibrated under the blow. Frost cracked. The latch groaned like it hated to admit weakness.

He struck again.

On the third hit, the door lurched and slid open a foot.

A gust rolled out.

It didn’t smell like livestock or fuel or grain.

It smelled like breath trapped too long in a small space.

Mallory’s throat tightened.

He forced the door wider.

Light spilled into the darkness, and for one awful second, he thought the boxcar was empty because everything inside was so still.

Then he saw the eyes.

They caught the light one by one, reflecting it the way frightened animals do—wide, glassy, unblinking.

Figures sat huddled along the floor. Coats pulled tight. Scarves covering faces. Boots tucked under bodies. Some were slumped against the wall. Some lay down as if sitting had become too expensive.

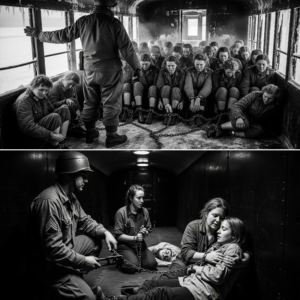

And along the center beam, a length of chain ran low, linking wrists together in small groups—metal on metal, heavy and unnecessary.

Women.

Young and middle-aged, their hair stuffed under caps or fallen loose in stiff strands. Their faces were pale from cold and exhaustion, cheeks hollow, lips cracked.

One of them tried to speak, but her voice didn’t arrive. Only a rasp of air came out.

Larkin made a sound behind Mallory—half gasp, half curse.

Diaz went utterly still.

Mallory stepped into the threshold and raised both hands, palms open, because instinct told him the wrong movement could break something fragile in the room.

He looked for threats first—because that was his job.

There were none.

No weapons. No traps. Just bodies and chains and winter.

His eyes found one woman near the door. She was leaning forward like she had tried to crawl toward the crack of light. Her hands were bound to another’s by a short chain. Her fingers were swollen, purple at the tips. Her eyelashes were crusted with frost.

She stared at Mallory with the blunt intensity of someone who had been living on one thought: Please don’t let this be the end.

Mallory swallowed, and the cold in his throat felt like glass.

He didn’t know her name. He didn’t know what uniform she had worn or what job she had done. He didn’t know what she believed.

None of that mattered in that moment.

He only knew what she was: human, freezing, and trapped.

Mallory leaned forward slightly, voice low—gentler than he intended, because something in the boxcar demanded it.

He said five words that were plain enough to fit inside any language:

“You’re safe now. You’re safe.”

The woman’s mouth trembled. Her eyes, so wide and fixed, suddenly flooded as if the words had knocked loose something she’d been holding together with raw will.

Then she collapsed—not falling so much as unfolding—head dropping to her chest, shoulders shaking in silent sobs.

It was like a signal.

Another woman made a broken sound and began to cry. Another tried to speak and couldn’t, her voice snagging on the way out. Someone in the back let out a long, shaking exhale that sounded almost like relief, almost like surrender.

The boxcar filled with soft, desperate noises—small human sounds that didn’t belong in a war.

Larkin stepped closer, eyes wide. “Sergeant… what do we—”

Mallory snapped out of the moment like a man surfacing from deep water.

He turned sharply. “Blankets. Now. Any you’ve got.”

Diaz was already moving. “We got some in the truck.”

“Run,” Mallory said. “And tell the medic. Tell him now.”

Larkin hesitated—still staring at the chains like they were a personal insult.

Mallory caught his gaze. “Move, Private.”

Larkin moved.

Mallory climbed into the boxcar. The air inside was so cold it felt dense, like breathing through cloth. He knelt near the woman by the door and held his hands up again.

“Easy,” he said. “No sudden moves. We’ll get you out. We’ll get you warm.”

The woman’s eyes searched his face as if she expected the words to reverse themselves. She tried to answer, but what came out was a whisper in a language Mallory didn’t understand.

He caught only one word—bitte—and he didn’t need a translator for the meaning.

Please.

Mallory nodded once, slow. “Yeah,” he said quietly. “Yeah. We got you.”

He looked at the chains.

A smaller padlock held the center line. It wasn’t a military lock—just a cheap industrial one, the kind you’d use on a storage shed.

Mallory’s anger sharpened into something clean.

