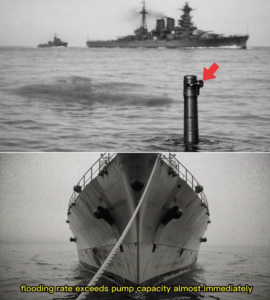

They Laughed Off the “Underwater Threat” — Then HMS Barham Lit Up the Night in 1941, and a Single Chilling Signal Proved Command Had Been Wrong All Along

The sea has a way of making confident voices sound smaller.

On land, a man can point at a map and feel powerful—he can tap a coastline, draw an arrow, and pretend the world will obey the pencil. At sea, the pencil doesn’t matter. The horizon doesn’t care who outranks whom. And the water—dark, heavy, endless—keeps its own counsel.

I learned that aboard HMS Barham in the autumn of 1941, when the Mediterranean air still carried summer heat in the daylight but cooled sharply after dusk, and when every night watch felt like you were listening for a secret you didn’t have the right to hear.

People think a battleship is loud all the time: engines, chains, boots, shouted orders. The truth is that the loudest parts are often the pauses—the moments when men stop talking because they don’t want to give fear a name.

We were a floating city of steel. We had routines as dependable as tide tables: morning scrubs, signal drills, maintenance checks, tea that tasted faintly of metal, and that constant low vibration that you only noticed when it briefly stopped. We had jokes, too—thin jokes, repeated too often, because repetition can feel like armor.

And we had the one conversation nobody wanted to linger on: the thing beneath the water.

It was the kind of threat you couldn’t look at. No silhouette in the sky, no distant smoke trail. Just the idea of something patient and unseen, following you like a thought you can’t shake.

We called it “the underwater threat” because some words felt too sharp to carry around all day.

The officers discussed it with careful calm. The younger hands spoke about it in half-sentences, pretending they didn’t care. The veterans didn’t speak about it at all, which told you everything.

Still, there were warnings—more than a few.

They came in the form of signals picked up by the wireless room, fragments of reports passed down through channels, and the uneasy way escorts sometimes changed position without explanation. Once, in Alexandria, I saw a lieutenant with a weathered face quietly replace the same chart on the table three times, as if a different angle might make the sea safer.

And then there were the rumors that ran faster than any official bulletin.

A merchant ship that didn’t arrive when it should have.

A destroyer that returned with scorch marks and silence.

A convoy that suddenly turned back for no reason anyone would explain.

When you live with uncertainty long enough, you start to treat it like background noise. That’s how the mind protects itself. But the sea doesn’t protect anyone. The sea simply waits.

My name doesn’t matter. I was a junior signalman then—one of the men who carried messages, recorded them, repeated them, made sure the right lamps flashed at the right times, and kept the fleet’s language from becoming a jumble.

I liked my work because it gave me something solid in a world made of moving parts. A signal was either correct or it wasn’t. A lamp either flashed or it didn’t. When you’re young in wartime, you cling to anything that feels certain.

But certainty is a trick. It holds until it doesn’t.

A few days before the end, we received a warning that didn’t feel like the others.

It came late in the afternoon, when the sun sat low and orange over the water and the ship’s shadows looked longer than they should. The message came through the proper channels, coded and neat, and then—quietly—there was a second message, unofficial, passed from one watch officer to another with the careful tone of someone repeating something they didn’t want to believe.

There had been sightings.

Not sightings like aircraft. Not smoke on the horizon. Sightings like absence—a periscope ripple, a glint that was gone before you could point at it, a suspicious calm patch on the surface where the wind should have been.

In the mess, a petty officer leaned close and said, “They’re out there.”

“Who’s out there?” someone asked, though everyone knew what “they” meant.

“The watchers,” he said. “The ones you don’t see.”

A man at the end of the table snorted. “We’ve got destroyers, we’ve got escorts. We’ve got brains at command. They know.”

The petty officer’s eyes stayed flat. “Brains don’t float,” he said, and went back to his tea.

