Japanese Admirals Celebrated the “Confirmed Sinkings”… Until Those Same American Hull Numbers Reappeared on Radar—Alive, Repaired, and Closing Fast—Forcing One Chilling Question That Shattered Their Confidence Overnight

The sea was calm in a way that felt disrespectful.

A flat, steel-gray sheet stretched to the horizon, as if the ocean itself had decided to hold its breath. High above, clouds drifted in long, pale bands. The kind of sky that made distances hard to judge and silhouettes easy to mistake—perfect conditions for rumors to become facts.

On the flag bridge of the light cruiser Kirishima Maru—a ship whose paint had been scrubbed so many times the metal seemed to show through—Vice Admiral Takamori stood with his hands behind his back and watched the horizon through binoculars that had been issued before he earned the right to carry them.

He wasn’t an old man, but the war had given him an older face. A narrow jaw. Deep lines carved by sleepless nights and unwanted calculations. The kind of expression that came from making decisions you couldn’t undo.

Behind him, the chart room hummed with restrained urgency—pencils scratching, radios clicking, the soft, continuous murmur of officers who knew the difference between confidence and theater.

“Message from air recon,” an aide said, stepping up with a paper strip.

Takamori did not turn right away. He waited one extra beat, as if timing mattered even in small things.

“Read it,” he said.

The aide cleared his throat. “Contact reported. Enemy task group. Multiple large hulls. Estimated bearing one-seven-five. Speed… high.”

Another officer leaned in, already reaching for the map. “Carriers?”

The aide hesitated, then said, “Recon believes so, sir.”

The word carriers hung in the air like a cold drop of water.

Takamori lowered his binoculars and finally turned, his gaze cutting across the room with a calm that made men stand straighter.

“Which ones?” he asked.

The question sounded simple. It wasn’t.

In modern naval war, names were less useful than numbers, and numbers were less useful than certainty. Every battle produced reports. Every report produced claims. And claims—especially optimistic ones—had a way of solidifying into truth before anyone verified the shape of the wreckage below.

The intelligence lieutenant, a thin young man named Sato, stepped forward from the edge of the room as if he’d been summoned by the question alone. He held a folder hugged to his chest. His uniform fit too neatly, the sign of someone who’d spent more time with paper than salt spray.

“We have partial identification,” Sato said, voice steady but careful. “From radio intercepts and silhouette comparison.”

Takamori looked at him. “Partial is not enough.”

Sato swallowed. “No, sir.”

A senior staff officer snapped, impatient. “If they’re here, they’re here. Names don’t change the sea.”

Takamori’s eyes did not move to the staff officer. He kept them on Sato.

“Try again,” Takamori said softly.

Sato opened the folder and pulled out a sketch—quick, practiced lines: an angled flight deck, a certain island structure, the faintly recognizable profile of a ship class that had haunted the navy for years.

“Our analysts believe one of the large hulls matches the carrier reported lost near the Santa Cruz area,” Sato said. “The one our communiqués listed as… unable to continue.”

The staff officer barked a short laugh. “That one? Impossible.”

Takamori’s face did not change, but something in his posture tightened.

Sato continued, carefully: “There are also escort vessels whose hull numbers correspond to destroyers we recorded as ‘confirmed’ in earlier actions.”

The room went quiet.

Not silent—radios still clicked—but quiet in the way people become quiet when the floor shifts under them.

Takamori looked down at the sketch.

He remembered the night the navy had celebrated that “confirmed” carrier result. He remembered the officers congratulating one another, the messages that flew from ship to ship like victory itself was contagious. He remembered thinking, even then, that celebration was a kind of hunger—easy to feed, hard to satisfy.

Now the hunger had teeth.

“You are saying,” Takamori said, “that ships we announced as finished are… present.”

Sato nodded once. “Yes, sir.”

A different officer—older, sharper—leaned forward. “Or recon has misidentified them.”

Sato hesitated. “That is possible.”

The older officer snapped, “Likely.”

Takamori held up a hand, and the room obeyed. He studied Sato as if measuring not the words, but the courage behind them.

“What did the recon pilot say?” Takamori asked.

Sato glanced down at the strip. “He said… the deck markings were clear enough to read through the breaks in cloud. He sounded shaken. He used a phrase: ‘It’s like the dead came back.’”

Several men shifted uncomfortably.

Superstition was a thing people pretended they didn’t believe in—until fog, distance, and war made rational life feel thin.

Takamori turned to the window. Far out, the horizon still looked empty.

But emptiness at sea was rarely empty.

“Send the destroyer screen wider,” Takamori ordered. “And bring me the latest photo intelligence from the last six months.”

