“My Son Would Be Your Age” — A German Prisoner Said It, Then a Young Guard Found the One Item That Proved the Man’s Secret Wasn’t About War at All

The first time Private Caleb Mercer heard the sentence, it didn’t land like a confession. It landed like a pebble tossed into still water—small, harmless, almost polite—until the ripples touched everything.

It was late afternoon at Camp Redwillow, a POW camp tucked behind a belt of pine and scrub in the American South, where the air smelled like dust, sap, and ironed canvas. The sun dragged itself low and heavy, painting the guard towers a tired orange. Caleb had been on the perimeter walk for three hours, boots scuffing the same path, eyes following the same lines: wire fence, watch posts, barracks, the sand table near the mess hall where men played checkers with carved pieces and tried to look like they weren’t counting days.

Caleb was nineteen, lean as a fence post, with hair that refused to stay under his cap and a face that still looked like it belonged in a high school yearbook. He’d enlisted fast, like you did when you wanted to outrun something—though he couldn’t have told anyone what, exactly, he was outrunning. Maybe the hollow quiet of his mother’s kitchen after the telegram came. Maybe the way the town started speaking softer around him, like grief was something contagious.

His orders were simple: watch, report, keep distance.

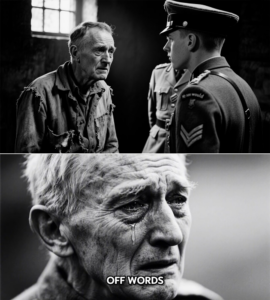

Then he saw the German prisoner standing alone near the wash station, sleeves rolled to the elbow, scrubbing a tin cup as if it were fine china. The man was older than most in the compound—mid-forties maybe—with a posture too straight for someone who had spent months behind wire. His hair was dark but threaded with gray, his hands raw and cracked. He didn’t look up when Caleb approached. He seemed to sense him the way you sensed weather changing.

Caleb slowed. “Back to barracks,” he said, because that’s what the rulebook would want him to say.

The man turned the cup in his hands, letting the water run off. When he finally raised his eyes, they were an unsettling calm, like a lake that had already learned every storm.

He spoke English carefully, with the patient accent of someone who’d learned it long before any uniforms came into play.

“Your face,” the prisoner said, not as an insult, not as a compliment—just as a fact being examined. “My son would be your age.”

Caleb felt heat climb his neck. “Move along,” he said, sharper than necessary.

The prisoner didn’t move right away. He dipped his head once, respectful. “Yes. Of course.” Then he stepped away, cup in hand, disappearing into the nearest barracks with the quiet obedience of a man who knew exactly how much attention he could afford.

Caleb kept walking, but the sentence followed him like a shadow that didn’t match his steps.

Later, in the guardhouse, the other soldiers played cards and drank weak coffee. Someone complained about the heat. Someone else said the German cooks made better bread than the camp kitchen ever had. Laughter rose and fell, easy and careless.

Caleb sat at the edge of it, pretending to check the logbook. He tried to imagine the prisoner’s son. A German boy. Somewhere across an ocean. Same age as him. Same face?

The thought irritated him, as if it were a trick.

“Mercer,” Sergeant Pruitt called, snapping him out of it. “You’re on detail tomorrow. Barracks inspection. Keep it clean, keep it calm.”

“Yes, Sarge.”

Pruitt’s tone softened, almost kindly. “Don’t get chatty with them. Some of those fellas can wrap words around your head like rope.”

Caleb nodded, but he wasn’t sure words were the danger. He was starting to think the danger was what words could wake up.

That night, he dreamed of a boy standing at the far end of a long table. The boy’s face was blurred, like a smudged photograph. But when the boy spoke, he used the prisoner’s voice.

My son would be your age.

Caleb woke before dawn with his heart punching the inside of his ribs.

The next day’s inspection started ordinary and ended strange.