Later that evening, I was sent with a packet to a small briefing room where officers were gathered around a chart. The air smelled of ink and sweat and the sharp tang of tobacco. A single lamp swung slightly with the ship’s motion, casting moving shadows across the map.

An intelligence officer—thin, serious, with the kind of voice that tried to be steady—was speaking about patterns. About enemy tactics. About the likelihood of an unseen approach.

He pointed to a stretch of sea and said, “This corridor has been active.”

A senior officer—one of the confident ones—leaned back and folded his arms. “Active,” he repeated, as if tasting the word. “We’ve sailed this corridor before.”

“Yes, sir,” the intelligence officer said. “But conditions have shifted. The reports—”

“The reports are always shifting,” the senior officer replied. “If we jump at every shadow, we’ll never move at all.”

There were a few murmurs of agreement. Not everyone, but enough.

The intelligence officer tried again, carefully. “The pattern suggests a patient tracker. A hunter. If we—”

“Enough,” the senior officer said, and tapped the table once, as though closing a book. “We maintain course. Escorts remain alert.”

The word “alert” floated in the air like a charm. As if saying it would make it true.

I stood there with my packet pressed against my chest and thought: So that’s it. That’s the answer. Maintain course.

It felt too easy. But I was young, and young men often assume that people higher up must know something you don’t.

That night, I went out onto the deck just before my watch. The sky was clear, stars hard and sharp. The ship cut through the water with its usual confidence, leaving a bright trail of foam that looked, from above, like a signature.

I remember thinking how visible we were. Not in the air—there were no lights, no carelessness. But visible in the way a huge thing is visible even in darkness, because it changes the world around it.

I looked down at the water and saw nothing but moving black.

That, in hindsight, was the problem.

The day of November 25, 1941, began like a day that didn’t intend to be remembered.

We were part of a formation at sea, moving with purpose. The Mediterranean sun was deceptive—warm on your skin, bright in your eyes—while the air carried that dry bite that made you thirsty even when you weren’t working. We had been at it long enough that time blurred into watches and meals, into the endless cycle of duty.

By afternoon, the mood shifted.

It was subtle. It always is.

An escort changed position slightly, its wake crossing ours at an angle that made the men on deck glance up. A lookout lifted binoculars and held them too long on a blank patch of sea. The officers’ voices tightened by a fraction.

And then, just before dusk, there was an odd quiet—like the world inhaled.

I was at my station, checking lamps and instruments, when I felt it first: not a sound, not exactly, but a pressure change in the air, a strange sense of the ship pausing in its stride.

A heartbeat later, the deck shuddered under my boots.

It was a deep удар—an impact you felt in your bones more than you heard. The kind of jolt that makes your stomach drop because your body knows, before your mind can label it, that something has gone wrong.

Men froze. Tools clattered. A voice shouted something I couldn’t catch.

Then came a second удар, close on the first—another blunt punch from below the waterline.

The ship, which had always felt invincible in its mass, suddenly felt… vulnerable. Like a giant that had been tapped in the knee.

I heard the call over internal communications—strained, clipped—words tumbling fast. Damage reports. Compartments. The language of urgent problem-solving.

Training kicked in. It always does.

I ran messages. I repeated signals. I watched officers lean into decisions the way sailors lean into a gale—shoulders forward, eyes narrowed, moving because stopping would mean thinking too hard.

For a moment, it felt like we might contain it. That was the most dangerous illusion of all.

The Barham began to list—not sharply at first, just a slow tilt that made loose objects slide, made men widen their stance. The horizon line shifted in a way that made you realize how much your mind depends on “level” to feel safe.

“Steady!” someone barked. “Hold on!”

I remember grabbing a railing and feeling the metal cold under my palm.

A few seconds stretched into something longer. The ship groaned—deep, low, like an old door being forced. Somewhere below, a muffled roar echoed through the hull. Not one sound, but a series, like distant thunder trapped in a box.

Then, in the middle of that chaos, there was a strange moment of clarity.

A signal lamp winked from an escort—fast, urgent flashes.

I didn’t have time to translate it fully, but I caught enough: Warning. Danger. Move.

As if we had any choice.

