The US Had No CV Joints in 1940 — So Bendix Built ‘Rolling Balls’ to Save the Jeep

September 23, 1940, Camp Holird, Maryland. The American Bansom BRC prototype designed by Carl Props in just 5 days sat motionless in the Army test yard despite working perfectly during initial trials. The problem wasn’t the vehicle itself. The 65-in wheelbase roadster had exceeded every performance specification the Army had demanded.

It climbed 60% grades, forted water 18 in deep, and weighed just 1,840 lb despite the Army’s, 1270lb target being impossible. The problem was that Bantham couldn’t get parts to build more. Specifically, constant velocity joints, these specialized connectors that allowed front wheels to both steer and drive simultaneously without vibration.

Simple universal joints used in rearwheel drive vehicles for decades caused violent whipping in the steering wheel when front wheels turned while driving. Front-wheel drive vehicles absolutely required CV joints. And America’s only supplier, Spicer Manufacturing told the Army they wouldn’t gear up for CV joint production unless they received orders for at least 1,500 vehicles.

The tiny BANM company awarded a contract for just 70 prototypes couldn’t meet that threshold. The Quartermaster Corps faced a crisis. They’d found the perfect reconnaissance vehicle, but the technology to mass-produce it didn’t exist in America. The solution would come from an unlikely source, Bendix Corporation, better known for brakes and carburetors, who would adapt a German-designed rolling ball constant velocity joint that used five steel spheres to transmit power smoothly around corners.

This is the documented story of how American industry, facing a technological gap in 1940, created the specialized joints that made four-wheel drive practical. not just saving the Jeep, but launching an entire category of vehicles that dominates roads today. To understand why CV joints were critical, we need to understand what happens when a shaft must both rotate and change angles simultaneously.

In a rearwheel drive vehicle, the drive shaft connects the transmission to the rear axle in a straight line or nearly straight. A simple Cardon cross universal joint, also called a Spicer joint after Clarence Spicer, who patented it in 1904, works perfectly. Two yolks connected by a cross-shaped piece riding in four needle bearings.

But Cardon joints have a fundamental problem. They’re not constant velocity. When the driving and driven shafts are at an angle, the output shaft speeds up and slows down twice per revolution. At small angles, 5 to 10 degrees, this pulsation is barely noticeable. At larger angles, 30 plus degrees, the vibration becomes severe.

For rear axles, this doesn’t matter. The axle doesn’t change angle during operation. But front wheels must steer, creating continuously variable angles between the drive shaft and wheel hub. If you use simple universal joints on driven front wheels, the pulsation creates violent vibration in the steering wheel, making the vehicle nearly uncontrollable.

French engineer Pierre Fay had solved this in the 1920s with his tractor joint used in the pioneering tracta front-wheel drive sports cars. German engineer Alfred Razeppa invented another solution in 1926, a ball and cage design used in DKW front-wheel drive cars starting 1929. But in 1940, American manufacturers had virtually no experience with these technologies.

Front-wheel drive was exotic, used primarily in European sports cars and experimental vehicles. American industry would need to learn fast. On June 6th, 1940, Lieutenant Colonel William Lee of the US Army Infantry and Harry Payne, Banttom’s Washington lobbyist, met to outline specifications for a lightweight reconnaissance vehicle.

Lee had observed German Cuba wagon vehicles in action during the Battle of France and wanted American equivalents immediately. The specifications they drafted were brutal. Weight maximum 1,270 lb. Wheelbase 80 in or less. Engine minimum 40 horsepower. Ground clearance 6.25 in. Four-wheel drive with twospeed transfer case.

Foring depth 18 in minimum. Payload 600 lb. Driver plus three passengers plus equipment. On July 11th, 1940, the quartermaster corps sent invitations to 134 manufacturers requesting bids for 70 prototype vehicles. The deadline, 49 days from contract award to delivery of working prototype. Only three companies responded seriously.

American Banttom Car Company, Butler, Pennsylvania, Willy’s Overland Motors, Toledo, Ohio, and Ford Motor Company, Dearbornne, Michigan. Banttom, despite being the smallest and most financially troubled, got the first contract on July 17th, 1940. Designer Carl Propes worked around the clock, completing detailed engineering drawings in five days, an achievement considered impossible by automotive standards.