Diaz returned with blankets and a medic, Specialist Carter, who had the tired, focused eyes of someone who’d seen too many forms of suffering and refused to be surprised by any of it.

Carter stopped at the door, took one look inside, and his mouth tightened.

“Holy—” Carter began.

Mallory cut him off without looking back. “No commentary,” he said. “Just work.”

Carter nodded once, professionalism snapping into place.

They moved fast, but careful—blankets first, draped over shoulders, tucked around knees. Some women flinched at the approach of hands; others leaned into the warmth like plants toward sunlight.

One woman, older, tried to stand and nearly fell. Mallory caught her elbow, supporting her like she weighed nothing and everything.

Carter checked pulses, pressed fingers to wrists, spoke in calm tones that didn’t demand understanding. He glanced at Mallory.

“Sergeant, they’ve been in here a while,” Carter murmured. “We need heat, but not too fast.”

Mallory nodded. “We’ll do it right.”

Diaz raised his bolt cutters again and looked at Mallory, silent question.

Mallory pointed at the central padlock. “Cut it.”

The snap sounded louder inside the boxcar.

The chain loosened, slack falling to the floor with a metallic sigh that felt like the car itself was relieved.

Some of the women stared at the fallen chain as if they didn’t believe it had really happened. One reached down with shaking fingers and touched the links. Her face crumpled.

Carter spoke again, softer. “We need to move them. One at a time. Keep them covered.”

Mallory turned to Larkin, who had returned with more supplies and looked like he’d aged five years in five minutes.

“You’re on carrying duty,” Mallory said. “Gentle. Like you’re holding your little sister after she fell off a bike. You understand?”

Larkin swallowed hard. “Yes, Sergeant.”

Mallory moved deeper into the boxcar, scanning faces, making quick decisions about who could walk and who couldn’t. He spotted another woman sitting stiffly against the wall, jaw clenched as if she refused to give the cold the satisfaction of seeing her tremble.

Her eyes were sharp, bright with a dangerous kind of pride.

When Mallory knelt near her, she didn’t look away.

She spoke in careful, broken English. “You… American?”

Mallory nodded. “Yeah.”

She stared at him for a moment, then asked, voice rough. “Why… help?”

Mallory paused.

It was a fair question in a war full of unfairness.

He answered honestly, because anything else felt like a lie that would poison the air.

“Because you’re freezing,” he said. “And because this isn’t how people should be left.”

Her lips pressed together. The pride in her eyes fought with something softer and older—something that had nothing to do with flags.

She looked down at the chain on the floor and whispered, almost to herself, “Not… how people.”

Mallory didn’t argue. He just held out the blanket.

After a long second, she took it.

Outside the boxcar, the squad had set up a makeshift warming area in the station house—broken windows patched with canvas, a stove coaxed to life, water heated slowly. Someone found spare mittens. Someone else dug out a tin of sugar and dropped it into tea like it was an offering.

As each woman was carried or guided out, the snow seemed to brighten around them, the morning light making their exhausted faces look strangely young.

Some soldiers stared too long. Not with cruelty—more with confusion. War had taught them to see enemies as shapes at a distance. Up close, wrapped in blankets, shivering and silent, the shapes became people again, and that was harder.

A staff lieutenant arrived, breathless, looking from Mallory to the women and back.

“Sergeant,” he said, voice tight, “what is this?”

Mallory kept his voice steady. “Prisoners,” he said. “Left in a locked car. They need medical attention. Then they go to proper holding.”

The lieutenant’s eyes flicked toward the chain, now coiled like a dead snake near the track.

“Who did that?” the lieutenant asked.

Mallory shook his head. “Don’t know,” he said. “But it ends here.”

The lieutenant hesitated, then nodded. “Good.”

Inside the station house, Carter worked with brisk calm. He checked hands and feet, watched for dizziness, insisted on slow sips of warm liquid. He spoke to Mallory under his breath.

“Some of them are in bad shape,” Carter said. “Not beyond help—just… pushed too far.”

Mallory watched one woman stare at her cup as if she didn’t remember how cups worked.

“We keep them alive,” Mallory said.

Carter studied him for a moment. “That’s the plan,” he agreed.

