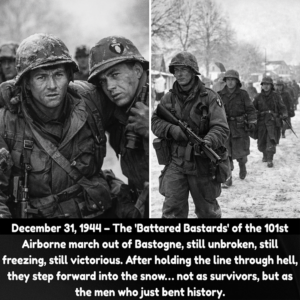

New Year’s Eve 1944: The ‘Nuts!’ Note Wasn’t the Real Shock—What the 101st Found as They Stepped Out of Bastogne at Dawn Still Gives Veterans Chills

They told us the town was just a dot on a map—seven roads crossing in a place most of us couldn’t pronounce correctly. Bastogne. A name that sounded like a cough at first, until it became a vow.

By New Year’s Eve, 1944, I had said it so many times it felt like a password.

Bastogne.

We’d arrived days earlier in a rush of trucks, cold air, and half-answered questions. Then the roads tightened, the sky lowered, and the circle around the town closed like a slow fist. The weather pinned everything down—planes, hopes, even the horizon. People talk about the siege like it was one long moment, but inside it you measured time in smaller units: a canteen cap of coffee, a strip of bandage, the crackle of a radio that still worked when it felt like nothing else did.

I was a radio operator in the 101st Airborne—one of the “Screaming Eagles,” though most of the time we weren’t screaming. We were listening. Listening for orders. Listening for the next sound that meant the world was changing again.

My hands were always either numb or shaking. Sometimes both. You learn strange things in winter: how to warm your fingers by pressing them against the back of your neck, how to keep a battery alive by sleeping with it under your coat, how to smile with only half your face because the other half has forgotten how.

On the evening of December 22, the word slipped through the town faster than any jeep could drive: the German forces had sent a surrender demand.

It arrived like a visitor you didn’t invite, delivered formally, with polished language and a hard edge underneath. The message promised the “honorable” option and hinted at what the alternative might be.

I wasn’t in the room when General McAuliffe read it, but the story traveled with a speed that didn’t require witnesses. Someone said he stared at the paper, blinked once, and barked a single word—like a man swatting away a fly that had mistaken him for dinner.

“Nuts.”

That was it. One word. Not a speech. Not a performance.

Just a refusal sharp enough to cut through fear.

Later, when people asked what it meant, the explanation got cleaned up and repeated until it became part of the legend, but the core stayed the same: a plain answer to an impossible demand.

Even if you’d never met McAuliffe, that one word belonged to all of us after that.

It did something strange to the air.

It made you stand a little straighter, even if your knees ached and your stomach argued with your pride. It made you remember you were not just cold men in a surrounded town—you were a line someone else needed.

And we held.

We held through the days when the sky stayed shut and the roads stayed dangerous and the supplies felt like a rumor. We held through the nights when the wind sounded like it was trying to pull the town apart board by board. We held while the world beyond Bastogne fought to reach us.

Then, on December 26, everything changed in a way you could hear.

First, the sky opened.

Not like a gentle curtain—like a locked door kicked wide. The clouds split and the light came down pale and sudden. Above us, aircraft appeared—dark shapes against bright winter—dropping bundles that floated like slow blessings. Men who hadn’t cheered in days started cheering like it was the first language they’d ever learned. Warfare History Network+1

And on the ground, word arrived that a corridor had been opened to Bastogne—Patton’s forces pushing up from the south, breaking the tightest part of the ring. No one pretended the danger vanished instantly, but the feeling was unmistakable: the town could breathe again. Wikipedia+1

After that, time started moving differently.

It didn’t become easy. It just became possible.

By December 31—New Year’s Eve—Bastogne was no longer a sealed pocket, but it was still a hard place to stand. The wider battle continued, and the front remained tense into early January. Wikipedia+1

That night, I remember the color of the sky most.

It wasn’t fully dark yet, but it wasn’t daylight either. It was the shade of a bruise—deep blue with gray underneath. Snow sat in the corners of broken walls like it was trying to make the rubble look polite.