The Bansom BRC rolled out September 21, 1940 and immediately impressed testers. But Bansom’s tiny size and weak finances raised Army doubts about production capacity. More critically, there was the CV joint problem. Spicer Manufacturing Company inToledo, Ohio was America’s dominant universal joint manufacturer. Founded by Clarence Spicer in 1904, the company had pioneered automotive driveline technology.

By 1940, Spicer produced millions of card and cross universal joints annually for rearwheel drive vehicles. But they had only limited experience with constant velocity joints, the sophisticated bearings required for front-wheel drive. When Bantam asked Spicer to supply CV joints, Spicer’s response was blunt. We need minimum orders of 1,500 units to justify tooling costs for CV joint production.

Banam’s 70UN prototype contract didn’t come close. The army frustrated invited Willys and Ford to build competing prototypes promising large production contracts to whoever won. This guaranteed sufficient volume to interest suppliers. Willy’s quad appeared November 13th, 1940, 2,453 lb.

Nearly 300 lb overweight, but with a powerful 60 horsepower goevil engine that outperformed competitors. Ford Pygmy, later GP for government 80inch wheelbase, appeared November 23rd, 1940. Lighter than Willys at 2,150 lbs, but using Ford’s tractor derived engine. All three vehicles faced the same problem. America lacked domestic CV joint production capability.

Spicer could supply limited quantities for testing, but couldn’t scale to the thousands of vehicles per month the Army projected needing. The solution required developing American versions of European CV joint designs and doing it fast. As the Army standardized the Jeep design, combining best features from all three prototypes, and prepared for mass production, three different CV joint technologies competed.

One, the Repza joint, Ford’s choice. Alfred H. Repsa, a German American engineer working for mechanics universal joint division, later Rockwell Standard, had patented his ball and cage CV joint design in the United States in the 1920s. The Repza joint used six steel balls held in a cage between inner and outer races, similar to a ball bearing.

The balls rolled in curved grooves machined into both races. As the joint articulated, the cage maintained the balls in the homokinetic plane, the geometric plane that bisects the angle between input and output shafts. This ensured constant velocity, no speed variation regardless of joint angle.

Ford with its massive engineering resources and existing relationship with Rockwell adopted repsa joints for Ford GP and GPW government willies pattern Jeeps. The Repza was mechanically elegant but expensive to manufacture requiring precision machining of spherical races and individually matched components. Two, the tracta joint occasional use.

The tractor joint designed by Pierre Fenel in the 1920s used a different principle. Two semicherical sliding pieces, one male and one female that interlocked in a floating connection. Each yolk engaged circular grooves on intermediate members coupled by tongue and groove joints. As angles changed, the intermediate members accelerated and decelerated, but the design maintained constant average velocity.

French military vehicles Laughafle and Panhard and British Alvis and Dameler Scout cars used them extensively. Some early American jeeps used track the joints likely sourced from British or French suppliers under lend lease arrangements, but they weren’t suitable for high volume American production. The design was controlled by French patents and manufacturing techniques weren’t fully understood by American industry.

