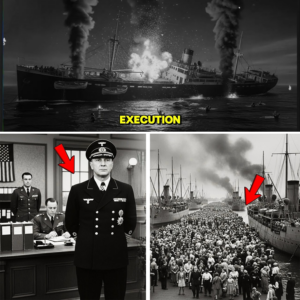

The Grand Admiral on Trial: Why America Didn’t Hang Him After the War—And How a Desperate Sea Evacuation Saved Nearly Two Million Souls

The first time Lieutenant Andrew Keller saw the Grand Admiral, he expected a monster.

Not because the man in front of him had fangs or theatrics, but because everyone—newspapers, soldiers, grieving families—seemed to need him to look like a villain. A villain made the war feel tidy. A villain made the math of loss feel explainable.

Instead, the man behind the glass looked like a strict schoolmaster who’d been forced to sit through his own lecture. His posture was stiff. His hair, once famous under a cap with gold trim, was now plain and combed back. His expression said nothing and everything at once: defiance, fatigue, calculation, and the hardest thing to stomach—

certainty.

Keller stood in the corridor outside the interview room, holding a folder stamped with the seal of the tribunal. The hallway smelled of cigarette smoke, wet wool, and ink. Nuremberg in winter had a way of turning every building into a chimney and every conversation into a confession.

“Don’t stare,” Major Evelyn Hart said beside him.

Keller blinked. “I wasn’t.”

“You were,” Hart replied, and her tone made it sound like a correction, not an insult. She’d been a Navy lawyer before the war ended, and she spoke the way a scalpel looked—precise, gleaming, and uninterested in excuses.

Keller shifted the folder in his hands. “It’s just… I thought he’d look different.”

Hart’s eyes stayed on the glass. “That’s the trap. If evil looks like evil, we can stop searching for it in ordinary faces.”

Keller swallowed. “So what are we looking for?”

Hart finally glanced at him. “Truth that can survive a courtroom.”

She tapped the folder. “And this man, Keller, is made of contradictions.”

Inside the folder were two stories that fought each other like rival claimants to the same throne.

One story said: Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz—the submarine commander who presided over ruthless sea war, who inherited the collapsing Reich for its final days, who signed orders and served a regime that burned the world.

The other story said: the same man orchestrated the largest sea evacuation in history, a frantic operation across the Baltic that pulled civilians and soldiers out of a closing trap—nearly two million people fleeing winter, chaos, and the front line’s collapse.

Two million.

It was a number so large it sounded like propaganda. The kind of number that made you suspicious.

Yet the reports kept repeating it, from captured German records to Allied naval intelligence summaries.

And now, the question was no longer whether Dönitz had served the wrong cause.

The question was whether, in the eyes of the tribunal, that cause would define him completely—or whether a single operation could bend the rope that waited for men like him.

Hart opened the door. “Come on. Let’s meet the contradiction.”

The interview room was smaller than Keller expected. Not a dungeon. Not a dramatic chamber. Just a table, two chairs, a guard, and a window that stared at grey sky like an accusation.

Dönitz sat already, hands folded. He didn’t rise. He didn’t offer a greeting. He watched Hart and Keller sit as if they were students arriving late.

Hart laid the folder on the table and opened it to a marked page.

“Grand Admiral Dönitz,” she said, “we’re going to talk about the Baltic evacuation.”

Dönitz’s eyes moved to the page, then back to Hart. “You call it an evacuation,” he said evenly. “We called it a withdrawal.”

Hart’s expression didn’t change. “You can call it whatever you like. The question is whether you directed it.”

“I did.”

Keller felt the bluntness of that answer. No hedging. No theatrics. Just a statement dropped like a weight.

Hart leaned forward. “Nearly two million civilians and troops were moved by sea in a matter of months. In winter. Under attack. With ports overcrowded and ships scarce.”

Dönitz’s mouth tightened. “Desperation creates efficiency.”

Keller couldn’t stop himself. “Or chaos.”

Dönitz turned his gaze to Keller for the first time. The eyes were not wild. They were cold-blue and disciplined.

“Lieutenant,” Dönitz said, “when the world collapses, chaos is the default. If you want survival, you impose order.”

Hart raised a hand slightly—Keller’s warning to stay quiet. Then she said, “Order under a regime that was already guilty.”

Dönitz’s jaw flexed. “Guilt is a word for the court. I’m a sailor. I dealt with facts: the front was broken, civilians were trapped, and winter was coming.”

