They Arrived in Oklahoma as “German Child Soldiers,” But When the War Ended They Refused to Go Home—Then a Locked Trunk, a Whispered Oath, and a Missing Name Changed Everything Overnight

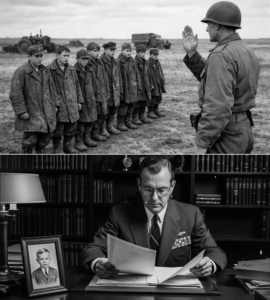

The first time I saw them, they were standing in a line that looked too straight for boys and too quiet for men.

Oklahoma had an honest way of showing you who you were—wind that peeled secrets off your face, sunlight that didn’t flatter, dust that got into everything you thought you’d sealed. That afternoon in late September of 1945, the wind cut across the flat land behind Fort Reno and dragged the smell of dry grass through the camp fences.

“New group,” Captain Rourke said, squinting like the sun had personally offended him. “You speak German, right, Carter?”

“I read it better than I speak it,” I admitted.

“You’ll speak it fine today,” he said, and handed me a clipboard like it could transfer confidence through wood pulp. “They’re… unusual.”

He didn’t say the phrase everyone else used. German child soldiers. The newspaper man who’d bribed his way to the gate called them that. A cook behind the mess hall muttered it like a curse. Even the guards—hard men who’d watched thousands of prisoners shuffle through—said it in a lowered voice, as if naming the thing gave it weight.

The boys wore uniforms that didn’t fit right. Sleeves too long, collars too tight, boots scuffed and borrowed. Their faces had that hollowed, watchful look I’d seen in old men in breadlines, except these faces still held the last stubborn hints of youth—freckles that didn’t match the seriousness in their eyes, a smear of dirt where a tear had dried.

They were thin in the way that made you angry at the world, not at them.

I stepped forward, clipboard under my arm, and said, in careful German, “I’m Thomas Carter. I’m here to help with paperwork.”

No one answered. They stared straight ahead, hands at their sides, like statues with ribs.

Then a boy near the middle moved his lips without raising his voice. “We are not prisoners,” he said. His accent was northern, the words crisp. “We are… detained guests.”

That made Captain Rourke bark a laugh. “Detained guests,” he repeated in English, as if tasting something sour. “Tell him it’s a camp. And the war’s over.”

I translated the second part and left the first part alone.

The boy’s eyes flicked to me. Gray eyes, clear as a winter creek. He looked at my face like he was measuring it for a mask.

“The war is over,” he repeated. “That is why we need to talk.”

The group behind him murmured—just a breath of sound, like grass leaning.

I had done this work for a year. I’d interviewed German prisoners who’d surrendered in North Africa, men from U-boats who’d come up half-frozen, officers who thought their rank could outrun our rules. I’d seen arrogance and resignation and fear.

I had not seen this: a line of boys who looked like they’d rehearsed being silent.

Captain Rourke led us through the administrative building. Inside, the air smelled like old coffee and ink. A fan turned lazily in the ceiling, more decoration than relief. We sat them on benches. One of the guards offered water, and the boys accepted like it was a test—each taking exactly one sip, each placing the cups down at the same angle.

“What’s your unit?” I asked in German, moving through the forms. “Name, age, place of birth.”

Silence again.

Then the gray-eyed boy spoke, but not to answer. “Are you from Oklahoma?”

“No,” I said. “Illinois.”

He nodded, as if that explained something. “Then you understand what it is to leave a place and find another.”

That wasn’t a normal response to a normal question.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

The boy’s gaze went to the window. Beyond the glass, the fence shimmered in heat. “Karl,” he said finally. “Karl Voss.”

“Age?”

He paused. “Sixteen.”

The pencil stopped on my paper.

Sixteen. I looked at the others. Another boy might have been fifteen, maybe fourteen. A few could have passed for eighteen if you didn’t look too long. But there were no men with them. No officers. No fathers. Just boys, and the weight they carried like invisible packs.

