The One-Eyed Director Who Renamed a Giant: Raoul Walsh’s Hidden Night on the Fox Lot That Turned Marion Morrison Into “John Wayne”—and Changed Hollywood Forever

On certain nights, Hollywood feels less like a place and more like a rumor.

The streets look ordinary, the studio gates stand tall and bored, and the air carries the faint perfume of eucalyptus, gasoline, and ambition. A security guard waves through a familiar car. A light flickers inside a soundstage. Somewhere, a typewriter refuses to stop.

And if you happen to arrive at just the right hour—when the sun has fully stepped away but the city hasn’t yet decided to sleep—you can almost believe the old stories: that careers were made in hallway shadows, that legends began with a glance, and that names could be rewritten like dialogue.

That’s how it felt on the Fox lot one evening in 1929, when Raoul Walsh walked as if he belonged to two different worlds at once.

He moved with the confidence of a man who’d already lived several lives. Not just experienced them—collected them.

Born in New York City, Walsh carried the city’s sharpness in his eyes and the rhythm of it in his stride. Yet there was something else layered underneath, like dust on polished boots: Texas, wide horizons, the echo of horses, and the kind of calm you only get when you’ve spent time around people who aren’t impressed by speeches.

He’d acted in the silent era, shared frames with early screen royalty, and directed pictures that helped teach audiences how to dream in motion. He wasn’t simply employed by Hollywood—he’d helped invent parts of it. His confidence wasn’t arrogance. It was the certainty of someone who had seen chaos up close and learned to keep walking anyway.

Walsh had an eye for the big picture.

Eventually, he would have only one of them.

People tell the story of his accident differently—because Hollywood never met a tale it didn’t want to re-stage. But the plain truth was this: an unpredictable mishap took his eye, and he refused to let it take his vision. He wore the patch without theatrics. Not as costume. As punctuation.

The patch made people look twice. Walsh made people listen.

That night on the lot, he wasn’t hunting for trouble. He wasn’t hunting for headlines. He was hunting for something rarer and more valuable: a face that could carry a horizon, and a presence that could stand still and still feel like a story.

A studio executive had tried to pull him into a meeting earlier, pressing schedules and budgets toward him like cards at a poker table. Walsh had waved it off.

“Tomorrow,” he’d said, already walking away.

“Raoul,” the executive called after him. “Where are you going?”

Walsh didn’t turn around. “Where the picture is.”

Fox was a machine back then: a city inside a city. There were carpenters and seamstresses, prop men, electricians, writers with ink-stained fingers, assistants juggling paper stacks like circus plates. There were actors rehearsing lines on benches, extras practicing the art of looking busy, and directors arguing with the sun because the sun never hit a mark.

Walsh walked through it all with the air of a man listening to a private radio station—one tuned to instincts rather than announcements.

Near a back corridor, where noise thinned into pockets of quiet, he noticed a figure moving crates.

A big figure.

No—big was too small a word.

The young man was tall, broad-shouldered, and built like the kind of athlete who could make crowds gasp without saying a word. His sleeves were rolled up. His hair was rumpled. He moved with the efficient stubbornness of someone who didn’t expect the world to hand him anything.

Walsh paused, not dramatically. Just enough to become still.

The young man set down a crate, wiped his hands on his trousers, and straightened. When he turned, his face caught a shard of light from an overhead lamp.

It wasn’t a “perfect” face in the magazine sense. It wasn’t delicate. It wasn’t polished.

It was honest.

A jawline like a promise. Eyes that looked as if they’d learned patience by necessity. A mouth that could be tough or kind depending on the day.

Walsh watched him for a moment longer than politeness required.

The young man noticed.

He didn’t flinch. He didn’t rush to impress. He simply met Walsh’s gaze with a calm that suggested he was used to being measured.

Walsh stepped closer. “What’s your name?”

The young man hesitated, as if unsure whether this was a trick.

“Marion Morrison,” he said.

Walsh repeated it quietly, tasting the syllables. “Marion Morrison.”

A name like a door that opened to the wrong room.

The young man added quickly, “People call me Duke.”

Walsh’s mouth twitched. “Why Duke?”

The young man shrugged. “Old nickname.”

Walsh nodded as if filing that away. Then he asked the question that mattered more than the name.

“Ever acted?”

“A little,” Morrison said. “Nothing important.”

Walsh’s stare didn’t waver. “Do you want to?”

Morrison’s expression changed—not into eagerness, not into desperation, but into something sharper: alertness. Like a man hearing a distant train and deciding whether to run for it.

“I wouldn’t say no,” he said carefully.

