“Liars!” He Shouted as the Newspaper Attacked Longstreet—Then a Young Widow’s Reply Arrived: The Chilling Final Hours of James Longstreet’s Life and the Secret He Took With Him

The news didn’t reach Gainesville like a trumpet.

It arrived the way winter news often does—quietly, carried by a cough, a worried knock, a hurried whisper at a doorway. The kind of message people repeat softer each time, as if volume could make it less true.

General James Longstreet was failing.

In the first days of January 1904, the old soldier—once Robert E. Lee’s principal subordinate, later one of the most argued-over figures the war ever produced—was nearing the end in Gainesville, Georgia.

And even then, even with his body worn down and his world reduced to a room, a window, and the sound of people speaking carefully around him, Longstreet still didn’t get what most men hope for at the end: peace and quiet.

Because Longstreet had become something bigger than a man.

He had become a battlefield.

Not the kind with trenches and cannon. The kind with ink and memory, with sermons and speeches, with “who was right” and “who delayed” and “who should carry blame.” In the years after the Civil War, as the South built a powerful mythology around Lee and the cause he represented, Longstreet increasingly became a scapegoat—especially over Gettysburg.

So while the old general struggled to breathe, the arguments around his name kept breathing just fine.

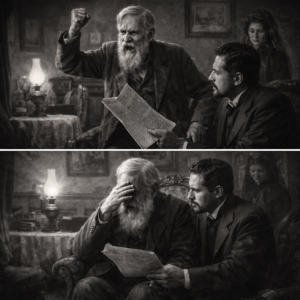

On a cold morning not far away, in a modest parlor where the fire could never quite defeat the chill, an elderly man named Gaither sat in a high-backed chair with a blanket over his knees.

His eyes were too weak now to read the newspaper. His hands shook when he tried to hold it anyway. But he had a son, and sons were good for certain things: lifting heavy objects, reaching high shelves, and—when age demanded it—lending their eyes to a father who still needed to know what the world was saying.

J. C. Gaither unfolded the paper and cleared his throat.

“Ready?” he asked gently.

His father grunted. “Read it.”

J. C. began with the article’s header, then the first lines, then the next. The prose was sharp—too sharp for a man reading it aloud in a family room. It carried the unmistakable tone of someone prosecuting a case that had already been decided in his own mind.

It was written by Reverend William N. Pendleton—once Lee’s chief of artillery, later a tireless defender of Lee’s reputation, and one of the voices who helped push a harsh narrative about Longstreet’s conduct at Gettysburg. Pendleton had famously claimed—contrary to earlier statements—that Lee ordered a sunrise attack on July 2 and that Longstreet’s “delay” was the reason the battle was lost. Wikipedia+1

The words landed in Gaither’s parlor like a slap.

The article repeated the old accusations, dressed up as certainty: Longstreet had been stubborn, Longstreet had been disobedient, Longstreet had failed Lee, Longstreet had failed “his people.”

Gaither’s face tightened as if the sentences were physical pressure.

J. C. kept reading, but he could hear his father’s breathing change.

The old man’s fingers clenched the arm of the chair.

And then—like a match struck in dry grass—Gaither snapped.

“Enough!” he shouted, voice suddenly strong. “Enough of that!”

J. C. stopped mid-sentence, startled.

His father leaned forward, eyes bright with a fierce, familiar heat.

“Again with that?” Gaither barked, shaking his head. “Again with dragging him through the mud like it’s some kind of sport?”

J. C. tried to calm him. “Pa—”

“Don’t ‘Pa’ me,” the old man cut in. “I remember the war. I remember what men were like. I remember what fear does to a person. And I remember what it looks like when people want someone to blame after the smoke clears.”

He jabbed a trembling finger at the newspaper.

“Those men talk as if they were standing behind every tree. Like they saw every order, every hesitation, every choice. They didn’t. And even if they did—who made them judges?”

His voice cracked into something raw.

“Liars,” he said. Then again, louder: “Liars!”

J. C. had heard versions of this before. His father had been through the war as a young man, and like many, he’d spent the decades after it trying to arrange his memories into a shape that didn’t hurt. Sometimes that meant defending the men he believed had been treated unfairly. Sometimes it meant defending the very idea that the war had been “understood” correctly by those who wrote the loudest.