Barracks C had the same stale smell as the others—soap, sweat, damp blankets. Prisoners stood in neat lines while guards checked bunks and footlockers. Most men stared straight ahead, their expressions trained into neutrality.

Caleb moved down the row with Corporal Ellis beside him. They flipped mattresses, tapped floorboards, scanned faces. Caleb tried not to look too closely at anyone, but it was impossible not to notice how the older prisoner—Barracks C, third bunk from the back—stood with his hands folded behind him like a teacher awaiting an exam.

A tag on the bunk frame read: Keller, Matthias.

Caleb didn’t know why the name mattered, but it did.

Ellis opened Keller’s footlocker. Inside were the usual items: folded clothes, a bar of soap worn to a crescent, a small German-English dictionary with a cracked spine. Ellis shifted things around, then frowned.

“What’s this?”

He held up a simple wooden box, no larger than a man’s palm. The lid had been carved with a pattern of thin lines that spiraled inward, like a slow whirlpool.

Keller’s face didn’t change. “It is mine,” he said.

Ellis shook it near his ear. Something inside clicked gently, not like metal, more like beads or seeds.

“Open it,” Ellis ordered.

Keller’s jaw tightened—only slightly, but Caleb saw it. The man took the box carefully, as if it contained something living. He lifted the lid.

Inside lay a small harmonica, tarnished but cared for, wrapped in cloth. Beneath it was a photograph, folded twice.

Ellis snatched the photo and unfolded it. Caleb saw it at the same time.

A young woman sat on a wooden bench, smiling faintly. Beside her stood a boy of about seven, hair light, eyes bright. The boy held a toy airplane in one hand and wore a flat cap that shadowed his forehead.

Ellis shrugged. “So?”

Keller didn’t look at Ellis. His eyes had locked on Caleb, and for the first time, the calm in them wavered.

Caleb stared at the boy in the photograph.

The boy’s left ear stuck out a little at the top, just like Caleb’s did. The boy had the same narrow chin, the same stubborn line of mouth.

And on the boy’s cheek—faint but unmistakable—was a small crescent-shaped scar.

Caleb’s fingers rose to his own face without thinking. He touched the scar he’d had as long as he could remember, the one his mother always blamed on “a fall when you were little.”

His throat went dry.

Ellis folded the picture back up and tossed it into the box. “Keep your sentimental junk. Just don’t hide anything you shouldn’t.” He moved on to the next locker, bored already.

But Keller remained still, holding the box like a fragile truth.

Caleb tried to speak and failed. The room suddenly felt too small, airless.

Keller’s voice came low, private, meant only for him.

“Now you understand why I looked at you.”

Caleb forced his legs to move. He stepped closer, close enough that he could smell soap and woodsmoke on the man’s clothes.

“That picture,” Caleb whispered, careful not to let Ellis hear. “Where was it taken?”

Keller blinked once, slowly. “In Hamburg. Before everything became… broken.”

Caleb’s mind raced, grabbing at facts like loose boards. “That boy—your son—what’s his name?”

Keller hesitated. “Jonas.”

Caleb’s pulse thudded in his ears. “And the scar?”

Keller’s mouth tightened, pain and memory crossing his face like a passing cloud. “He fell. He tried to climb the fence behind our building. A nail caught him. He was brave about it. Too brave.”

Caleb felt dizzy. I fell when I was little. That was what his mother always said.

He swallowed hard. “How old is your son now?”

Keller’s eyes stayed on Caleb’s. “Nineteen. If he is alive.”

The words hung there, heavy and careful. Not a plea. Not an accusation. Just a fact with sharp edges.

Caleb stepped back like he’d been pushed. “That’s… that’s not possible.”

Keller nodded once, as if he’d expected the denial. “It feels impossible. Yet—” He lifted the box slightly. “This feels possible too, yes?”

Caleb didn’t answer. He couldn’t.

For the next week, Caleb avoided Barracks C.