“Why are you here?” I asked, and before Captain Rourke could object, I added, “Not the official reason. The real one.”

Karl’s eyes returned to me. “Because we were told to wait,” he said. “And then no one came.”

Captain Rourke leaned forward in his chair. “Tell them repatriation’s coming,” he said. “Ships are being arranged. We’re not keeping them here.”

I translated. Karl’s expression didn’t change.

“No,” he said, with gentle certainty. “We are not leaving.”

The room went quiet in a way that made my ears ring.

Rourke’s jaw tightened. “They don’t get to decide that.”

Karl looked at the captain, even though he didn’t understand English. “There are reasons,” he said to me, as if the captain wasn’t there at all. “Important reasons.”

“Like what?” I asked.

Karl’s fingers curled once, almost imperceptibly. “A promise,” he said. “And something hidden.”

Rourke slapped the clipboard from my hand onto the desk. “Enough. You tell him this isn’t a choice. War’s done. They go home. Germany needs bodies to rebuild. They’ll be lucky to have a country left to return to.”

I translated the part about going home. I softened the rest. I had learned that words could break people faster than hunger.

Karl listened politely, like a student taking notes. When I finished, he said, “May we speak privately?”

Captain Rourke snorted. “No.”

Karl’s eyes remained on me. “Please,” he said. “It is for your country too.”

That was the first time that day I felt the prickle of something that wasn’t pity.

It was curiosity—sharp and unwelcome.

That night, I couldn’t sleep.

The barracks where the interpreters stayed sat on the edge of the camp grounds, far enough from the prisoner compound that you could pretend you weren’t part of it. I lay on my bunk, the thin mattress pressing springs into my ribs, and listened to the wind push against the building like an impatient hand.

Somewhere out beyond the fence, coyotes yipped. Somewhere closer, a guard’s boots crunched gravel as he walked his route. The camp was full of movement that wasn’t going anywhere.

I kept seeing Karl’s face when he said, We are not leaving.

Not defiance. Not drama. Just… decision.

At dawn, I went to the office early, hoping to catch Captain Rourke before he got dug into his own stubbornness. The building was still cool, the air smelling faintly of yesterday’s paper.

Rourke was already there, shirt sleeves rolled up, coffee in hand. “Carter,” he said, like my name had been waiting on his tongue.

“About the boys,” I began.

“They’re being processed like everyone else,” he said, cutting me off. “And they’ll be on the list for repatriation. End of story.”

“Sir,” I said carefully, “they’re… not like the others.”

Rourke’s eyes narrowed. “They’re prisoners. That’s like enough.”

“They said they have something hidden,” I pressed. “And that it involves our country.”

He stared at me for a long beat, then looked down into his coffee like it held the answer. “You ever hear the phrase ‘a drowning man grabs anything’?”

“Yes, sir.”

“They’re drowning,” he said. “Home’s rubble. They’re scared. So they’ll say anything.”

Maybe he was right. But the memory of those boys placing cups down at the same angle wouldn’t leave me.

“Let me talk to them again,” I said. “Ten minutes. If it’s nonsense, I’ll tell you.”

Rourke exhaled like he was pushing smoke out of his lungs. “Fine,” he said. “Ten minutes. And if they start spinning fairy tales, you shut it down.”

He scribbled something on a slip of paper—a pass—and shoved it at me. “Bring a guard,” he added. “No hero stuff.”

I walked to the compound with Sergeant Miller, who chewed toothpicks like it was a hobby.

“You really think those kids got some big secret?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said.

Miller shrugged. “Kids got secrets. Usually it’s where they stole pies from.”

The boys were in a smaller barrack separated from the main prisoner population. That detail alone said someone in command had already decided they were different. The guard at the door let us in without a word.

Inside, the air was cleaner than I expected. The bunks were made. Boots lined up. No one spoke. They sat on their beds like they’d been summoned for inspection.

Karl stood when I entered. “Mr. Carter,” he said softly.