An interpreter finally arrived—Private Nakamura, a Japanese-American soldier with a sharp mind and a voice that carried calm even when the world didn’t deserve it.

Nakamura approached the group gently, speaking German in a careful tone. The women reacted like flowers turning toward sunlight. Questions poured out—fast, strained, overlapping.

Nakamura listened, then turned to Mallory.

“They thought they were being moved to a camp,” Nakamura said quietly. “Train stopped during the retreat. Nobody came back. They said they knocked for… days.”

Mallory’s stomach turned. “Days.”

Nakamura nodded. “They stopped knocking when their hands… couldn’t.”

Mallory looked away for a moment, jaw clenched so hard it hurt.

Across the room, the proud woman from the boxcar sat with a blanket wrapped around her shoulders like a shield. Her eyes tracked Mallory. When Nakamura spoke to her, she answered in short bursts, then finally looked at Mallory again.

Nakamura translated.

“She says… she didn’t expect kindness,” Nakamura said. “She says she expected—”

He stopped himself, choosing a safer word.

“She expected… bitterness.”

Mallory exhaled slowly. “Tell her,” he said, “bitterness doesn’t keep people warm.”

Nakamura translated.

The woman blinked, surprised by the simplicity, then gave the faintest nod.

Later, when the worst of the shaking had eased and the women could sit without swaying, Mallory stepped outside for air.

The cold hit him again, but now it felt different—less like an enemy, more like a fact.

He looked back at the boxcar. The open door gaped like a mouth that had finally stopped holding its secret.

Diaz came up beside him, hands in his pockets.

“You said the right thing in there,” Diaz murmured.

Mallory didn’t answer at first. His breath drifted up and vanished.

“What I said wasn’t clever,” Mallory finally replied.

Diaz shrugged. “Didn’t need to be.”

Mallory stared at the tracks. “I keep thinking,” he said quietly, “how close they were to nobody opening it.”

Diaz nodded once, slow. “Yeah.”

Mallory swallowed. “All it took was a chain and cold.”

“Don’t forget the lock,” Diaz said, voice low.

Mallory’s eyes narrowed. “Yeah,” he said. “The lock too.”

A truck arrived to transport the women to a proper facility. Carter insisted on extra blankets, insisted on slow movement, insisted on staying nearby. Mallory watched as the women climbed aboard—some helped, some carried, all of them wrapped in warmth that looked almost unreal on their shoulders.

The proud woman paused at the truck step and looked back at Mallory.

She said something quietly to Nakamura.

Nakamura turned.

“She wants to know your name,” he said.

Mallory hesitated, then answered. “Mallory. Jack Mallory.”

Nakamura translated.

The woman repeated it softly, as if testing the sound. Then she spoke again, and Nakamura’s eyebrows lifted.

“What?” Mallory asked.

Nakamura’s voice softened.

“She says… she will remember the first words,” he said. “She says those words… unlocked more than the chain.”

Mallory’s throat tightened unexpectedly. He stared at the truck’s wooden side rail, suddenly unable to find a clean reply.

So he did what he’d done inside the boxcar.

He kept it simple.

“Tell her,” Mallory said, “the war ends someday. People have to live after.”

Nakamura translated.

The woman held Mallory’s gaze for a moment longer, then nodded once and climbed into the truck.

As the vehicle rolled away, tires crunching over snow, Mallory stood still and listened until the engine sound faded into the wind.

Behind him, the rail yard remained cold and silent, full of forgotten cars and abandoned plans.

But one boxcar sat open now, empty of its secret.

Mallory walked back toward it, glanced inside, and saw only the scraped floor, the faint marks where bodies had been pressed into wood, the coiled chain left behind like a rejected idea.

He reached down, picked up the lock, and turned it over in his gloved hand.

So small, he thought.

So sure of itself.

He tossed it into his pocket—not as a souvenir, not as a prize, but as proof that the ugliest things in war weren’t always loud.

Sometimes, they were quiet.

Sometimes, they were the shape of a cheap padlock in a freezing morning.

And sometimes, the only weapon that mattered in that moment was not a rifle or a rank—

but five plain words spoken at the right time, into the darkest place, like a match struck in the cold:

You’re safe now. You’re safe.