We were staged near an intersection that had once been ordinary—just a place where a bakery might’ve been and a kid might’ve ridden a bicycle. Now it was a landmark made of caution.

I was crouched behind a half-wall with my radio set tucked close, because the cold had made the thing temperamental. My buddy, Lenny, sat beside me, rubbing his hands and muttering threats at the weather.

“You ever notice,” he said, “how winter acts like it’s doing you a favor?”

I smiled without showing teeth. “Winter’s got a sense of humor.”

“It’s got a grudge,” he corrected.

Somewhere behind us, an engine coughed into life and went quiet again. Somewhere to our left, a distant thump rolled across the fields—far enough that it wasn’t immediate, close enough that it still mattered. The sounds of the front weren’t constant explosions like in the movies; they were punctuation. You learned to hear which noises were commas, which were question marks, and which were periods.

A runner came by with a folded note and tapped my shoulder.

“Radio,” he said. “They want you at command.”

I slung the set and followed, boots crunching over snow that had been walked into ice. We moved past a group of medics bent over their work, faces calm in a way that made you believe calm could be trained. We moved past a chaplain speaking softly to a young man who stared into the air like he was trying to find a window.

Inside a dim room that had once been someone’s living space, I found the lieutenant leaning over a map with two other men. A lantern threw a warm circle on the paper, making the edges of the room feel farther away than they really were.

“Callahan,” the lieutenant said. “You hear the word?”

“No, sir.”

He pointed at the map. “At first light, we move out.”

I felt my stomach tighten, not from fear exactly, but from the seriousness that comes with direction. After being pinned, being ordered to move almost felt strange—like someone telling a statue to start walking.

“Where to?” I asked.

He tapped a line beyond the town. “We’re pushing to widen the corridor. Keeping the roads open. If they choke us again, it all starts over.”

That was Bastogne in a sentence: keep the roads open or pay for the lesson twice.

The lieutenant’s eyes flicked up. “And Callahan?”

“Yes, sir?”

He hesitated, then softened his voice. “It’s New Year’s Eve.”

I didn’t know what he meant at first.

Then I saw it: the human part of his face, the part that remembered we were more than coordinates.

He reached into his pocket and produced a small object—a tin cup, dented and blackened, the kind that had lived a hard life already. He set it on the table.

“Tell the boys,” he said, “that at midnight we’re doing it proper. Not fancy. Just… together.”

I nodded. “Yes, sir.”

When I got back to our position, Lenny raised an eyebrow. “What’d the map say? We winning?”

“Map says the map’s still there,” I said. “We move at first light.”

Lenny let out a slow breath. “Of course we do.”

I relayed the midnight message, and it traveled faster than any official order. Men who had barely spoken all day started rummaging in pockets and packs. Somebody found a small stash of coffee. Somebody else produced a piece of chocolate like it was contraband. A medic traded two cigarettes for a handful of sugar packets. Nobody asked where he got them. We all understood the economy of survival.

As the evening crawled closer to midnight, the town seemed to hold its breath. The cold sharpened. The wind ran fingers through broken beams and empty windows, making the ruined buildings sing in low, uneasy tones.

I found myself thinking about home, not in a sentimental way, but in flashes: a kitchen table, my mother’s hands, the sound of a radio playing big band music like the world was still dancing somewhere. My dad had told me before I shipped out, “Whatever happens, keep your name clean.” At the time I’d thought he meant my reputation. Now I understood he meant my soul.

Near 11:30, Lenny nudged me. “Hey,” he said. “You got anything to say at midnight?”

I snorted. “Like a speech?”

“I don’t know,” he said, shrugging. “You’re the radio guy. You talk to the air.”

“I mostly listen to it,” I said.

He grinned. “Then listen hard. Maybe it’ll tell you what to say.”