Keller felt something unpleasant in his chest: the possibility that a man could speak truth in one sentence and be unforgivable in the next.

Hart flipped to another page. “We also need to discuss the submarine war.”

A flicker—small, but real—crossed Dönitz’s face. Annoyance, perhaps. Or recognition that the conversation had moved from the only part of his legacy that looked like rescue.

“The accusations are familiar,” Dönitz said.

Hart’s voice sharpened. “Because they’re serious.”

Dönitz’s gaze stayed steady. “And because many navies did similar things when they believed they had to.”

Keller understood the implication before Hart said it aloud.

Comparisons were weapons in court.

And Dönitz had brought one to the table.

That evening, Keller walked through the tribunal offices with the folder pressed under his arm like a shield.

Nuremberg at night felt unreal—ruins, patched streets, and a courthouse lit like a stage. Soldiers passed in the corridor carrying coffee, documents, and the quiet of men who had seen too much and were trying to put it into categories.

Keller found Hart at a desk piled with affidavits.

She didn’t look up. “You’re thinking.”

Keller hesitated. “Is it possible he saved those people for the right reason?”

Hart’s pen paused. “What right reason?”

“To keep them alive,” Keller said quickly. “To prevent—” He searched for words that wouldn’t turn the room into a sermon. “To prevent more suffering.”

Hart finally looked up. “Keller, you’re asking if one action can redeem a career.”

“I’m asking if the court will see it that way.”

Hart leaned back, eyes tired. “The court isn’t a church. It doesn’t deal in redemption. It deals in responsibility.”

Keller nodded, but it didn’t quiet the tug inside him. Two million lives—mothers, children, old men, wounded soldiers, terrified teenagers—were not a small thing.

“Then why does it matter?” he asked.

Hart’s expression hardened. “Because the defense will make it matter. They’ll say, ‘How can you hang a man who saved so many?’ And the public will hear that and start choosing sides. That’s how history gets hijacked: by numbers that are too big to visualize.”

Keller swallowed. “So what’s our answer?”

Hart tapped the pile of papers. “Our answer is to separate the rescue from the regime. To show he could order ships to save people and still serve a machine that did enormous harm.”

Keller whispered, almost to himself, “But if we separate everything… what’s left of a person?”

Hart’s eyes softened for the briefest moment. “A person is exactly what the law tries to pin down. And it’s harder than people think.”

The next day, Keller was assigned to sift naval records: convoy logs, radio transcripts, ship manifests, and the kind of documents that made tragedy look like bookkeeping.

He learned names that sounded like geography quizzes—Gotenhafen, Pillau, Königsberg—and the constant rhythm of movement: ships out, ships back, ships sunk, ships overloaded, ships delayed.

The evacuation had a pulse. A brutal one.

As Keller read, he began to see the operation as a giant hand pulling people across icy water while another hand—war itself—kept trying to pry fingers loose.

There were moments of astonishing coordination: convoys assembled under threat, crews improvising, civilian ferries pressed into service. There were also moments of horrifying indifference: overcrowding, poor planning, and the cold arithmetic of choosing who got onto which deck.

But the sheer scale remained undeniable.

Nearly two million.

That number kept standing up again, no matter how many pages Keller turned.

Late afternoon, Hart arrived with a new document and slid it across Keller’s desk.

“What’s this?” Keller asked.

Hart didn’t smile. “A headache.”

Keller read the heading: an affidavit from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

Keller’s eyes widened. “Nimitz?”

Hart nodded. “The defense wanted it. The tribunal allowed it.”

Keller skimmed quickly, heart sinking as he recognized the shape of the argument: that unrestricted submarine warfare—one of the charges against Dönitz—had also been conducted by the U.S. Navy in the Pacific.

It wasn’t an excuse.

It was a mirror.

Keller looked up. “This changes everything.”

Hart’s gaze was flat. “It changes the courtroom math. Not the moral math.”

“But if the court admits that—”

“If the court admits that major navies used similar tactics,” Hart said, “it becomes harder to justify the ultimate penalty on that charge. Which means the prosecution must lean heavier on other responsibilities.”

Keller stared at the paper. “So the evacuation plus this affidavit—”

“—means the defense will build a narrative,” Hart finished. “Not just ‘he saved lives,’ but ‘he fought a naval war the way everyone did.’”