The list grew steeper. Men began to move differently—not in ordered lines now, but in quick bursts, grabbing at ladders, hauling themselves up angles that used to be vertical.

You could see it on faces: the shift from “we can fix this” to “we need to survive this.”

Still, command tried to command.

Over the ship’s voice system, an officer’s voice came through—steady with effort. “All hands—remain calm—follow instructions—”

The words sounded brave. They sounded correct.

They also sounded thin against the weight of what was happening.

And then came the moment that erased every other sound.

A third удар—different from the first two. Not just a punch, but a tearing jolt, as though the sea had grabbed the ship and twisted.

For a fraction of a second, there was silence.

And then the world turned white.

Not “bright.” Not “lit.” White. The kind of light that makes your eyes water and your mind go blank. A towering flare rose from the ship’s center, and the air slapped my face with heat so sudden it felt like opening an oven door inches from your skin.

The blast wasn’t just loud. It was total—it swallowed the sky, the sea, the voices, the structure of the world.

I remember seeing men thrown off balance like toys. I remember the deck tipping harder, the rail rising, the horizon rolling.

And I remember something else, something I didn’t understand until much later:

In that instant, orders stopped mattering.

Not because anyone became disloyal. Not because discipline broke. But because the universe had changed the rules. A voice over a speaker can’t argue with gravity. A commander’s intent can’t negotiate with fire and water.

After the blast, the ship was no longer a ship in the way we understood it.

It was a structure in collapse.

The list became a tilt became a slide. Men scrambled, slipping on metal that had become an angled wall. Some tried to help others. Some grabbed ropes. Some simply stared, as if their minds refused to accept what their bodies already knew.

I found myself moving without thinking, climbing toward what had become “up,” my hands burning where they touched hot steel. The air was thick with smoke and salt and that sharp, acrid scent you never forget once you’ve tasted it.

Someone grabbed my arm—hard. A face I recognized, smeared with soot, eyes wide. He shouted something, but the sound was torn apart by wind and noise.

We reached an edge that used to be a side. Below—now “below” was a concept that didn’t behave properly—the sea churned, reflecting fire like shattered glass.

For a moment, the Barham hung there at an impossible angle, as if the ship itself was hesitating.

And then it began to roll.

The sky swung. The sea rose. The ship’s bulk turned over with a slow, dreadful certainty.

Men jumped. Some slipped. Some vanished behind structure. I felt hands push me forward—maybe my own, maybe someone else’s.

The water hit like a wall—cold enough to steal your breath, heavy enough to make you forget you had lungs.

When I surfaced, I tasted oil and salt. The air was filled with shouts, coughing, splashing. The sky above was darkening into night, and the sea around us was lit by fire that didn’t belong on water.

I turned and saw the Barham—or what was left of her—still rolling, her great shape outlined by flames and smoke.

And then, as quickly as she had been massive and present, she wasn’t.

The sea swallowed her with a brutal efficiency. The noise diminished to crackling and distant cries. A slick spread across the surface, shining under the firelight.

There are images from that night that I can’t place in order. Time broke into fragments.

A life ring that drifted past me, empty.

A man clinging to wreckage, lips moving silently.

The thump of an escort’s propellers somewhere close, then farther, then close again.

Voices calling names that the wind carried away.

At some point, a smaller ship drew near—an escort, low and fast. Men threw lines. Hands grabbed at us. I remember being hauled aboard like a sack of wet clothes, coughing until my chest felt split.

Someone wrapped a blanket around my shoulders. Someone pressed a mug into my hands. The mug shook so hard that tea spilled down my fingers, and I didn’t even feel it.

I looked back at the sea where the Barham had been.

There was nothing to look at.

Just dark water and a drifting sheen and smoke that curled upward into the night.

That emptiness was worse than any sound.

In the hours after, the world became paperwork again.

That sounds cruel, but it’s true. The navy, like any vast machine, has to keep turning. Men have to be counted. Signals have to be sent. Decisions have to be made, not because anyone wants to, but because stopping would mean admitting that chaos has won.

They took our names. They checked us for injuries. They placed us in groups like items that needed sorting.

