MacArthur Crossed the 38th Parallel—and a Locked Kremlin Folder Opened at Midnight: The Chilling Line Stalin Sent to Beijing Under the Name “Filippov,” the One Sentence His Aides Wouldn’t Repeat Out Loud, and the Quiet Chain Reaction It Lit Across Korea and China

1) The Map That Didn’t Blink

The map room always smelled the same—paper dust, stale tobacco, and a faint metallic bite from the radiators that never quite warmed the corners. The lights were too bright for midnight, too flat for mercy. When the door closed, the silence pressed in like a hand.

Pavel Orlov stood at the edge of the long table with the others and kept his face still, as he’d been trained. If you worked near the wires—near the cables that carried secrets—you learned quickly that the most dangerous thing you could do was look surprised.

On the wall, Korea was pinned beneath glass. A thin line cut the peninsula like a scar: 38°. Someone had marked it with a red pencil months ago, confident the world would obey a ruler’s neat geometry.

Tonight, the line looked foolish.

General MacArthur’s troops—United Nations troops, Americans and allies—were crossing north. Not in theory, not as a rumor. In movement, in trucks, in boot-steps. The decision was being written into history with the same force used to write anything else in wartime: momentum.

Pavel didn’t know the exact time the first American patrol stepped over. Nobody in this room cared about patrols.

They cared about what the crossing meant.

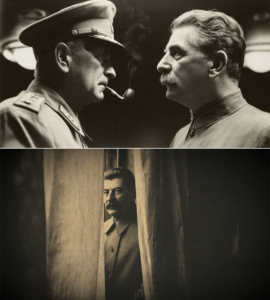

Stalin stood near the table, his posture calm, his expression almost bored. He let the others talk first—advisers murmuring about logistics, distances, what could and could not be denied. He listened in that unnerving way he had: eyes half-lidded, fingers resting near his pipe, as if the world were explaining itself and he was deciding whether it had earned the right.

Then he looked up at the map again.

“Several places,” he said, quietly.

It wasn’t a question. It was the beginning of one.

Pavel’s job was to translate sound into certainty—dictation into cipher, cipher into transmission. He was stationed here because he could keep his hands steady.

But in that moment, he felt the room tilt, just slightly, as if the building itself understood what had changed.

A line on a map had been crossed.

Now the room had to decide what kind of world came next.

2) “From Comrade Filippov”

The telegram began as most dangerous things did: politely.

Pavel sat at the small desk near the communications apparatus while a senior aide dictated, and the words appeared on paper in Pavel’s own neat script before they vanished into code. He recognized the template—destination, routing, the formal address to the Soviet ambassador in Beijing for Mao Zedong.

Then the signature line.

Not Stalin.

PHILIPPOV.

A name used like a curtain.

Pavel wrote it without blinking. Everyone in the room knew who stood behind the curtain. Nobody said it out loud.

The message’s heartbeat was blunt and immediate: Stalin was asking Mao for a minimum of “five-to-six” Chinese volunteer divisions, because—here was the phrase that made the room go colder—the enemy had already crossed the 38th parallel in several places. commonprogram.science

Pavel felt his throat tighten. It was one thing to watch armies move on a map in charcoal and rumor. It was another thing to see the crossing named in a document meant for the highest hands.

Stalin’s reasoning followed in numbered points, clean as a ledger: the United States was “not ready at present for a big war,” Japan’s militarist strength was not restored, and therefore pressure might force concessions that patience would never win. commonprogram.science+1

The language was almost casual—strategic confidence delivered with the calm of a man discussing the weather.

But then Pavel reached the line that made the aide pause before dictating it, as if even the air needed permission.

“Should we fear this?” the aide read, voice low.

A beat.

“In my opinion,” the aide continued, “we should not.” commonprogram.science+1

Pavel’s pen scratched across paper.

He had seen many kinds of courage in documents—boasting courage, desperate courage, ceremonial courage. This was another kind: the courage to gamble with consequences and call it calm.

When the dictation ended, Pavel rose with the coded sheet and carried it to the operator. His steps were measured. His face was blank.

Inside his skull, the sentence repeated like a metronome:

We should not.

The operator fed the message into the system—clicks and pulses that turned ink into distance.

Beijing would receive it. Mao would read it. And somewhere beyond the paper, men in uniforms would shift their weight from one foot to another, because words like these changed where armies stood.

3) The Reply That Wasn’t a Yes

The return message from Beijing did not arrive with drama. It arrived with delay—hours that felt like days. When it finally came, Pavel was summoned back to the map room, where faces looked slightly tighter than before.

Mao’s reply, as Stalin described it later, was not the answer the Kremlin wanted. It carried caution: the fear of widening the conflict, the concern about China’s readiness, the worry that war would cause dissatisfaction at home. commonprogram.science

Pavel watched Stalin as the words were read aloud.

Stalin did not explode. He did not shout. He simply listened, expression unreadable, and then he began composing his next move the way other men might fold a napkin—precise, almost leisurely.

“Tell him,” Stalin said at last, “that I understand the internal situation.”

A pause.

Then, with a mildness that made it more chilling, he added: “But remind him what comes if Korea becomes a bridgehead.”

Pavel’s hands did not shake as he prepared the follow-up transmission. He’d learned that the most dangerous moments were not the loud ones. They were the quiet ones, when decisions slid into place like locks turning.

In the draft Stalin sent, there was a blunt logic: if war was inevitable, better now than later—before Japan rearmed, before the United States and its allies had a stable base on the continent. commonprogram.science

Pavel copied the line carefully, aware he was holding something that might one day be quoted in books, if it ever survived secrecy.

He thought of the 38th parallel again.