He did his shifts. He ate his meals. He laughed when the others laughed. But he moved through the camp as if there were a thin pane of glass between him and everything else, and behind the glass something kept rearranging the world.

At night, he stared at the ceiling of his bunk in the guard barracks, listening to crickets and distant train whistles. He tried to remember his earliest memories. They were mostly fragments: a woman’s hands fixing a collar, the smell of flour, a lullaby in a language he couldn’t name. He’d always assumed those were childhood distortions. Now he wasn’t so sure.

He thought about his mother—Ada Mercer—who’d raised him alone after his father “died in an accident” when Caleb was too young to remember. She was a steady woman, stern when she needed to be, soft when she thought no one was watching. She worked the general store, kept a garden, mended everything twice before replacing it. She didn’t talk about the past unless asked, and even then she spoke around it like it was hot.

Caleb had never questioned her. Not really.

Then one evening, as the camp settled and shadows stretched long, Caleb found himself walking toward the fence line near the wash station.

Keller was there again.

Not waiting—Caleb could tell he hadn’t been expecting anyone. He was seated on an upturned crate, harmonica in hand, playing softly. The tune was simple, a slow line of notes that seemed to carry more longing than sound.

Caleb stopped a few feet away. “You can’t play outside the barracks after lights,” he said automatically.

Keller lowered the harmonica. “I will stop.”

He didn’t move right away. Neither did Caleb.

Finally Caleb said, “Why are you carrying that photo?”

Keller glanced down at the wooden box. “It is the only proof my life existed before I became only a number behind wire.”

Caleb’s voice came rough. “That boy in the picture… he could just look like me.”

Keller’s expression didn’t turn hopeful. It turned gentler, as if he had no interest in forcing belief.

“Yes,” he said. “He could. Many people look like other people. The world is full of repeating faces.”

Caleb exhaled, almost angry at the calm. “So why say it to me?”

Keller considered. “Because when you walked past, my heart did something foolish. It remembered.”

Caleb swallowed. “What else do you remember?”

Keller’s eyes lifted to the sky beyond the wire, where the first stars were beginning to show. “I remember a small apartment. A woman singing while she washed dishes. I remember my son making airplanes from paper. I remember the sound of his feet running down the hallway, and how the world felt safe when he laughed.”

Caleb felt his hands curl into fists. “And then?”

Keller’s face tightened. “Then the world stopped being safe. There were rules. There were uniforms. There were men who believed they owned tomorrow. I tried to keep my family small, hidden, untouched. But war does not respect small things.”

Caleb’s throat burned. “What happened to your wife?”

Keller looked down, and when he spoke his voice was quieter. “I do not know. Letters stopped. Neighbors disappeared. The city changed. When I was sent away, I thought my family would be safer without me. Perhaps it was a lie I told myself.”

Caleb stared at the fence. The wire looked sharper than it had yesterday.

Keller lifted his gaze again. “You have a mother?”

Caleb nodded, stiffly.

Keller hesitated. “Ask her about the scar.”

Caleb’s breath caught. “You don’t get to tell me what to ask.”

Keller accepted that with a slight nod. “You are right. Forgive me.”

There was a pause, filled with crickets and distant voices.

Then Keller added, almost as if it cost him to say it, “I do not want anything from you. Not comfort. Not favors. Not promises. I only want to know, before I die, whether my son lived.”

Caleb’s eyes stung, and it made him furious—at Keller, at himself, at the camp, at the quiet cruelty of time.

He turned away abruptly. “Go inside.”

Keller lifted the harmonica again, but he didn’t play. He simply watched Caleb walk off as if he were watching someone disappear into fog.

Three days later, Caleb took leave.

He rode the bus back to his hometown with his cap pulled low, watching fields pass like slow waves. He tried to rehearse what he’d say to his mother, but every sentence sounded like betrayal.

When he stepped into the general store, the bell over the door chimed. Ada Mercer looked up from the counter, relief softening her face.

“Caleb,” she said. “You didn’t say you were coming.”