Sato blinked. “Six months, sir?”

Takamori’s voice remained even. “If something can return from a place we believed it couldn’t, then the past six months are not the same as the six months we imagined.”

No one argued.

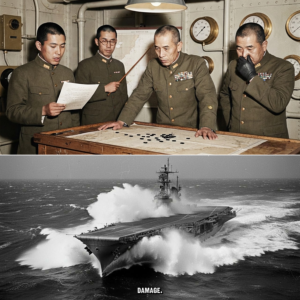

That afternoon, the first distant shapes appeared—dark smudges against the light line where sea met sky.

At first, they could have been clouds that had fallen too low. Then they sharpened, slowly, into geometry: straight lines, hard angles, movement that didn’t belong to nature.

A petty officer brought Takamori fresh binoculars. Takamori refused them. He kept his older pair.

He wanted to see through familiar lenses.

As the task group came closer, the silhouettes separated: one large ship with a long, flat profile, flanked by smaller, quick-moving escorts.

Sato stood beside him now, quiet, tense, as if he could feel his own career balanced on the accuracy of his earlier statement.

“Can you see the markings?” Sato asked.

Takamori did not answer immediately. He adjusted the focus with small, precise movements.

Then he exhaled once—soft, controlled.

“Yes,” he said.

The carrier’s flight deck markings were visible between waves of haze. Not crisp, but readable enough that Takamori’s stomach tightened.

Because it wasn’t just a carrier.

It was a specific carrier.

Not the one they had told their men was gone.

Not the one their people at home believed had been removed from the war like a piece taken off a board.

It was there—moving, steady, escorted, alive.

A staff officer behind them muttered something in disbelief. Another whispered a prayer under his breath, quickly, as if embarrassed by it.

Takamori lowered the binoculars and turned his head slightly toward Sato.

“Lieutenant,” he said, “what did our reports call this ship after the last engagement?”

Sato’s voice was thin. “They called it ‘finished,’ sir.”

Takamori nodded once, as if confirming a mathematical result.

Then he said, quietly—almost to himself—“So our words sank it. Not the sea.”

Sato looked up, startled by the admission.

Takamori’s eyes remained on the approaching formation.

He had commanded long enough to know that reality didn’t care what you wrote in a communiqué. Reality didn’t care what you told your people to keep their morale steady. Reality arrived like steel on the horizon—silent, blunt, undeniable.

Another officer stepped up, face tight. “Sir, permission to transmit to fleet command: enemy carrier confirmed.”

Takamori nodded. “Transmit.”

The officer hurried away.

Sato remained beside Takamori, as if he didn’t trust his legs.

“They repaired it,” Sato whispered, more to himself than to Takamori.

Takamori’s gaze stayed forward. “Yes.”

Sato’s brows tightened. “How? It was—our pilots reported—”

“Do not repeat the details,” Takamori said calmly. “They change nothing.”

Sato swallowed. “It feels like…” He searched for words that would not offend, not in front of senior officers. “It feels like they can lose a ship and still keep it.”

Takamori’s mouth moved, barely. Not a smile. Something closer to a grim understanding.

“They have factories,” Takamori said. “And time. And distance. Three things that are heavier than steel.”

Sato stared at the sea. “Then what do we have?”

Takamori’s answer came without hesitation.

“We have what we have always had,” he said. “Skill. Discipline. And the habit of fighting as if we must end things quickly.”

He paused, then added, “Which is not the same as winning.”

The words landed like a quiet blow.

As dusk fell, the encounter did not turn into the dramatic clash some officers expected. The fleets maneuvered, tested one another, feinted like boxers watching for an opening. Aircraft appeared in the distance like insects, then vanished back into cloud bands. The sea remained calm, indifferent to strategy.

But something did collapse.

It wasn’t the ships.

It was the certainty in the Japanese command space.

That night, Takamori sat in the chart room while the ship’s lamps cast warm circles on cold paper. The smell of ink and salt mixed in the air.

A message arrived from fleet command: requests for confirmation, repeated questions, demands for clarity.

“Are you certain it is that carrier?”

Takamori read the question twice, then looked up at Sato, who stood nearby with his folder.

Sato’s face was pale with fatigue. “They think it must be wrong,” Sato said quietly. “They think we misread it. Because… because it’s easier.”

Takamori’s gaze hardened. “Easier than what?”

Sato hesitated. “Easier than admitting our picture of the enemy is outdated.”

Takamori folded the message carefully and set it down.

