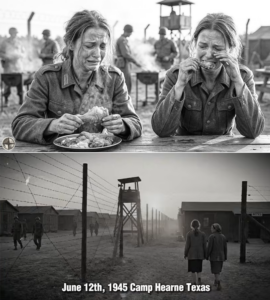

“They Called It the ‘Golden Bird’—But No One Expected This: German Women POWs Broke Down in Sob-Shocking Tears After One Bite of America’s Mysterious Fried Chicken.”

The first rumor arrived on a Thursday, slipping through the barracks the way warm air sneaks under a door in winter.

It started as a whisper near the washbasins—two women leaning close, voices low, hands moving as if shaping a secret. Then it rolled to the bunks, to the laundry line, to the small circle that always formed around the stove when the wind made the tin roof sing.

“Tomorrow,” someone said, eyes bright with a kind of fear. “They’re bringing it tomorrow.”

“What is ‘it’?” Lotte asked, though she already knew the answer would be something impossible. Something the mind invents when it needs comfort.

They called it many things before it ever appeared: the golden bird, the crispy miracle, the American feast. It was all the same dream, wrapped in different words.

Fried chicken.

Even the phrase sounded strange on the tongue—two plain words that were somehow too rich for the camp. Lotte had been in the women’s compound for months, long enough to stop counting days and start counting seasons by the feel of dust on her skin. She knew the routines: morning roll call, work detail, a lunch that was more a pause than a meal, an afternoon that dragged like a heavy blanket, and then night—always night—when thoughts grew louder.

Food was the loudest thought of all.

Not because they were starving in the dramatic way stories liked to tell. They were fed. They were kept alive. But their stomachs remembered a different life—one where food meant more than fuel, more than measured portions and thin soups. Their mouths remembered holidays, birthdays, the smell of butter. Their hearts remembered tables.

So when the rumor of fried chicken came, it felt like a crack in the sky.

“Who told you?” Lotte asked.

A woman named Grete, older than most of them, shrugged. Grete’s face had a permanent tightness at the corners of her mouth, as if she was always bracing for bad news. “A guard said it. Not the stern one. The soft-spoken one. He heard it from the kitchen.”

“The kitchen,” Lotte repeated, as if the word itself could conjure scent and heat. The camp kitchen was a distant building where the air sometimes carried hints of things they never saw—coffee on cold mornings, onions when the cooks had them, a sweetness once that made everyone turn their heads like dogs catching a trail.

“Why would they bring something like that here?” asked Anke, who slept on the bunk above Lotte and spoke with a cautious intelligence, as though she didn’t trust joy.

Grete’s eyes narrowed. “Because America likes to show what it can do.”

“That’s not an answer,” Anke said, but her voice softened. “I mean—why now?”

No one had a satisfying reason. Maybe it was a holiday. Maybe a local church group. Maybe a commander had a birthday. Maybe it was nothing at all and the rumor would evaporate by morning.

But the thought of crispy, salty meat—real meat, not gray and boiled until it surrendered—spread through the compound with a power that made logic feel irrelevant.

That night, Lotte lay awake listening to the steady breathing of dozens of women and the distant click of boots on gravel. In her mind, she tried to imagine the chicken. She had eaten chicken before the war, of course—roasted, stewed, stretched with potatoes when times were hard. But “fried chicken” sounded like something from a poster: impossible abundance, golden crust, oil that could be spared.

Her stomach tightened with longing.

Then, in a way that surprised her, she felt anger too. Anger at her own hunger, at being so easily swayed by a rumor. Anger at the idea that a piece of food could make her forget everything else—where she was, why she was here, what had been taken and what had been lost.

She closed her eyes and told herself she would not hope.

But hope is stubborn. It grows in the smallest cracks.

Friday arrived with a bright, cold sun that made the barbed wire glitter as if it had been strung with glass beads.

At roll call, the women stood in their rows, breath turning to fog. Some kept their eyes forward. Others stole glances toward the gate, searching for any sign of delivery trucks or unfamiliar movement. Lotte tried not to look. She failed.

The gate remained ordinary. The guards remained ordinary. The world remained, on the surface, exactly as it had been the day before.

Work detail pulled them away—laundry, mending, sorting supplies, tasks that filled hands but not hearts. The rumor rode with them anyway, perched on every tongue.