And then, something strange happened.

We were told—quietly—to say nothing.

Not “nothing” in the sense of secrecy forever. Nothing in the sense of for now. There were reasons given in careful language: morale, security, the danger of information traveling too fast.

At first, it felt unreal—how could you keep quiet about a ship that had just lit up the sea? But then I understood: silence was another kind of defense.

The sea could take a battleship. Command could, at least, try to keep the news from feeding panic.

So the loss became a locked door, and we—shivering, exhausted, not quite believing we were still breathing—were the people who had seen what was behind it.

That’s where the mystery began.

Not in the way people think of mystery—no detectives, no riddles with tidy answers. The mystery was simply this: how something so enormous could vanish so quickly, and how the world could continue the next day as though it hadn’t.

When you’re inside such a moment, you keep replaying the minutes before it happened, looking for the seam where reality came undone.

I thought of that briefing room. The intelligence officer pointing at the chart. The senior officer brushing off the warning with that calm certainty.

“If we jump at every shadow,” he’d said, “we’ll never move at all.”

He hadn’t been foolish. Not exactly. He had been operating under a rule that works most of the time: if you hesitate too much, you lose initiative. If you see danger everywhere, you become paralyzed.

It’s a sensible rule—until the one danger you didn’t name reaches up and touches you.

Out at sea, you don’t get graded on how sensible your rule was. You get graded on whether you survive.

Days later, after the shock had settled into a dull ache, I found myself in a quiet corner of a dockyard office, waiting for instructions. A senior signals officer sat across from me, sorting papers. He had the look of a man who had stopped being surprised years ago.

I couldn’t keep the question in my mouth any longer.

“Sir,” I said, “did command really think it couldn’t happen?”

He paused, then looked up slowly.

“No,” he said. “Command knew it could happen.”

He tapped a pencil against the desk. “That’s the part you’ll learn to hate. They knew. They always know it can happen. The problem is deciding when ‘can’ becomes ‘will.’”

I swallowed. “So why—”

He raised a hand gently, not to silence me, but to shape the thought.

“Because you can’t run a fleet on fear,” he said. “You also can’t run it on hope. You run it on judgment.”

His eyes held mine, tired but steady.

“And judgment is imperfect,” he said. “Even when it belongs to good men.”

I stared down at my hands. They were still rough from salt and rope.

“Then what do we do?” I asked quietly.

The officer’s mouth tightened—not unkindly. “We remember,” he said. “We correct. We adapt. And we carry the ones who didn’t come back in the way we do our jobs.”

He slid a paper across the desk toward me—new orders, new postings, new routines.

The machine kept turning.

But in my mind, the night of November 25 never fully ended.

Years later, people would talk about the Barham in clipped phrases, as though shortening the sentence made it easier to hold. They would describe the suddenness. The brightness. The way the ship seemed to vanish between one breath and the next.

Some would call it bad luck.

Some would call it the cost of war.

But for those of us who were there—those of us who heard the first deep удар under our feet and felt the ship tilt—it was something else.

It was the moment when certainty broke.

The moment when a “dismissed risk” became a reality so loud it rewrote the air.

And the strangest part—the part that still makes my stomach tighten when I think about it—is not the blast itself.

It’s the minutes before.

The calm voice in a briefing room.

The confident tap on a chart table.

The assumption that the sea would behave because it had behaved yesterday.

Because that’s where the danger lives—not only in the unseen threat beneath the surface, but in the human habit of believing that because we survived once, we’ll survive again.

The sea doesn’t reward habit.

It rewards respect.

On some nights, when the air is still and the horizon is clean and the world seems stable, I can still hear the faint crackle of a lamp signal in my head—warning, danger, move—flashing too fast to be fully translated before everything changed.

And I think about how, in war, you can follow every instruction you’re given and still be caught by what wasn’t written down.

That’s the truth HMS Barham left behind in 1941—floating on dark water long after the flames went out:

A fleet can plan. A commander can judge. A ship can be mighty.

But the sea only needs one quiet moment to remind you who was in charge all along.