Walsh looked him up and down again—height, shoulders, stance. The shape of him suggested a screen that could hold distance: a Western horizon, a long trail, a man alone against a wide world.

Walsh leaned in slightly. His voice was low, like a secret you had to earn.

“If you’re going to be on film,” Walsh said, “you need a name that sounds like it belongs on the side of a mountain.”

Morrison blinked. “I—sir?”

Walsh smiled, a small, certain smile. “Come with me.”

They walked. And as they walked, the Fox lot changed around them—corridors turning into possibilities, shadows turning into stages. Crew members glanced up and did double takes, partly because of Walsh and partly because of the tall young man trailing him like a question mark.

Walsh didn’t explain. He rarely did. He didn’t sell people on his ideas. He behaved as if the idea had already happened and everyone else was simply catching up.

They entered a small office where walls were covered with pinned stills and scribbled notes. A few men were sitting around a table, arguing about travel logistics and camera rigs. Walsh waved a hand.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “we’re done arguing.”

One of the men looked annoyed. “Raoul, we’re not done—”

Walsh pointed at Morrison. “This is what we needed.”

Silence dropped like a curtain.

Morrison shifted, suddenly aware of his hands, his posture, his boots. He looked too big for the room, like a horse in a parlor.

A producer frowned. “Who’s this?”

“A lead,” Walsh said.

Another man laughed in disbelief. “A lead? He’s a—”

“A what?” Walsh cut in. His tone wasn’t angry. It was colder than anger: certainty.

The room studied Morrison like a new tool.

Walsh turned to Morrison. “Stand there.”

Morrison did.

Walsh moved a desk lamp, angled it, and watched how the light traveled across Morrison’s face. It was almost surgical—Walsh adjusting brightness and shadow the way other men adjusted ties.

“Look over there,” Walsh said.

Morrison looked.

“Now look back,” Walsh said.

Morrison looked back.

The difference wasn’t in the movement. It was in the presence. Morrison didn’t perform a gesture. He occupied space. His stillness had weight.

Walsh exhaled, like someone hearing a chord land perfectly.

“All right,” Walsh said. “We’re going to test him.”

One of the men protested. “Raoul, we don’t have time to test—”

Walsh lifted a finger. “Then we don’t have time to waste.”

Later, under the controlled chaos of a test shoot, Morrison stood in front of a camera that looked like a mechanical animal. A technician adjusted focus. Someone clapped a slate. The sound echoed like a gavel.

Walsh watched through a viewfinder with the intensity of a man trying to see ten years into the future.

“Don’t act,” Walsh told Morrison. “Just be there. Like you belong there.”

Morrison swallowed. “I do.”

Walsh’s smile flashed. “Good answer.”

The camera rolled.

Morrison took a few steps forward, as instructed, then stopped. He looked toward an imagined horizon—somewhere beyond the lights, beyond the studio walls, beyond the doubt in other men’s eyes.

Walsh saw it immediately: the way the lens liked Morrison, the way the frame held him as if it had been waiting. Morrison didn’t need fancy expressions. He had something simpler, rarer: credibility.

Walsh walked toward him after the take. “You know what’s strange?” he said.

“What?” Morrison asked.

Walsh gestured at the camera. “That machine loves you.”

Morrison didn’t know what to say. So he told the truth.

“I don’t know anything about machines,” he said. “I just want to work.”

Walsh nodded. “You will.”

That night, Walsh didn’t go home right away. He stayed in his office while the lot emptied, while the noise drained away, while Hollywood became quieter and more dangerous—because in quiet you can hear your doubts.

He stared at a notepad. He wrote names, crossed them out, wrote more.

Marion Morrison didn’t fit the shape of the story Walsh wanted to tell—not because Morrison lacked something, but because the name didn’t match the silhouette.

Walsh knew that names were spells. They could make people lean in. They could make people believe before a man even spoke.

He thought of rivers and deserts. He thought of a man walking into a town with dust on his boots and history behind his eyes.

He thought of something strong, simple, unforgettable.

Then he wrote two words:

John Wayne

He stared at it.

It stared back.

It had the sound of a bell. The shape of a legend.

Walsh leaned back, satisfied the way a sculptor is satisfied when the face finally emerges from stone.

The next day, he handed Morrison the paper.

Morrison read it slowly. “John Wayne.”

Walsh watched his reaction. “Do you hate it?”

Morrison looked up. “I don’t know what I feel.”

Walsh nodded. “Good. It means it’s bigger than your comfort. That’s what you need.”

Morrison hesitated. “Why ‘John’?”