A thin line. A thin line that had just pulled three capitals into the same room, without any of them meeting face to face.

4) The Letter to Pyongyang No One Was Allowed to Keep

On October 7, Mao’s position began to shift toward agreement—solidarity with Stalin’s “fundamental positions,” with a promise of divisions—though timing and details remained in motion. commonprogram.science

The Kremlin moved quickly. Another message went out—this time not just to Beijing.

Pyongyang.

Kim Il Sung.

And there, in a letter delivered through Soviet channels, Stalin’s tone hardened into instruction. The words were almost stark in their simplicity: Kim must “stand firm” and fight for “every tiny piece” of land, build reserves, strengthen resistance. commonprogram.science

But the most telling line in that letter was not military.

It was procedural.

Kim could copy the letter by hand—but he could not be given the paper itself. It was “extreme confidentiality.” commonprogram.science

A secret passed like contraband, even among allies.

Pavel imagined Kim Il Sung bent over a table, copying Stalin’s words letter by letter, the way a student copies a teacher’s lesson. A leader forced, for a moment, into the posture of a clerk.

He wondered if Kim felt honored—or trapped.

Perhaps both.

Outside, the world kept moving. The United Nations—backed by a General Assembly resolution on October 7, 1950—pressed its forces north with the political wind at its back. digitallibrary.un.org+1

And in Moscow, behind heavy doors, Stalin’s words raced ahead of armies like invisible scouts.

5) The Sentence Nobody Wanted to Own

Days later, Pavel found himself alone at the desk, waiting for the next cable. The room around him ticked with equipment. Somewhere far away, a train horn sounded—a long, mournful note that felt out of place in a capital that tried to sound invincible.

He pulled a scrap of paper from his pocket—blank, harmless—and wrote a single sentence on it from memory.

“Should we fear this? In my opinion, we should not.”

He stared at it.

It was a simple sentence. Almost conversational.

And yet it carried an entire philosophy: that risk could be managed by will, that escalation could be stared down, that history could be forced into shape like hot metal.

Pavel folded the scrap twice and slipped it back into his pocket, then immediately regretted it. Keeping such a thing—even privately—felt like carrying a spark in your coat.

He told himself it was nothing. A line. A thought.

But he had seen enough to know that lines on paper were never just lines.

They became orders. They became routes. They became graves or homecomings, depending on where they landed.

That evening, a colleague leaned in while Pavel checked the wire logs.

“Do you think he meant it?” the colleague whispered, not daring to say Stalin’s name.

Pavel did not look up. “He wrote it,” Pavel said.

“That’s not what I asked.”

Pavel’s fingers paused.

Then he said, carefully, “When a man like that writes something down, it’s because he wants the world to behave as if it’s already true.”

His colleague swallowed and stepped away.

6) The Quiet Chain Reaction

In the weeks that followed, the chain reaction unfolded like dominoes in fog.

MacArthur’s push north made Beijing feel the border’s breath. Mao weighed the costs of intervention against the costs of not intervening. Soviet support was promised and managed with its own careful limits, always mindful of direct confrontation. commonprogram.science+2commonprogram.science+2

Nothing about it looked inevitable in the moment. It looked like improvisation—decisions made on thin information, under thick pressure.

But Pavel knew better.

He had watched the first domino tip in the map room, when Stalin looked at the 38th parallel and decided that a line on a map could not be allowed to become a permanent platform for America near the Soviet Far East.

That was what Stalin was really saying, Pavel realized—not only in numbers and bullet points, but in the choice of what to fear and what not to.

Fear was a tool. Not a master.

The map on the wall changed as pins moved. Threads were redrawn. The neat pencil line remained, but it no longer behaved like a boundary. It behaved like a memory.

One night, much later, Pavel overheard an officer mutter something while staring at the peninsula’s north end—near the Yalu River, where the world narrowed toward China.

“It was always going to turn,” the officer said, half to himself. “It was always going to turn the moment they crossed.”

Pavel kept walking. He didn’t correct the officer.

Because he had learned something working near the wires: people preferred stories that sounded fated. Fate was comforting. Fate suggested nobody could have done otherwise.

But Pavel had seen the truth hiding behind code names and formal greetings.

The truth was smaller, sharper, and more frightening:

History often hinged on a sentence delivered at midnight—signed “Filippov”—and on whether the men who read it chose to believe the confidence was real.

7) The Last Look at the Line

On a cold morning when the sky looked scrubbed raw, Pavel returned to the map room for the first time in weeks. The table was clear. The chairs were empty. The air smelled cleaner, as if even tobacco had been ordered to stay quiet.

The Korea map still hung beneath glass.

Pavel leaned closer and studied the 38th parallel.

There was nothing special about it. No mountain range. No river. Just a latitude, imposed by decision years earlier, made sacred by repetition.

He thought of the telegram again—of Stalin’s calm insistence, of the way he framed risk as something to be handled, not avoided.

Pavel realized that if someone asked, years from now, “What did Stalin say when MacArthur crossed the 38th parallel?” the honest answer would not be a single theatrical quote shouted across a room.

It would be something colder and more revealing:

He said the crossing had already happened. commonprogram.science

He said America was not ready for a big war. commonprogram.science+1

And he asked a question that sounded almost gentle—then answered it with a confidence that moved nations:

“Should we fear this? … we should not.” commonprogram.science+1

Pavel stepped back from the glass.

Outside, engines turned over. Doors slammed. Men moved with purpose.

The world was already obeying the sentence.

Not because it was true in some cosmic sense—but because powerful people, in locked rooms, had decided to act as if it were.

And for Pavel Orlov, that was the most mysterious part of all:

Not what Stalin said.

But how quickly the world became the shape of his words.