“I got leave,” he said. His voice sounded too flat even to him.

She came around the counter and hugged him tight, the way she always did—like she needed to prove he was real.

Then she pulled back and studied him, eyes narrowing slightly. “What’s wrong?”

Caleb swallowed. “I need to ask you something.”

Ada’s hands stilled. “Ask.”

He gestured toward the back room. “Not out here.”

They went behind the store, where sacks of flour were stacked and the air smelled of soap and cinnamon. Ada crossed her arms, bracing herself.

Caleb stared at her for a long moment, then reached up and touched the crescent scar on his cheek.

“You always said I got this from a fall.”

Ada’s face went very still. “You did.”

Caleb’s voice trembled despite his efforts. “Where?”

“In the yard,” she said quickly. “On the fence. A nail.”

Caleb’s stomach dropped. “How did you know it was a nail?”

Ada’s lips parted, then closed again. Her eyes flicked to the floor, then back to him.

Caleb pulled a folded scrap of paper from his pocket. He’d copied Keller’s name from the bunk tag: Matthias Keller.

He held it out like evidence in a trial. “Do you know this name?”

For a second, Ada looked like she might deny it. Then something in her face broke, not dramatically—quietly, like a thread snapping under too much strain.

She sank onto a stool.

“Oh, Caleb,” she whispered.

Caleb’s heart hammered. “Tell me.”

Ada stared at her hands. Her voice came slow, each word chosen like it might cut.

“During the first year of the war, I volunteered with a church group overseas. It wasn’t glamorous. We helped families find food. We translated. We carried messages. The city was… frightened.” She swallowed. “There was a boy. His name wasn’t Caleb then.”

Caleb’s mouth went dry. “Jonas.”

Ada flinched, as if the name itself had weight.

“Yes,” she said softly. “Jonas.”

Caleb’s knees felt weak. He gripped the edge of a shelf. “He was me.”

Ada’s eyes filled. “You were so small. Too small to understand why grown people were whispering, why the streets were full of noise at night. Your mother—your German mother—was gone by then. No one could find her. Your father…” She hesitated, pain tightening her voice. “Your father begged me to take you. He said it was the only chance.”

Caleb’s vision blurred. “He begged you.”

Ada nodded, tears slipping down her cheeks. “He pressed a wooden box into my hands. He said, ‘Keep this safe. If he lives, he will want to remember.’ I promised I would return you after things settled.” Her voice cracked. “But things didn’t settle. They got worse. The roads closed. People vanished. And then there was no way back.”

Caleb’s breath came ragged. “So you… brought me here.”

“I did,” Ada whispered. “I changed your name because I was terrified someone would come for you. I told myself it was mercy. I told myself it was love.” She looked up at him, pleading. “And it was, Caleb. It was. But it was also fear.”

Caleb stared at her, a storm of emotions colliding: gratitude, fury, heartbreak, confusion.

Then he asked the question he was most afraid to ask.

“My father,” he said, voice thin. “Is he alive?”

Ada shook her head, sobbing quietly. “I didn’t know. Not for years. I searched when I could. Letters came back unopened. Names were lost. And then… I thought it was kinder to stop digging at the wound.”

Caleb pressed his fists to his eyes. When he lowered them, his voice was hoarse.

“He’s in a camp,” he said. “Here. In America. Under my rifle.”

Ada’s face drained of color. “No.”

Caleb nodded once. “He recognized me.”

Ada covered her mouth. For a long moment, neither of them spoke. The back room felt too small for the truth now sitting between them.

Finally Ada whispered, “What will you do?”

Caleb stared at the flour sacks, the broom in the corner, the ordinary world that suddenly felt like a costume.

“I don’t know,” he admitted. “But he deserves to know his son lived.”

Ada’s eyes squeezed shut, and when she opened them, something steadier was there.

“Then you tell him,” she said. “And if you want… I will write him. I will tell him what I did, and why. He can hate me if he must.”

