Rommel Whispered a Chilling Prediction About Patton—Then His Own Commanders Brushed It Off, and the Next 72 Hours Turned Their Maps Into Nightmares No One Dared Describe

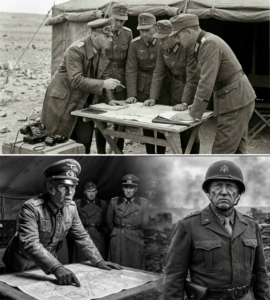

In the dim hours before dawn, when the desert seemed to hold its breath and even the wind moved cautiously, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel stood alone over a spread of maps. The paper was worn thin at the folds, corners softened by weeks of handling, but his eyes were sharp, restless. He traced invisible lines with a gloved finger, not marking where forces were, but where they would be. To those who knew him well, this was when Rommel was most dangerous—not in the roar of engines or the glare of midday sun, but in silence, listening to instincts shaped by years of close calls and narrow escapes.

That morning, his thoughts circled one name again and again: George S. Patton.

Rommel had studied many opponents, but Patton unsettled him in a way he found difficult to explain. This was not fear in the ordinary sense. It was a recognition, the same kind one chess player feels when another across the board sees two moves further into the future. Patton was unpredictable, bold to the point of recklessness, yet guided by a strange internal logic that often placed him exactly where his enemies least expected. Rommel believed that underestimating such a man was not merely a mistake—it was an invitation to disaster.

When his senior commanders gathered later that morning, the mood was routine. Reports were read, supply figures discussed, positions reviewed. Then Rommel spoke, his voice calm but edged with urgency. He warned them that Patton would not behave as their projections suggested. He would not advance cautiously, nor pause when logic said he should. He would strike at odd hours, from unlikely directions, and with a speed designed to confuse rather than overwhelm.

Some of the generals exchanged glances. Others smiled thinly. One of them, a veteran of countless briefings, gently suggested that Rommel was giving Patton too much credit. After all, intelligence estimates showed the opposing forces stretched thin, focused elsewhere. Another added that morale on the other side had been inconsistent at best. Patton, they believed, was all noise and theatrics.

Rommel listened, his expression unreadable. When the room quieted, he repeated his warning, more softly this time. “He will move when you think he cannot,” he said. “And when you realize what he has done, it will already be too late to stop it.”

The meeting ended without any changes to the plan.

As the day wore on, Rommel’s unease grew. He paced his quarters, rereading reports that told him nothing new and yet seemed full of hidden meaning. Every delay in communication, every ambiguous message from the field, felt like a thread being pulled loose. He remembered stories of Patton driving his units relentlessly, of sudden appearances that shattered expectations. Rommel suspected that even now, Patton was studying him in return, searching for habits, rhythms, and weaknesses.

Night fell quickly in the desert. Stars emerged in cold abundance, and with them came a deceptive calm. Outposts reported nothing unusual. Radios crackled with routine updates. To anyone else, it would have seemed that the day had proven Rommel wrong. Yet he could not sleep. He sat at his desk, writing notes he might never send, detailing possibilities that others would dismiss as imagination.

Just before midnight, the first sign arrived—not in the form of an attack, but a question. A junior officer called in to report movement far to the south, faint and irregular. It was dismissed by headquarters as local activity, perhaps reconnaissance, perhaps nothing at all. Rommel said nothing, but inside, his certainty hardened. This was exactly how Patton worked: testing reactions, watching responses, measuring hesitation.

By the next afternoon, the reports multiplied. Supply routes were disrupted in places considered safe. Units reported encountering resistance where none was expected, then finding it gone just as suddenly. Confusion spread, not because of overwhelming force, but because no one could agree on what was actually happening. Orders were revised, then revised again. The maps began to look messy, cluttered with arrows that contradicted each other.

Rommel called for another briefing. He pointed out the pattern forming beneath the chaos. “This is not random,” he insisted. “This is deliberate misdirection.” But again, his words met resistance. Some believed the enemy was improvising out of desperation. Others argued that reacting too strongly would expose their own positions. The idea that Patton had orchestrated the confusion from the start seemed far-fetched to them.

Late that evening, a message arrived confirming what Rommel had feared. A major concentration of opposing forces had appeared far from where they were expected, cutting across assumptions that had shaped weeks of planning. The realization hit like a cold wave. The move was daring, even audacious—and unmistakably Patton’s style.

For Rommel, there was no satisfaction in being proven right. Only frustration, and a deep sense of inevitability. He worked through the night, issuing instructions, trying to contain the damage. But every response felt one step behind. The speed of events outpaced the machinery of command. Units that should have linked up missed each other by hours. Opportunities closed before they could be seized.

As dawn broke on the third day, the situation had shifted dramatically. Positions once considered secure were now questionable. Lines of communication strained under the weight of conflicting demands. The enemy seemed everywhere and nowhere at once. Patton’s presence was felt less through direct confrontation and more through the constant pressure of uncertainty. He forced decisions, and punished hesitation.

Rommel stood once more over his maps, now marked and re-marked until they bore little resemblance to their original clarity. He thought back to his warning, to the moment when he might have pushed harder, argued longer, insisted more forcefully. Yet he also knew that conviction could not always overcome disbelief. His generals had relied on formulas that had served them before. Patton had simply refused to follow them.

Stories later told of those days would focus on movements and outcomes, on territory gained or lost. Few would speak of the quieter struggle—the battle of perception and expectation that unfolded before the first decisive engagement. Rommel understood that this was where Patton truly excelled. He did not just defeat positions; he unsettled minds.

In the weeks that followed, as the campaign continued to evolve, Rommel’s respect for his adversary deepened. He spoke less often of Patton, but when he did, his tone carried a gravity that others now recognized. The earlier smiles were gone. The dismissals replaced by cautious silence. The name Patton no longer sounded theatrical. It sounded real.

Years later, long after the dust had settled, some of those who had been in that first meeting would remember Rommel’s words. They would recall the calm certainty with which he had described a danger they chose not to see. And in quieter moments, they would wonder how different things might have been if they had listened—not to fear, but to experience.

Rommel never claimed to have predicted the future. He only believed that patterns, once recognized, demanded respect. His warning about Patton was not a prophecy, but a plea to abandon comfort and embrace uncertainty. That it was ignored became, in its own way, a lesson as enduring as any victory or defeat.

And somewhere in that vast, silent desert, the echo of those unheeded words seemed to linger—a reminder that the most unsettling threats are often announced softly, long before they arrive.