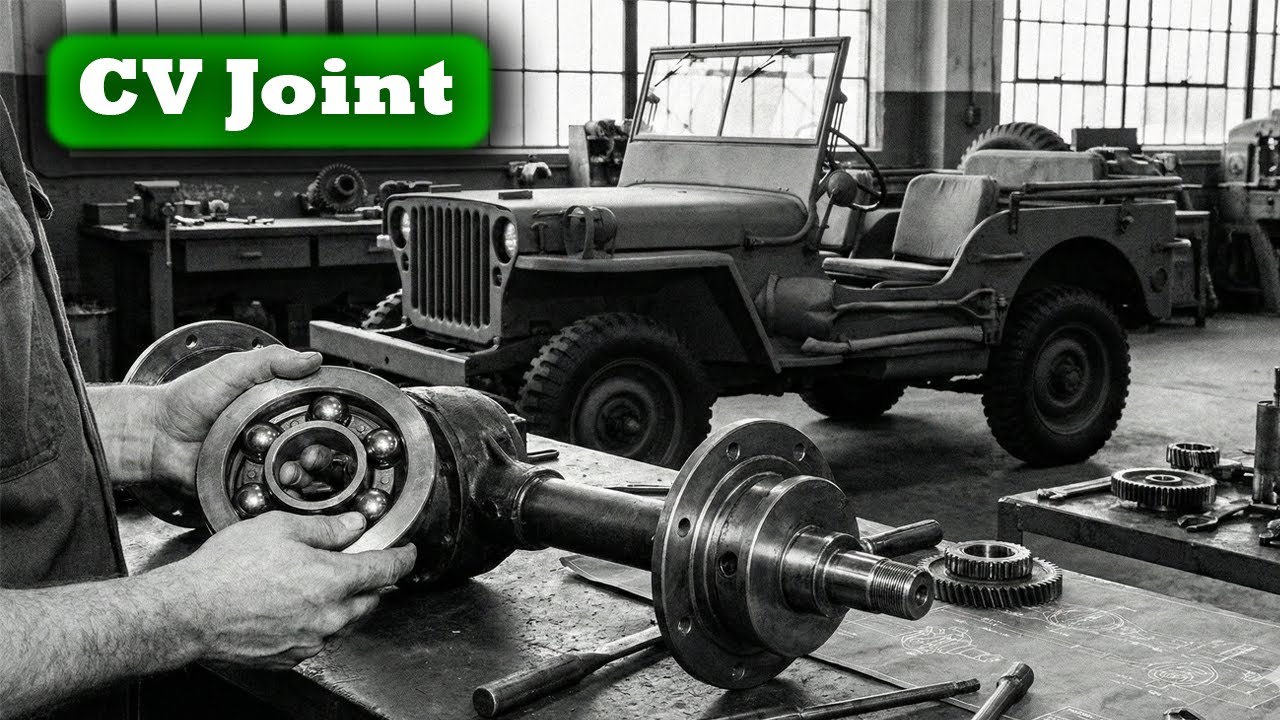

Three, the Bendix Weiss joint Willie Solution. Bendix Aviation Corporation, primarily known for brakes, carburetors, and aircraft components, entered CV joint manufacturing through an acquisition of rights to the Weiss joint, another German design. The Bendix Weiss joint used five steel balls, four outer balls transmitting torque, plus one center ball that locked the outer balls in position and maintained proper geometry.

Unlike Repza’s cage design, Bendix Weiss balls were a tight fit between two yolk halves with no separate cage. The center ball rotated on a pin inserted in the outer race. When shafts aligned 180° angle, balls sat in a plane perpendicular to the shafts. When driven shaft moved, creating angle, balls moved half the angular distance, automatically maintaining the homokinetic plane through pure geometry.

Example, if the driven shaft moved 20°, reducing the shaft angle to 160°, the balls moved 10°. The angle between driving shaft and ball plane remained 90° minus half the shaft angle, automatically constant velocity. Willy’s Overland, producing the bulk of military jeeps, designated MB, adopted Bendix Whites joints as standard.

The design was robust, relatively simple to manufacture, and didn’t require the precision machining of reps joints. Between 1941 and 1945, American industry produced approximately 640,000 military jeeps. Willies MB about 360,000 units. Ford GPW about 280,000 units. Every single one required two CV joints, one for each front wheel.

That meant American manufacturers had to produceroughly 1.3 million CV joints during the war. More constant velocity joints than had been manufactured in the entire pre-war world. Bendix Corporation became the primary supplier for Willys MB. Their Toledo plant expanded rapidly in 1941 1942 produced Bendix Weiss joints by the tens of thousands monthly.

The manufacturing process, one forging yolks. The input and output shaft yolks were drop forged from highcarbon steel, then machined to precise dimensions. Two, grinding races. The curved grooves or races that guided the balls had to be ground to precise radi and surface finish. Any imperfection would cause binding or premature wear.

Three, ball production. The five steel balls, four outer, one center, were manufactured to tight tolerances, typically within 0.001 in diameter variation. Then they were hardened through heat treatment and precision ground. Four, pin manufacturing. The sensor pin that held the locking ball required precise positioning and heat treatment.