“Do you think it’s true?”

“My cousin once saw Americans eat like that—whole pieces of meat in their hands.”

“If it comes, I don’t want to see anyone rush. We must keep our dignity.”

“Dignity doesn’t fill your stomach,” someone muttered, and laughter rippled—thin, guilty laughter, the kind that tries to pretend it isn’t desperate.

Lotte ended up assigned to the sewing room, where fabric scraps and the smell of old uniforms made time feel stitched together. Anke was there too, her fingers moving quickly as she repaired seams with a precision that suggested she had once planned a life where such skill mattered for something other than survival.

Around midday, the door swung open and the soft-spoken guard stepped inside.

His name was Miller. That was all they knew. He was young enough to look like a boy if you ignored the uniform, and he had a habit of clearing his throat before speaking, as if he was always apologizing for interrupting.

“Ladies,” he said in English first, then repeated in careful German that sounded practiced. “There will be… an extra meal today.”

The room went very quiet.

Anke’s needle froze mid-stitch. Lotte felt her pulse behind her ears.

Miller glanced at the floor and then back up, his cheeks slightly red. “A community group… brought something. It’s… a taste of home for us. But it’s enough to share.”

Grete, who was also in the sewing room, leaned forward. “Is it true?” she asked, voice sharper than a pin. “Is it fried chicken?”

Miller’s mouth twitched, as if he was trying not to smile. “Yes. Fried chicken.”

For a moment, the words didn’t land. They hovered in the air, absurd and bright.

Then someone exhaled a shaky breath. Another woman pressed her hand to her mouth. Lotte looked at Anke and saw something she had never seen there before: naked, unguarded yearning.

“When?” Anke asked softly.

“Soon,” Miller said. “After the afternoon count. Please… please line up as usual.”

“As usual,” Grete echoed. She looked away quickly, as if she didn’t trust her face.

Miller hesitated at the door. “And—” He cleared his throat again. “There’s cornbread too.”

Cornbread meant nothing to most of them. But the way he said it, like a second surprise, made it feel important.

When he left, the sewing room erupted in a controlled storm: questions, speculation, nervous laughter. Someone said they would faint from excitement. Someone else said excitement was foolish. A third said she didn’t care what it was, she would remember the taste forever.

Lotte said nothing. She pressed her fingertips against the fabric in her lap, grounding herself in texture.

She was not a child. She was not easily dazzled.

And yet, her hands trembled.

The line formed early, long before the guards asked for it. Women emerged from barracks as if pulled by an invisible string. They tried to appear casual, but their bodies betrayed them—straight backs too stiff, hands clasped too tightly, eyes darting.

The air near the mess hall smelled different that day.

It wasn’t just the usual steam and starch. There was something else, heavier, richer—oil and spice and a warmth that seemed to sink into the cold air like a promise.

Lotte’s stomach clenched so hard it almost hurt.

Behind her, someone whispered, “I can smell it.”

In front of her, Grete muttered, “Of course you can.”

The doors opened. Guards directed the line in, one by one. The mess hall had been cleaned more than usual; the tables looked less grim, the floors swept. At the far end, a group of American women stood near the serving area—volunteers, their coats still on, faces flushed from work and nerves. They looked at the prisoners with an uncertainty that mirrored the prisoners’ own.

One volunteer, a woman with kind eyes and hair pinned neatly under a hat, clutched a basket like it was something precious. Another had a stack of paper plates. A third held a tray, and even from a distance Lotte saw the gleam of golden crust.

The sight hit her like a wave.

Fried chicken wasn’t just food. It was evidence. Proof that somewhere beyond fences and routines, the world still contained extravagance. Proof that the universe could still offer something unnecessary and beautiful.

As Lotte reached the front, the volunteer with kind eyes smiled hesitantly. “Hello,” she said, voice gentle. She glanced at Miller, who stood nearby, as if checking whether she should speak.

Miller translated. “She says hello.”

Lotte nodded. “Hello.”

The volunteer held out a piece of chicken—thigh or drumstick, Lotte wasn’t sure. The crust was a deep golden brown with darker freckles, like toasted bread. It looked almost unreal.

Lotte took it with both hands. The heat seeped into her palms.

Then a second volunteer placed a square of cornbread on her plate and a small spoonful of something pale and creamy—potato salad, perhaps. Lotte’s plate looked like a painting of abundance.