But today was different.

Today there was something urgent under the outrage—something like grief, or maybe fear that time was running out for truth to get a fair hearing.

J. C. folded the paper slightly and softened his voice.

“Pa,” he said, “there’s another article.”

The old man blinked. “Another attack?”

“No,” J. C. said. “A reply.”

Gaither’s breathing slowed a fraction. “From who?”

J. C. glanced at the byline and hesitated as if he knew the name would change the room’s temperature.

“Helen Dortch Longstreet,” he said.

The old man’s expression shifted—surprise, suspicion, and then a reluctant respect.

“The young widow,” Gaither muttered.

“Yes,” J. C. said, and began to read.

Helen’s words were different.

Not soft, exactly. But controlled.

She didn’t roar. She didn’t spit. She didn’t speak like someone trying to win applause. She wrote like someone holding a fragile thing—her husband’s legacy—in both hands, refusing to let it be dropped and broken by louder voices.

Helen had devoted years to defending Longstreet against the harshest postwar critics. Encyclopedia Virginia

In her rebuttal, she did something that felt almost shocking in an era when public arguments often became personal: she treated even her opponents like human beings, wrong but human.

And that tone—steady, direct, almost tender—hit Gaither’s parlor harder than any insult could have.

J. C. read on.

Helen acknowledged that the war’s survivors were aging, that memories were sharpening into stories, and that stories were being repeated until they became “history” simply through repetition. She didn’t deny that mistakes were made—wars are factories of mistakes. But she insisted that one man should not be chosen as the convenient villain for a tragedy that belonged to thousands.

As the words filled the room, Gaither’s shoulders lowered.

His hands unclenched.

The heat in his face drained into something quieter.

And then, as J. C. reached a passage where Helen wrote about the general not as an argument but as a person—devoted, complicated, loyal in ways that didn’t always fit other people’s preferred scripts—the old man did something J. C. hadn’t seen in a long time.

He began to cry.

Not loudly. Not theatrically.

Just a slow, helpless leaking, like a dam finally admitting it was tired.

J. C. stopped reading, unsure what to do.

Gaither lifted one hand, palm out.

“Keep going,” he said, voice thick. “Please. Keep going.”

So J. C. did.

And the parlor, for a few minutes, became something rare: a room where a man could mourn what the war had turned people into—how it had not only killed bodies, but reshaped truth into a prize men fought over long after the shooting stopped.

That same afternoon, in Gainesville, another room held its own quiet.

Longstreet’s health had been poor for years, and by early January 1904, the end was near. Official records place his death on January 2, 1904, in Gainesville. Encyclopedia Virginia

Some later retellings—passed around like family lore—described a violent coughing fit while he was visiting one of his daughters, followed by a frightening weakness and a darkened handkerchief that no one wanted to discuss too plainly. Those retellings sometimes added that the strain might have reopened the old wound he’d suffered in the Wilderness decades earlier, as if even his own body refused to forget the war. (The details vary depending on who tells it, which is often how you can tell the story has lived a long time in people’s mouths.)

What does not vary is the atmosphere: a powerful man reduced to a fragile breath, and loved ones trying to hold normal conversation close enough to keep fear away.

Helen was there—much younger than him, yet suddenly older than her years in the way grief forces on people.

Longstreet lay propped up, eyes clouded by illness and age. His hearing wasn’t what it once was. His voice came when it could, then disappeared like a match in wind.

At some point, a nurse adjusted the blankets. Someone offered water. Someone said, “Rest, General,” with the gentle firmness of someone who had learned not to argue with the stubborn.

Longstreet’s mouth twitched.

Even now, he disliked being told what to do.

Helen leaned close. “James,” she whispered, “I’m here.”

His eyelids fluttered. A faint hint of recognition arrived.

And then—this is where the stories become almost painfully human—he said something that didn’t fit the room, as if his mind had walked into an older memory and started speaking from there.

“They’ll be happy,” he murmured. “In our new post.”

Helen froze.

The phrase made no sense and yet made emotional sense all at once.