Five, assembly. Components were assembled with specific grease lubricants, then sealed with rubber boots to prevent contamination. And six, quality control. Each joint was rotated through full range of motion, checked for smooth operation, and absence of binding. Defective units were scrapped or reworked.

The production rates were extraordinary. By 1943, Bendix’s Toledo facility produced CV joints at rates exceeding 30,000 per month. An entire month’s output would have supplied global pre-war demand for years. The CV joints faced their first serious test in North Africa, where American forces landed in Operation Torch November 1942. Sergeant Mike Daly, a maintenance technician with the First Armored Division, later recalled the brutal conditions.

The sand got into everything. We disassembled CV joint boots weekly to repack them with grease. The Bendix joints held up better than we expected. The five ball design was simple enough that even when contaminated, they kept working. We had more problems with wheel bearings than CV joints. The rubber boots protecting CV joints from dirt and retaining lubricating grease were vulnerable points.

Tears in boots allowed sand infiltration causing rapid wear. But even contaminated Bendix Weiss joints often continued functioning. The tight fitting balls and simple geometry meant the joint could tolerate some debris without complete failure. In European operations, 1944 and 1945, Jeeps faced different challenges. deep mud, snow, and extreme cold.

Corporal James McCarthy, 1001st Airborne Division, described CV joint performance at Baston, December 1944. Temperature hit -20° F. Everything froze. Batteries died, oil thickened, hydraulics locked, but the Jeeps kept running. The CV joints packed with cold weather grease worked fine even when the boots cracked from cold.

We’d warm engines with fires underneath, change oil, and keep moving. The CV joints robustness stemmed partly from design simplicity. Unlike complex ball and cage resipa joints with many precisely fitted parts, Bendix Weiss joints had just seven components. Two yolks, four balls, one center ball, one pin.

Fewer parts meant fewer failure modes. CV joints faced their most extreme test in Pacific amphibious landings where jeeps had to operate immersed in seawater. During the Philippines campaign 1944 1945, Jeeps routinely drove through shallow water during beach landings. Salt water is catastrophically destructive to steel bearings.

It penetrates seals, corrods metal, and destroys lubricants. Technical Sergeant Robert Chen, 96 Infantry Division, described CV Joint Maintenance after the Lee landing, October 1944. We’d weighed Jeeps through waste deep water to get ashore. First thing after landing, drain and repack every CV joint, wheelbearing, and differential. The rubber boots would be full of seawater mixed with grease, nasty brown slime.

We’d clean everything, repack with fresh grease, replace torn boots. The Bendix joints, once repacked, worked fine, but if you didn’t maintain them after saltwater exposure, they’d seize within days. Rust would lock the balls to the yolks. The Pacific experience drove improvements in boot design and sealing. By 1944, improved rubber compounds and reinforced boot attachments increased saltwater resistance. But no seal is perfect.

Regular maintenance remained essential. When World War II ended, Willy’s Overland recognized commercial potential in their military Jeep. The CJ2A, civilian Jeep 2A launched in 1945, becoming the world’s first mass-produced civilian four-wheel drive vehicle. The CJ2A retained military MB components, including Bendix Weiss CV joints in the front axle.

This made the civilian Jeep expensive compared to conventional vehicles. CV joints cost more than simple universal joints, but it enabled capabilities no other civilian vehicle offered. Farmers, ranchers, construction companies, and outdoors enthusiasts bought CJs by the thousands. The vehicles established four-wheel drive aspractical for civilian use, not just military.

But the CV joint revolution went far beyond Jeeps. Land Rover launched in Britain in 1948 copied the Jeep concept including CV joints and front axles. Toyota Land Cruiser 1951 similarly adopted CV joint front-wheel drive learning from Allied Jeeps observed during post-war occupation of Japan. By the 1960s, four-wheel drive recreational vehicles, International Scout 1961, Ford Bronco 1966, Chevrolet Blazer 1969, all used CV joints, making 4WD mainstream.

The explosion of SUVs, sport utility vehicles in the 1980s, 1990s was enabled by CV joint technology pioneered for the Jeep. Every modern SUV, pickup truck with 4WD or all-wheel drive car uses CV joints. Billions manufactured annually, descendants of the Bendix Weiss design. While Bendix Weiss joints dominated World War II Jeep production, postwar automotive industry gravitated toward repsa type ball and cage joints for most applications.