Caleb’s throat tightened. “He doesn’t have much time for hate,” he said quietly. “None of us do.”

When Caleb returned to Camp Redwillow, the air felt different, as if the trees themselves had learned a secret.

He asked Sergeant Pruitt for a private moment with Prisoner Keller under the pretense of translating—Caleb’s grandparents had been immigrants, which had always earned him odd jobs with language, though he’d never considered it important.

Pruitt grunted. “Five minutes. And Mercer—don’t get strange.”

“Yes, Sarge.”

Caleb found Keller near the wash station again, as if the universe had decided that was where truths should be spoken.

Keller stood when Caleb approached, hands at his sides, careful.

Caleb’s heart pounded so hard it almost drowned his words.

“My mother,” Caleb said. “My American mother—she was overseas early in the war. Helping families.”

Keller’s face went still. Not hope—never that easy. Just attention sharpened into something fierce.

Caleb swallowed. “She knew a boy. A boy named Jonas.”

Keller’s breath caught, just once.

Caleb continued, voice trembling. “That boy was me.”

For a moment, Keller didn’t move at all. He looked like a man trying to decide whether a bridge was real before stepping onto it.

Then his hands rose, slow and unsure, as if reaching for something sacred.

He whispered, “Jonas?”

Caleb nodded. “I didn’t know. I swear I didn’t know until now.”

Keller’s eyes filled, but the tears didn’t fall right away. When they finally did, they came quietly, almost respectfully, as if the man refused to make a spectacle of joy or grief.

He stepped forward—only one step, stopping at the boundary the guards enforced with instinct and training.

“My son,” he said, voice breaking. “My son lives.”

Caleb’s own eyes burned. “Yes,” he managed.

Keller’s mouth trembled into something that wasn’t quite a smile and wasn’t quite sorrow.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out the wooden box with the harmonica. His fingers shook as he opened it, revealing the folded photograph again.

He held it out toward Caleb. “Then it belongs to you.”

Caleb didn’t take it immediately. He stared at the image—at the boy who had been him, the woman who might have been his mother, the life that had existed and then been cut away and stitched into something new.

“I think,” Caleb said carefully, “it belongs to both of us. For now.”

Keller nodded, as if that answer made sense in a world that rarely did.

Caleb glanced around. The other prisoners were keeping distance. The guards were pretending not to listen. The sky overhead was wide and indifferent.

Caleb lowered his voice. “My mother… she wants to write you. To tell you everything.”

Keller closed his eyes for a moment, and when he opened them, his gaze was steadier.

“I would like that,” he said. “Not to punish her. Not to forgive too quickly.” He exhaled. “Only to understand.”

Caleb nodded.

Keller lifted the harmonica to his lips. “May I play?”

Caleb hesitated, then gave a small nod. “Quietly.”

The tune that came out wasn’t triumphant. It wasn’t sad either. It was something in between—something that sounded like two timelines trying to meet without tearing.

Caleb stood there and listened, feeling the wire fence behind him, the watchtower above him, and the strange, impossible truth sitting in the space between a guard and a prisoner.

When the song ended, Keller lowered the harmonica.

“My son would be your age,” he said softly, as if repeating the sentence now made it complete.

Caleb swallowed against the tightness in his throat.

“I am,” he replied.

And for the first time since he’d arrived at Camp Redwillow, the line between duty and humanity didn’t feel like a wall. It felt like a door—still heavy, still guarded, but no longer locked.

In later years, when papers were unsealed and names were sorted back into their rightful places, there would be no headline large enough for what happened behind the wire at Camp Redwillow. No grand ceremony. No neat ending.

There would only be a wooden box, a harmonica that still worked if you breathed carefully, and a photograph folded twice—proof that a life had existed before it was divided.

And there would be one sentence, passed from a German father to an American guard like a match struck in darkness:

My son would be your age.

A sentence that didn’t start a fight.

A sentence that started a memory.