Keller felt anger rise—not at Nimitz, exactly, but at the reality that war blurred lines until even a courtroom struggled to draw them cleanly.

Hart stood over him. “This is why we don’t chase monsters, Keller. We chase proof.”

On the day of testimony about the Baltic operation, the courtroom filled as if people expected a ship to sail through the doors.

Reporters came hungry. The public gallery was tense. Even the guards seemed more alert, as if the words themselves might trigger riots outside.

Dönitz took the stand.

He spoke with a sailor’s economy: routes, tonnage, timing, decisions under pressure. He described the operation as if it were a storm—something you managed, not something you celebrated.

Then the defense asked the question that Keller knew was coming.

“Grand Admiral,” the attorney said, “how many people were evacuated by sea under your direction?”

Dönitz’s face didn’t change. “Approximately two million.”

A murmur moved through the room like wind.

The attorney’s voice warmed, turning the number into a moral trophy. “And would you agree that those lives would have been lost otherwise?”

Dönitz paused. The smallest hesitation—like a man deciding how much humility to pretend.

“I believe many would not have survived,” he said.

The defense turned toward the judges like a man presenting a prize. “Then we are not looking at a man who sought only destruction. We are looking at a man who, in the final months, used the sea to save human life on a massive scale.”

Keller’s stomach tightened. The argument was sharp because it used something true.

Then Hart rose for cross-examination, and the temperature of the room changed.

“Grand Admiral,” Hart said, voice calm, “you speak of saving lives. Do you claim you opposed the regime you served?”

Dönitz’s eyes narrowed. “No.”

Hart nodded, as if confirming a point on a map. “Do you claim you were unaware of its nature?”

Dönitz’s jaw flexed. “I was a military leader.”

Hart’s tone sharpened. “That’s not an answer. Were you unaware?”

Dönitz held her gaze. “I knew we were at war.”

Hart leaned in slightly. “War is not a blank check for everything a regime does. Were you unaware?”

A long pause.

Then Dönitz said, controlled, “I knew the regime was harsh.”

Harsh.

Keller felt the understatement hit the room like insult.

Hart didn’t flinch. “And yet you continued to serve.”

Dönitz’s voice remained even. “I served Germany.”

Hart’s eyes were steel. “You served a government. Governments can be judged.”

Dönitz’s mouth tightened. “So can victors.”

A stir—sharp, dangerous—ran through the gallery. The defense attorney looked satisfied. It was bait: the “victor’s justice” argument, thrown like a spark into dry grass.

Hart didn’t take it.

Instead, she turned the blade back to the evacuation itself.

“Grand Admiral,” she said, “was the evacuation conducted only for humanitarian reasons?”

Dönitz’s expression flickered—annoyance, perhaps.

Hart continued. “Or was it also conducted to preserve military manpower? To protect combat forces? To prolong resistance?”

Dönitz’s eyes stayed on Hart. “It was conducted to remove those in danger.”

Hart’s voice stayed steady. “That’s not what I asked.”

Dönitz exhaled through his nose. “Yes,” he said finally. “It included soldiers. Of course it did. The war still existed.”

Hart nodded once. “So the evacuation served dual purposes: saving civilians and preserving military strength.”

Dönitz didn’t answer.

Hart’s eyes hardened. “And you, Grand Admiral, were the man deciding which ships sailed, which ports were prioritized, and how long that resistance could continue.”

Silence.

Hart’s final question landed softly but with weight.

“Do you understand why the world is asking whether you are a rescuer—or merely a commander moving pieces until the last possible day?”

Dönitz looked forward, jaw set. “The world may ask what it likes.”

Hart said quietly, “So will this court.”

That night, Keller found Hart alone in the hallway, staring at a window that reflected the courthouse lights like distant flares.

“You did well,” Keller offered.

Hart’s reply was immediate. “Did I?”

Keller hesitated. “You didn’t let him own the narrative.”

Hart’s gaze stayed fixed on the glass. “Narratives are stubborn. People don’t want complexity. They want a simple decision: hang him or praise him.”

Keller’s voice lowered. “What do you want?”

Hart finally looked at him. Her eyes were tired—tired in a way that had nothing to do with sleep.

“I want accountability,” she said. “Not theater. Not revenge. Accountability that teaches the next generation what happens when leaders hide behind ‘I served’ like it’s armor.”