She stepped aside, heart pounding, and found a seat. Anke sat across from her, staring at her own plate as if it might vanish.

Neither of them spoke for a moment.

Around them, the mess hall filled with a sound Lotte hadn’t heard in months: the hum of anticipation that borders on reverence.

Then Grete sat down hard beside Lotte, and Lotte startled.

“Don’t stare at it,” Grete snapped. “Eat it before you wake up.”

Lotte swallowed. She lifted the piece of chicken toward her face.

The smell was overwhelming—pepper, salt, something smoky, something that reminded her, painfully, of kitchens and Sundays and hands that had once been soft.

Her mouth watered so fiercely she felt ashamed of it.

She took a bite.

The sound was small but distinct: crack.

The crust shattered under her teeth, crisp and thin, giving way to meat that was tender and steaming. Salt and spice flooded her tongue. Fat—real fat, not the thin taste of rationing—coated her mouth in warmth.

For a second, the world went silent.

Then the silence broke, not with laughter, not with shouting, but with something stranger.

A sob.

It came from somewhere to Lotte’s left. A short, sharp intake of breath, followed by the unmistakable tremor of someone trying not to cry. Another sob answered it across the room. Then another.

Lotte looked up and saw women with their hands over their mouths, eyes wide and shining. Some were chewing as tears slid down their cheeks. Others had lowered their faces to their plates, shoulders shaking.

Anke took a bite and froze. Her eyes fluttered closed like a prayer. When she opened them again, they were wet. “Oh,” she whispered, voice cracked. “Oh my God.”

Grete, who had been all sharp edges and warnings, stared at her chicken like it had accused her of something. Then she took a bite, and her jaw tightened. For a moment she looked furious.

And then her face crumpled.

Grete pressed her fist to her mouth and made a sound that was not quite a sob and not quite a laugh. Tears spilled anyway, unstoppable.

Lotte felt something in her chest loosen, like a knot being cut. Without permission, her own eyes filled. She kept chewing, tasting, swallowing, as tears ran down her face and dropped onto her plate.

She didn’t cry because the chicken was “that good,” though it was. She cried because the taste carried a message her body understood before her mind did:

You are still alive. You can still feel pleasure. You can still be surprised.

It was not just food. It was a door opening, briefly, to a life that felt impossibly far away.

Across the mess hall, one of the volunteers watched, eyes wide with shock. She whispered to another, and they both looked stricken—as if they had wanted to offer comfort and instead had accidentally uncovered a wound.

Miller moved toward them, speaking quietly. The volunteer with kind eyes wiped her own eyes with the back of her glove.

Lotte wanted to tell her: It’s not your fault. She wanted to tell her: This is kindness, and kindness hurts when you haven’t had it in a long time.

But her throat was too tight.

Around her, women ate like they were afraid the food might evaporate. Not frantic, not animal-like, but with an intensity that made every bite feel ceremonial. Some murmured to each other in broken sentences:

“I forgot—”

“I can’t—”

“It tastes like—”

“My mother—”

“Please don’t take it—”

A woman at the next table laughed suddenly, a bright burst that sounded almost wild. “We couldn’t stop eating,” she said in German, breathless, half-crying. “Even if we wanted to, we couldn’t!”

Someone else answered, “I don’t want to stop.”

Then, from the far end of the hall, a guard called out gently, “Easy. There’s enough.”

Enough.

The word felt like a miracle.

After the meal, the compound buzzed the way it might have after a festival in another life. Women returned to their barracks holding the memory on their tongues, shaking their heads as if trying to convince themselves it had happened.

Outside, the sky had turned softer, the late afternoon sun lowering like a warm hand.

Lotte sat on the steps of the barracks with Anke. Neither of them spoke at first. The air between them felt newly fragile.

Finally Anke said, “I hated that I cried.”

Lotte looked at her. “Why?”

Anke swallowed. “Because it felt… weak.”

Lotte thought about Grete’s face when it crumpled, the way her tears seemed torn from a place she’d kept locked. “I don’t think it was weakness,” Lotte said slowly. “I think it was… memory.”

Anke let out a humorless laugh. “Memory tastes like pepper and oil?”

“Memory tastes like everything,” Lotte replied. “It tastes like what you miss.”