“It’s Thomas,” I said, then realized how strange it was to offer a first name in a place where names were reduced to numbers.

He nodded anyway. “Thomas,” he repeated, like he was trying the sound in his mouth.

I motioned toward the corner, away from the others. Sergeant Miller leaned against the wall, arms crossed, watching like a man at a county fair.

“Tell me,” I said in German, lowering my voice. “Why won’t you leave?”

Karl glanced at the other boys. Then he spoke quickly, like he’d been holding the words behind his teeth. “If we return, we disappear,” he said.

“You mean… in the chaos?” I asked.

Karl’s jaw tightened. “In the sorting,” he said. “The questions. The blame. The people who will need someone to punish.”

I had read enough reports to understand. I didn’t need him to say more.

“And the promise?” I asked.

Karl hesitated, then reached under his thin mattress. For a moment my heart jumped—an old reflex in a camp—but what he pulled out wasn’t a weapon.

It was a small, battered trunk latch. Just the metal latch, snapped from whatever it had been attached to. He held it like a relic.

“This is from a trunk,” he said.

“Yes,” I said, confused.

“A trunk that is not here,” Karl continued. “A trunk that belongs to an American.”

The word American landed like a stone.

Sergeant Miller shifted, his boots scuffing the floor. “What’re they saying?” he asked.

Karl ignored him, still speaking to me. “In April,” he said, “we were moved west. Not to fight. To carry things. Supplies. Papers. We were told to obey and not ask questions.”

“What things?” I asked.

Karl swallowed. “A trunk,” he said. “A heavy trunk with a lock. Marked with a name in paint—English letters.”

“What name?”

Karl’s eyes flicked up, and I saw something like fear, real fear, for the first time. “We were told not to speak it,” he said. “But we memorized it anyway.”

I leaned closer. “Karl,” I said, “what name?”

He took a breath. “Hollis.” He pronounced it carefully.

Something shifted in my mind. I had seen that name on a missing personnel list, tucked in a folder that Captain Rourke kept in his top drawer. The folder that came out only when a family wrote too many letters.

I turned my head slightly. “Sergeant,” I said in English, “do we have any missing airmen named Hollis?”

Miller frowned. “Hollis… Hollis…” He snapped his fingers. “Yeah. There was a pilot. Went down somewhere near the state line—Texas, maybe. Rumor was he bailed out. Never found.”

Karl watched my face, reading my reaction even without understanding the words.

“The trunk,” Karl said quietly, “was buried.”

“Where?” I asked, the question coming out too fast.

Karl held up the latch. “We broke it,” he said. “Not on purpose. It fell from the truck when we were crossing a bridge. A small bridge. Wooden. There was a creek under it.”

He looked around the barrack, then lowered his voice further. “We knew we would not survive the journey,” he said. “So we made a pact. If any of us lived… we would find someone who could return the trunk.”

“To the pilot?” I asked.

Karl nodded. “Or to his family,” he said. “Because the trunk was not… ordinary.”

“What do you mean?”

Karl’s mouth tightened. “It made the men who guarded it afraid,” he said. “We saw it in their faces.”

Sergeant Miller pushed off the wall. “Alright,” he said. “That’s enough. You’re done, Carter.”

I looked at him, then back to Karl. “Why refuse to go home?” I asked, forcing myself to finish the thread. “You could tell this story in Germany to our officials there.”

Karl’s lips pressed together. “No one would listen,” he said. “Or they would listen and take it and we would still disappear. Here,” he said, and his eyes swept the room—the bunks, the fence outside, the guard—“here there is order. Here there are papers. Here promises can be written and kept.”

It was a strange thing to hear from a boy who’d been on the enemy’s side.

Karl lifted the latch slightly. “We kept our promise,” he said. “Now you must keep yours.”

“I didn’t make a promise,” I said, though my voice lacked conviction.

Karl’s gaze didn’t waver. “You are America,” he said simply. “You can decide what America does.”