The sixball reps design, though more expensive to manufacture initially, offered advantages as manufacturing technology improved. Higher articulation angles. Repza joints could operate at angles exceeding 45°. Bendix wise was limited to about 37°. Smoother operation. The ball cage maintained perfect geometry even with wear, while Bendix Wise could develop slight irregularities.

better suited for independent suspension. Postwar vehicles increasingly used independent front suspension, requiring joints with greater articulation. By the 1970s, virtually all automotive CV joints used Repza or similar ball and cage designs, but the Bendix Weiss concept survived in specialized applications requiring extreme durability over precision.

industrial equipment, mining vehicles, military applications. The fundamental principle using rolling balls to transmit torque through variable angles remains unchanged from 1940. Modern CV joints are descended directly from the wartime crash program that made the Jeep possible. Unlike famous wartime inventors, the Nordan bomb sites Carl Nordan, the proximity fuses Merurl tube, the engineers who adapted CV joint technology for mass production remain largely anonymous.

Bendix Aviation Corporation records don’t preserve detailed accounts of who designed the manufacturing processes for Bendix lace joints. Company histories mention CV joint production but focus on more glamorous products. Aircraft carburetors, brake systems, radio equipment. Similarly, Spicer manufacturing eventually ramped up CV joint production but never publicized the engineers who made it happen.

Corporate archives were scattered through mergers and acquisitions. Carl Probes, the designer who created the Banam prototype in 5 days, is somewhat known among Jeep enthusiasts. But the supply chain specialists who solved the CV joint shortage, remain forgotten. This reflects a broader historical pattern.

Dramatic innovations, the Jeep itself, are remembered while enabling technologies, the CV joints that made it work, fade from memory. Yet without CV joints, the Jeep would have been impossible. And without the jeep, American military logistics in World War II would have been fundamentally different and far less effective. In June 1940, when the US Army requested a lightweight four-wheel drive reconnaissance vehicle, American industry faced a technological gap.

No one manufactured constant velocity joints at scale. Europe had front-wheel drive cars using CV joints since the 1920s. But American automakers had ignored the technology. When war demanded it, industry had to learn fast, acquiring German designs, Zeppa, Bendix, Weiss, French designs, Tracta, and scaling production from hundreds to hundreds of thousands.

The challenge wasn’t invention. CV joints already existed. The challenge was manufacturing at wartime scale with wartime urgency. Bendix Corporation, more famous for brakes and carburetors, became primary supplier of CV joints for 360,000 Willies MB Jeeps. Ford using Zepa joints equipped 280,000 GPW Jeeps. Between them, they produced over a million CV joints in four years, more than the world had made in the previous two decades.

Those CV joints enabled the Jeep. The Jeep enabled mobile warfare, reconnaissance, communications, command, supply. Allied commanders from Eisenhower to Montgomery credited the Jeep as a critical factor in victory. Postwar, the CV joint quietly launched an entire vehicle category. Civilian Jeeps, Land Rovers, Land Cruisers, then Scouts, Broncos, Blazers, then SUVs, crossovers, all-wheel drive cars.

Today’s automotive landscape dominated by vehicles with driven front wheels descends directly from 1940s CV joint technology. Every time you see an SUV navigate a snowy intersection, remember that capability traces to a crash program in 1940 when American industry learned to manufacture ball and yolk joints that transmitted smooth power through variable angles.

The Jeep needed constant velocity joints. Industry delivered and quantities thattransformed not just military logistics but post-war transportation worldwide. Five steel balls precision ground and assembled in Toledo, Ohio, enabled the vehicle that won a war and launched an industry. That’s the power of seemingly minor mechanical components.

Solve one problem correctly and the applications multiply beyond imagination. America had no CV joints in 1940. By 1945, American factories had produced more CV joints than the rest of the world combined ever. The Bendix Weiss joint with its elegant fiveball geometry may have been superseded by more sophisticated designs, but its legacy indoors every time a four-wheel drive vehicle turns while accelerating, transmitting smooth power through rolling balls that automatically maintain constant velocity.

The joint that saved the Jeep became the joint that changed transportation forever.