Around us, men gathered in small clusters, shoulders pressed close, not out of romance, but out of heat. The tin cups made their way around, passed hand to hand like a ritual. Someone produced a battered pocket watch and declared they’d trust it more than any official clock.

At 11:59, the chaplain stepped near us. He didn’t preach. He didn’t perform. He simply stood, breath visible, eyes kind.

“Gentlemen,” he said softly, “we’ve made it to the edge of another year.”

No one cheered. We weren’t in the mood for cheering.

But we were in the mood for meaning.

Then—somehow—somebody produced a scrap of paper.

It was folded twice, then twice again, and handled like it might fall apart if you looked at it too hard. The runner who’d found it said it had been picked up near a blown-out mailbox. No name on it. No address that made sense.

Just a line written in careful English, like someone had practiced.

“If you are here, please remember: Bastogne is not only a place. It is proof.”

I stared at those words until they blurred.

Lenny swallowed. “Who wrote that?”

I shook my head. “No idea.”

The mystery of it hit me harder than the cold. A note with no signature, as if the town itself had spoken through someone’s hand. A message meant for whoever still stood.

The pocket watch ticked like it was counting more than seconds.

Ten… nine… eight…

We didn’t have fireworks. We didn’t have music. We had breath and boots and the faint metallic taste of winter.

Seven… six… five…

The chaplain raised his tin cup. The lieutenant did too. So did Lenny, and I followed.

Four… three… two…

I thought of that one-word reply that had become our backbone—Nuts—and how it wasn’t just defiance. It was identity. It was the refusal to let fear write the ending. Quân Đội Mỹ+1

One…

For a moment, nobody spoke.

Then Lenny said, quietly, almost surprised by his own voice, “Happy New Year.”

A few men echoed it. Not loud. Not celebratory.

But real.

We took a sip of coffee that tasted like smoke and hope. We passed the cup. We held the silence like it was something precious.

And then—this is the part people don’t talk about in the big speeches—the night continued.

There was no magical transformation. The front didn’t pause because a calendar page flipped. The cold didn’t apologize. The world didn’t suddenly become safe.

But something shifted anyway.

Maybe it was the simple fact that we were still there.

Still standing.

Still able to share a tin cup and a scrap of paper and a few words that meant: we haven’t been erased.

Not long after midnight, I stepped away from the group to check my set. The radio hissed, then caught a signal. A voice crackled through—faint, clipped, calm.

“…hold the roads… keep the corridor open…”

I acknowledged, sent the reply, and let the headset rest around my neck. In the distance, the horizon had the faintest hint of light, like the sky was testing whether it was allowed to brighten again.

Lenny walked up beside me and stared toward the pale edge of dawn.

“You think we’ll ever be normal again?” he asked.

I considered it carefully. “I think,” I said, “we’ll be something else. And maybe that’s okay.”

He nodded slowly. “You still got that note?”

I tapped my pocket. “Yeah.”

“Good,” he said. “Feels like… a piece of the town is coming with us.”

At first light, we formed up.

Not in a triumphant parade, not in a movie march, but in the quiet, determined way men move when they know their work isn’t finished. We stepped out of Bastogne past broken stone and snowdrifts, past the crossroads that had been the reason for everything.

Somewhere behind us, the town sat battered but unbroken—proof, exactly as the note said. Wikipedia+1

As we walked, I looked at the backs of the men ahead of me—coats stiff with cold, helmets dusted with snow, shoulders set like they were carrying more than gear.

I realized then that “Nuts!” wasn’t only a reply to an ultimatum.

It was a way of stepping forward when the odds tried to teach you a lesson.

It was what you said to a winter that wanted you to quit.

It was what you said to a circle closing in.

It was what you said to the fear that whispered, This is too much.

And on that dawn—New Year’s Day, 1945, barely lit and still bitterly cold—we said it without speaking.

We just kept moving.

Because Bastogne wasn’t only a place.

It was proof.

And proof, once made, doesn’t disappear.