Walsh shrugged. “Because it sounds like a man you can trust.”

“And ‘Wayne’?”

Walsh’s one visible eye sharpened. “Because it sounds like a man you wouldn’t want to underestimate.”

Morrison looked at the paper again, as if it might change if he blinked. Then he did something that would define him as much as any film role: he accepted the weight.

“All right,” he said quietly. “If you say so.”

Walsh smiled. “I do.”

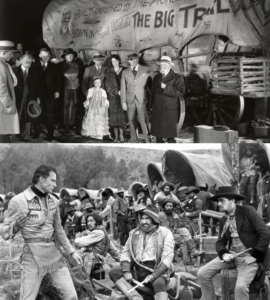

In 1930, when The Big Trail began its long, grueling production, Hollywood was still teaching itself how to be modern. Westerns weren’t nostalgia yet; they were mythology in the making. The landscape mattered. Distance mattered. The sense of a man against the world mattered.

Walsh wanted scale. He wanted vastness. He wanted the audience to feel as if the screen had opened into another life.

To get that, he pushed hard—not cruelly, not carelessly, but relentlessly. He demanded authenticity of the environment: long trails, sweeping spaces, human beings dwarfed by nature. It wasn’t simply about spectacle. It was about meaning.

John Wayne—still learning the rhythm of the camera, still learning how to carry silence—had to become more than a tall man in a costume. He had to become a symbol without pretending to be one.

One morning, during a break, Wayne found Walsh alone, staring out at the landscape like it was a puzzle.

Wayne cleared his throat. “Mr. Walsh.”

Walsh didn’t turn. “Yes?”

Wayne hesitated. “Why me?”

Walsh finally looked at him. “Because you look like tomorrow.”

Wayne frowned. “I’m just trying not to mess up.”

Walsh chuckled. “You will mess up. Everyone does. But you’ll learn. And one day they’ll forget your mistakes and remember your shape in the doorway.”

Wayne stared. “My shape?”

Walsh tapped his own chest lightly. “A story isn’t only words. It’s presence. You have it.”

Wayne looked down, almost embarrassed. “I don’t feel like I do.”

Walsh’s gaze softened, and for a moment the hard-edged director looked like a teacher.

“That’s because you’re honest,” Walsh said. “A dishonest man thinks he’s great before he earns it. An honest man doubts. Doubt can be useful, if you don’t let it steer.”

Wayne nodded slowly. “So what do I do?”

Walsh turned back toward the horizon. “You keep walking.”

Later in his life, people would talk about Walsh like he was made of pure legend: the New York boy who rode with cowboys in Texas, the director who had survived the silent era and helped shape the sound era, the man who could guide actors like chess pieces and still make them feel alive.

They would talk about his films—The Thief of Bagdad, with its dreamlike sweep; Sadie Thompson, with its intensity; the rugged confidence he brought to stories that needed speed and grit.

But the secret to Walsh was never only in his resume.

The secret was that he knew how to see people.

He could spot the line between performance and truth. He could recognize when a face contained a future. He could sense when an actor wasn’t simply acting but becoming the kind of figure audiences would carry in their minds for decades.

And he did it all while carrying his own kind of damage with quiet defiance.

If the accident that took his eye taught him anything, it was that life doesn’t ask permission before it changes your body, your plans, your sense of self.

Walsh responded the only way a true filmmaker could: he adapted. He reframed. He kept directing.

There’s a certain kind of bravery in that—a bravery that doesn’t announce itself.

Years later, when John Wayne had become John Wayne in the way the public understands it—big, iconic, undeniable—someone asked Walsh if he knew what he’d done that first night on the Fox lot.

Walsh’s answer, according to the people who loved telling stories about him, was simple.

“I didn’t make him,” Walsh supposedly said. “I just gave him the right door.”

Whether he said it exactly that way doesn’t matter.

Because the truth is visible in the outcome.

A tall young man named Marion Morrison walked onto a lot thinking he might get another small job, another day of labor, another step toward something he couldn’t quite name.

A director with a patch and a restless mind looked at him and saw a myth waiting to be lit.

And somewhere between a corridor and a camera test, between a plain name and a legendary one, Hollywood shifted—quietly, dramatically, forever.

That’s why, on days like this, people still talk about Raoul Walsh.

Not only because he directed classics.

Not only because he lived like a story.

But because he understood the most mysterious power in cinema:

Sometimes the most shocking twist isn’t a plot twist at all.

Sometimes it’s a single moment when someone sees you—truly sees you—before the rest of the world catches up.

And that kind of moment doesn’t just change a career.

It changes history.