Keller swallowed. “But if the court doesn’t hang him—”

“Then the public will scream,” Hart said. “And some will scream for the wrong reasons.”

Keller’s mind returned to the number again. Two million. A sea of faces he couldn’t picture.

He asked the question that had been eating him since the first interview.

“Is it possible,” Keller said, “that he did something good at the end because he finally saw the cliff?”

Hart’s expression didn’t soften.

“It’s possible,” she said. “And it’s also possible he did it because losing civilians makes you lose the future you’re trying to preserve.”

Keller frowned. “Those aren’t the same.”

Hart nodded. “No. They aren’t.”

Then she added, “But in court, motives are hard to prove. Actions are easier.”

Keller stared at the reflected lights. “So the court will judge the action.”

Hart’s voice was quiet. “And the action will save him from one punishment while not erasing what he chose to be.”

The verdict arrived like winter sunrise: slow, pale, inevitable.

Keller sat in the courtroom as the judgment was read. He watched faces—reporters ready to sprint, soldiers stiff with restraint, civilians trying to interpret history in real time.

When the sentence for Dönitz was announced—imprisonment rather than death—Keller heard the collective exhale in the room. Some sounded relieved. Others sounded furious. A few sounded confused, as if the world had refused to fit into their preferred shape.

Outside, the arguments began immediately.

Headlines pushed one angle or another: mercy, hypocrisy, politics, “victor’s justice,” “saved lives,” “war leader,” “too lenient,” “too harsh.”

It became a public brawl over the meaning of justice itself.

And somewhere in that noise, the Baltic evacuation became a strange kind of currency. People spent it to buy whatever conclusion they wanted.

Keller walked back through the tribunal corridors, the folder under his arm feeling heavier than ever. He found Hart at her desk, eyes on paperwork as if the courtroom hadn’t just tried to rearrange morality.

“It’s done,” Keller said.

Hart didn’t look up. “Nothing is ever done. It just becomes history.”

Keller hesitated. “Do you think we failed?”

Hart’s pen stopped. She looked up, and for the first time since Keller had met her, her expression showed something like sadness.

“No,” she said. “We did what courts can do. We proved some things. We punished some things. We drew some lines.”

Keller’s voice caught. “But the people he evacuated—”

Hart nodded once, acknowledging the truth without surrendering to it. “Those people mattered. Their lives mattered. And it matters that they lived.”

Keller leaned forward. “Then why does it feel wrong?”

Hart’s eyes held his. “Because justice isn’t a feeling. It’s a structure. And structures have limits.”

She stood and walked around the desk, stopping beside Keller.

“You want a clean ending,” she said softly. “Everyone does. But the war didn’t give clean endings. It gave aftermath.”

Keller whispered, “So what do we do with the contradiction?”

Hart’s answer was quiet and sharp.

“We tell it honestly,” she said. “We don’t let the evacuation turn him into a saint. And we don’t let his service to a brutal regime erase the fact that two million people got another chance at life.”

Keller looked down at the folder. The pages seemed less like documents now and more like a storm captured in ink.

Hart added, “And we remember that sometimes, history doesn’t spare a man because he deserves sparing. It spares him because the world is trying to teach itself a lesson without tearing itself apart.”

Keller breathed out slowly. “What lesson?”

Hart’s gaze drifted toward the window where the sky was beginning to brighten.

“That leadership can do catastrophic harm,” she said, “and still do one thing that saves lives. Which means we can’t outsource morality to outcomes. We have to judge choices.”

Keller stared at the morning light. “And the public?”

Hart’s mouth tightened. “The public will argue forever.”

She picked up a new file, already moving on because the work didn’t pause for philosophy.

Then, almost as an afterthought, she said, “But here’s the part I don’t want you to forget, Keller.”

Keller waited.

Hart’s voice dropped. “Two million lives saved doesn’t erase what came before. And what came before doesn’t make those saved lives meaningless.”

Keller nodded, feeling the uncomfortable truth settle into him like cold metal warming slowly in a hand.

Outside, Nuremberg’s streets remained broken and patched and busy. People were rebuilding. People were grieving. People were writing their own private verdicts in kitchens and bars.

And somewhere, in a prison cell, a Grand Admiral lived on—neither fully condemned by the public nor fully redeemed by the sea.

A contradiction the world would keep arguing about, because it was easier to fight over a man than to face the real terror:

That history sometimes spares people not because they are simple…

…but because they are complicated.

THE END