Sergeant Miller grabbed my elbow. “We’re leaving,” he said.

As he pulled me toward the door, I looked back at Karl. The boy didn’t follow. He didn’t plead. He simply stood there, latch in his hand, waiting like someone who had already endured the worst and had no patience for theater.

Outside, the sun hit me like a slap.

Miller exhaled hard. “You buying that?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said again, but this time the words felt weaker.

Miller squinted toward the administrative building. “Even if it’s true,” he said, “it’s above our pay.”

Maybe. But the name Hollis wouldn’t stop echoing.

Captain Rourke didn’t like surprises. I knew that before I knocked on his office door, and I knew it again when he looked up and saw my face.

“What is it?” he asked.

I told him. Not everything. Not Karl’s fear about disappearing. Not the way those boys held themselves like they’d practiced being brave. I told him the measurable things: a trunk, a name, a creek, a broken latch.

Rourke listened without interrupting, which in itself felt like a shift in gravity.

When I finished, he reached into his drawer and pulled out the folder. The missing personnel list was inside, typed in neat rows. He traced a finger down it.

“Hollis,” he murmured. “Lieutenant James Hollis. Flight out of Tinker. Lost June ’44.”

He leaned back, eyes narrowing. “If they’re lying,” he said, “it’s a sick lie.”

“I don’t think they are,” I said.

Rourke stared at me for a long moment, then stood. “Get Miller,” he said. “And a truck.”

My heart thudded. “Sir—”

“And Carter,” he added, grabbing his hat, “if this turns out to be some kind of stunt, I’m assigning you to inventory latrines until 1950.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, and felt strangely grateful for the threat—it meant we were moving.

We drove west out of the camp, the truck rattling over uneven road. The landscape unfolded in gold and brown, fields patched with scrub and fence lines. It was hard to imagine that war could reach this far, and yet it had, in quiet ways—ration lines, telegrams, missing names.

Karl sat in the back with two guards. He didn’t speak unless spoken to. He held the latch in his lap like a compass.

After an hour, he told us to turn onto a dirt road that disappeared between stands of cottonwood. The truck bumped and swayed. Miller cursed under his breath. Captain Rourke kept his eyes forward, jaw set.

Finally, Karl raised a hand. “Stop,” he said.

We climbed out. The air smelled like mud and leaves. A narrow creek ran under a sagging wooden bridge, water dark in the shade. The boards creaked when we stepped on them.

Karl pointed to the bank downstream, where the earth was soft and thick with roots.

“Here,” he said.

Rourke motioned to the guards. Shovels came out. Dirt flew. The boys stood back, faces unreadable. I watched Karl’s hands. They were clenched so tight his knuckles went white.

After twenty minutes, one of the guards hit something solid.

A sound like metal against metal rang out, sharp and undeniable.

Rourke leaned down, digging with his own hands now, impatience breaking through his control. The earth gave way.

A corner emerged—wood, darkened by time and water, bound with rusted straps.

The trunk.

Everyone froze.

Rourke looked at me. For the first time since I’d met him, his expression held something like awe. “Well,” he said quietly. “I’ll be damned.”

They hauled the trunk out, mud dripping off it. The lock was broken, just as Karl said. The name painted on the top was faint but visible.

HOLLIS.

Karl exhaled as if he’d been holding his breath since April.

Rourke wiped his hands on his pants. “Open it,” he said.

One guard pried the lid. The hinges groaned.

Inside were papers wrapped in oilcloth. Not just one bundle—several. There was also a small leather notebook, swollen from moisture but intact.

Rourke’s face hardened, professional again. “This goes straight to intelligence,” he said. “Carter, you don’t discuss this. Miller, you don’t even think about it.”

Miller raised his hands. “I ain’t thinking about nothing, sir.”

Karl stared at the trunk, eyes wide. “We kept it safe,” he whispered in German. “We kept it safe.”

I looked at him. “Why?” I asked. “Why risk it?”