Longstreet had lived through multiple lives: soldier, controversial public figure, writer defending his decisions, a man whose reputation became a target as much as a subject of debate. Encyclopedia Virginia

Now, at the edge of his last hours, his mind seemed to drift toward the language of duty and reassignment, as if death were simply another order—another station on the long route.

Helen blinked fast and swallowed.

“Your post?” she whispered, not correcting him, not challenging the confusion. “Yes. We’ll be happy.”

Because sometimes love means stepping into someone’s fog and holding their hand there.

Longstreet’s eyes moved slightly, searching her face.

For a moment, it was unclear whether he saw Helen—or the first wife he’d lost long ago—or some blend of both, as memory and longing braided together.

Then his expression softened.

And for a brief instant, he looked less like a figure from history and more like what he had always been underneath the uniform and the arguments:

A tired man who had carried too much for too long.

Back in Gaither’s parlor, J. C. reached the end of Helen’s rebuttal and let the paper lower into his lap.

The room was quiet except for the pop of the fire and his father’s uneven breathing.

Gaither wiped his cheeks with the back of his hand, embarrassed by the tears and yet unwilling to deny them.

J. C. hesitated, then asked, “Why does it get to you so much, Pa? You didn’t even know him.”

Gaither stared at the hearth as if it held answers.

“I knew the kind of man he was,” he said finally. “Or at least… I knew enough.”

J. C. waited.

Gaither exhaled.

“They act like the war ended and the truth stood up and dusted itself off,” he said bitterly. “But it didn’t. The war ended and then the fighting moved into words. And words can be crueler because they don’t bleed.”

J. C. swallowed. “So what now?”

Gaither’s eyes lifted—watery, tired, and clear.

“Now,” he said, “we remember that people were people. Not statues. Not villains. Not saints. People.”

He tapped the newspaper.

“That’s what she did,” he said, meaning Helen. “She wrote him back into being a man.”

J. C. nodded slowly.

Gaither leaned back in his chair, suddenly exhausted.

“Do you know what I hate most?” he whispered.

“What?” J. C. asked.

“That even at the end,” Gaither said, voice shaking again, “he couldn’t just be allowed to die without someone arguing over him.”

In Gainesville, the end came quietly.

No cannons. No marching bands. No grand last words that history could pin like a medal to a timeline.

Just the soft shuffle of footsteps, a hand squeezing another, and breath that grew thinner until it was gone.

Longstreet died in early January 1904 in Gainesville, Georgia. Encyclopedia Virginia

And even then, even after his burial, the controversies didn’t immediately die with him—because controversies rarely do. They linger, fed by pride, politics, and the human hunger for simple stories.

But Helen remained.

She outlived him by decades, continuing to argue for his place in history and pushing back against the narratives that tried to flatten him into a convenient scapegoat. Encyclopedia Virginia

And in parlor rooms like Gaither’s—small rooms with small fires and old men who could no longer read but could still feel truth in their bones—her words did something powerful.

They didn’t erase the war.

They didn’t turn tragedy into comfort.

They did something harder:

They made room for complexity.

They reminded readers that bravery can exist alongside mistakes, that loyalty can be punished by politics, and that history is often shaped not only by what happened, but by who keeps talking afterward.

Years later, J. C. Gaither would remember that day less as a lecture and more as a scene: his father’s sudden outburst, the tremble in his hands, the way his face changed when the young widow’s words entered the room.

He would remember his father’s tears most of all—because those tears didn’t come from weakness.

They came from the exhaustion of carrying a war long after it ended.

And if you want the most haunting truth of all, it might be this:

Longstreet’s last “battle” wasn’t fought with a sword or a gun.

It was fought in the memories of people who never stopped arguing about him.

Which is why his final days feel so strange and so chilling when you look back:

A dying general drifting between past and present…

A widow fighting ink with ink…

An old veteran yelling at a newspaper as if he could still change the outcome…

And a single, mysterious phrase—“happy in our new post”—floating at the edge of the room like a door half-open, hinting that even for men who live their whole lives in controversy, the last hope is always the same:

Somewhere beyond the noise, there’s finally a place where the arguments stop.