Anke stared at the yard where women walked in small groups, talking animatedly. “When I bit into it,” she said, voice low, “I remembered sitting in my father’s kitchen before everything changed. He used to come home with a little paper packet of sausages. We’d eat them standing up because he said sitting was too slow.”

Lotte nodded. She could see it, vivid as a photograph.

“And then,” Anke continued, “I remembered other things too. The things I try not to remember. The hunger. The cold. The fear. It all came rushing back because my body suddenly remembered what not being hungry felt like.”

Lotte felt her own throat tighten again. She stared down at her hands. They were still the same hands, still roughened by work. But for a moment today, they had held something warm and unnecessary.

“Do you think they meant it like this?” Lotte asked quietly. “Do you think they knew what it would do?”

Anke shook her head. “How could they?”

They sat in silence until footsteps approached. Grete appeared, arms folded, eyes red but face composed as if she’d rebuilt her walls brick by brick.

She looked down at them. “You two look like mourners,” she said, but her voice lacked its usual bite.

Anke lifted her chin. “Maybe we are.”

Grete huffed and sat down beside Lotte, a little too close. For a while she said nothing, staring out at the fence line. Then she spoke without looking at them.

“When I was a girl,” she said, “my grandmother would fry chicken for harvest time. We didn’t have it often. Oil was precious even then. But she’d save, and when the day came, she’d stand at the stove like a queen.”

Lotte turned to her. Grete’s eyes were fixed on the distance, but her voice had softened into something almost tender.

“The smell would fill the house,” Grete continued. “And we would all pretend we weren’t impatient, but we were. And when she finally put the plate down, my grandfather would say, ‘Now, this is living.’”

Grete’s mouth tightened. “Today, when I bit into that American chicken, I heard my grandfather’s voice.”

Anke’s eyes widened slightly.

Grete’s jaw worked, as if she was chewing words. “I didn’t cry because of the chicken. I cried because—” She exhaled sharply. “Because I realized I might never hear that voice again. And because it came back so clearly I thought I’d gone mad.”

Lotte reached out without thinking and put her hand on Grete’s sleeve. Grete stiffened, then—after a moment—did not pull away.

The three of them sat there as the sun lowered, each carrying a private storm.

That evening, the volunteers returned.

Not with food this time, but with something else: a small stack of cards. Miller called a few women over to translate.

The cards were plain, with a simple message printed on them in English and German:

We hope this meal brought you comfort. We know we cannot understand everything you have endured, but we wish you warmth and peace.

It was not a grand political statement. It did not erase fences. It did not change the past.

But it was an acknowledgment—one human to another—that suffering existed, and that kindness could still be offered without conditions.

Lotte held the card in her hands for a long time.

“What will you do with it?” Anke asked.

“I don’t know,” Lotte admitted. “Keep it. Hide it. Read it when I forget the world can be gentle.”

Grete snorted softly. “The world is not gentle.”

“No,” Lotte agreed. “But people can be.”

Grete looked at her sharply, then away. “Don’t get sentimental,” she muttered, but her voice lacked conviction.

Later, when the lights went out and the barracks settled into darkness, Lotte lay on her bunk and listened to the familiar night sounds.

But something had changed.

The camp was still the camp. The fences were still there. The uncertainty still waited beyond sleep. Yet the taste of fried chicken lingered, stubborn as hope, and with it came a strange new understanding:

Even in a place designed to reduce people to routines and numbers, a single unexpected kindness could restore a piece of the self.

Not forever. Not perfectly.

But enough to remind them they were not only prisoners of circumstance. They were women with memories, with grief, with hunger for more than food.

Before sleep claimed her, Lotte heard a quiet voice from somewhere in the dark—someone whispering to no one in particular, as if saying it out loud would keep it real.

“We couldn’t stop eating,” the voice said, half-laughing through tears. “And for the first time in so long… I didn’t want to stop living.”

Lotte closed her eyes and let that sentence settle into her chest like a warm ember.

Outside, the wind moved through the wire, making it sing a thin, metallic song.

Inside, in the fragile space between sorrow and tomorrow, something simple and golden had left its mark—proof that even the smallest taste of warmth could break open the hardest hearts, and that sometimes, tears were not a sign of weakness at all.

Sometimes, they were the sound of a soul remembering how to feel.