Karl’s gaze moved to the creek, to the bridge, to the sky beyond. “Because,” he said, “some things must be returned, or the world stays broken.”

For a moment, no one spoke. The wind rustled the cottonwood leaves, making a sound like distant applause.

Then Karl turned to Captain Rourke and said something in German that I hadn’t expected.

“Now,” he said, “we have done what you would call… our part.”

Rourke looked at me. “What’d he say?”

I swallowed. “He said,” I began, choosing words carefully, “that they’ve kept their end of a bargain.”

Rourke stared at Karl, then at the boys behind him. Sixteen, fifteen, maybe fourteen. Faces that had seen too much.

“And what do they want?” Rourke asked.

Karl answered me directly. “We want papers,” he said. “We want work. We want to stay.”

The sentence hung between us like smoke.

Rourke’s voice came rough. “Tell him that’s not how it works.”

I translated.

Karl didn’t flinch. He nodded as if he’d expected resistance. “Then,” he said, “tell him we will wait. We are good at waiting.”

Back at Fort Reno, the trunk disappeared behind locked doors and official stamps. Men in suits arrived the next day, faces smooth and eyes sharp. They asked questions that made the air feel thin. They thanked no one.

The boys were moved again—this time to a quieter section of the compound. Captain Rourke didn’t look at me the same way after that. Not kinder. Not softer. Just… more careful, like he realized the world could still surprise him.

Two weeks later, a letter came from Washington with words that sounded like they’d been ironed flat: special consideration. case-by-case review. temporary labor placement. pending final decision.

It wasn’t freedom, but it wasn’t a ship ticket either.

Karl read the translated summary in silence, then looked up at me. “So,” he said, “we are still here.”

“For now,” I said.

He nodded. “For now is better than never,” he replied, and there was no triumph in it—only relief.

In the months that followed, the boys worked on nearby farms under supervision, their uniforms replaced by borrowed overalls and patched shirts. Some townspeople refused to look at them. Others offered cautious nods. A few women left extra biscuits on porch railings without saying who they were for.

Life, as it always does, found a way to push forward.

But the mystery never fully left.

One evening, near Christmas, I found Karl standing by the fence, staring out at the open land beyond. The sky was bruised purple with dusk.

“Do you miss home?” I asked.

Karl’s breath made a small cloud. “I miss the idea of it,” he said. “Not the ruins.”

“You could still go back someday,” I offered.

He looked at me, gray eyes steady. “And you?” he asked. “Will you forget us?”

I didn’t know how to answer that. It felt like too big a question for a fence line.

“I’ll remember,” I said finally.

Karl nodded, accepting it like a contract.

Then he did something that startled me. He reached into his pocket and pulled out the trunk latch—the same battered piece of metal. I’d assumed it had been taken as evidence, filed away.

“I kept it,” he said, and held it out to me.

“I can’t take that,” I said automatically.

“You must,” Karl insisted. “So you remember that we were not only what the war made us.”

I hesitated, then took it. It was cold, heavier than it looked.

Karl’s shoulders eased, just slightly, as if a burden had shifted from him to me. “Promises,” he said softly, “are the only things that survive.”

Behind us, the camp lights flickered on, throwing long shadows across the ground. The wind rose again, sweeping over Oklahoma like a living thing.

Karl looked out beyond the fence one last time and said, so quietly I almost missed it, “We refused to leave because we were tired of being carried by other people’s decisions.”

He turned and walked back toward the barracks, footsteps steady on gravel.

I stood alone at the fence, the latch in my palm, and realized something that made my throat tighten:

The war might have ended on paper, but for some people—especially the ones who’d been young enough to be shaped by it—it didn’t end with a parade or a treaty.

Sometimes it ended with a locked trunk in a creek bed.

Sometimes it ended with a boy deciding, for the first time, to choose his own tomorrow.

And sometimes, if you were unlucky, it ended with a promise placed in your hand—cold metal and quiet weight—so you’d never be able to pretend you hadn’t seen what the world could do… and what it could still repair.