In the past, naval war had been about decisive moments—big engagements that shattered one side’s strength in a day. The navy had been trained on that idea like a religion. One great strike. One great victory. A clean break.

But the enemy across the water did not seem to worship clean breaks.

They seemed to worship endurance.

And endurance was a cruel opponent. You could hit it, hurt it, even knock it down, and it would still stand back up—patched, reinforced, returned.

A staff officer entered, hesitant. “Sir… there is talk among the crew.”

Takamori didn’t look up. “What kind of talk?”

The officer lowered his voice. “They call them… ‘returning ships.’ They say the Americans are sending the same hulls again and again. They think it is… a trick.”

Sato’s jaw tightened. He looked like he wanted to argue, to defend rational analysis.

Takamori raised a hand slightly.

“Let them talk,” Takamori said.

The officer blinked. “Sir?”

Takamori finally looked up, his eyes steady. “If men must create stories to hold their fear, they will. Our job is not to scold them. Our job is to give them something stronger than stories.”

The staff officer nodded uncertainly and left.

Sato stepped closer. “Sir,” he said, “may I speak freely?”

Takamori gestured.

Sato exhaled. “When I was a student,” he said, “we studied shipbuilding. The Americans were always described as… careless. Too industrial. Too crude. We were told they couldn’t match us in craftsmanship.”

Takamori watched him, listening.

Sato’s voice sharpened with frustration. “But what I saw today was not crude. It was… organized. A kind of confidence. Like they expected to return.”

Takamori’s eyes narrowed slightly. “Yes.”

Sato swallowed. “So what do we tell fleet command? What do we say when they ask, ‘How can a ship we sank return’?”

Takamori didn’t answer right away.

He stood, walked to the small window, and stared at the night sea. Somewhere out there, the American task group moved like a steady pulse beyond the dark.

Then Takamori said, low and precise, as if dictating a report that would outlive him:

“Tell them this,” he said. “Tell them we did not understand the enemy’s true strength. Their strength is not that they never lose ships. Their strength is that loss does not remove a ship from the war if they can rebuild it. Their strength is the return.”

Sato’s throat moved as he swallowed. “And if they ask what we heard their officers say?”

Takamori’s mouth tightened. “We do not know what they said. We know what we heard in ourselves.”

He turned back to Sato.

“And what we heard,” Takamori said, “was the sound of our certainty cracking.”

Days later, in a different chart room on a different ship, another admiral—older, harsher—received Takamori’s report and read it with narrowed eyes.

He did not like it.

He wanted clean answers: We sank this, so it is gone. We struck here, so they are weaker. We suffered this, so we must strike harder.

Instead he got something messier: They return.

He slammed the paper down and barked at his staff, “This is nonsense. A ship does not return from the sea.”

But the younger officers in the room exchanged glances that said what they didn’t dare say aloud:

A ship didn’t have to return from the sea.

It only had to return from the report.

Weeks of intelligence updates followed. New photos. New hull numbers. New sightings. Again and again, the same pattern appeared: an American ship damaged, withdrawn, then months later, reappearing—sometimes with different paint, sometimes with added guns, sometimes looking even more prepared than before.

Each return was a quiet blow.

Not because the Japanese navy lacked courage.

But because courage is easier to summon against a known enemy than against an enemy who refuses to stay where you place them.

In late summer, Sato sat alone one night and wrote in his private notebook—something he did only when sleep wouldn’t come.

He wrote:

We believed war was subtraction. Remove their ships, reduce their will. But they treat war as replacement. They lose, then replace. They return.

He paused, then added, almost angrily:

How do you defeat a system that turns damage into delay instead of defeat?

The question had no clean answer.

Not then.

On the next engagement, when the lookout shouted “Enemy ships,” the officers did not celebrate early. They did not say “confirmed.” They did not say “finished.”

They spoke with a new caution, as if words themselves had become unreliable.

Takamori stood again with binoculars, scanning distant shapes. He felt older than the calendar said he was.

Sato stood nearby, silent, watching the horizon like it might betray them.

And when the American ships appeared—one of them unmistakably the same hull they had once counted as gone—Sato heard a low voice behind him.

Not a shout.

Not a dramatic cry.

Just an exhausted statement from an experienced officer, spoken as if naming the weather:

“They came back.”

Sato didn’t turn. He kept his eyes forward.

Because this time, the shock was not in the sight of steel.

It was in what the sight forced them to accept:

That their enemy did not need to be invincible.

The enemy only needed to be stubborn enough to return.

And once you realize that, everything you thought would collapse the war—one decisive blow, one perfect strike, one “confirmed” report—starts to feel fragile.

Like fog in sunlight.

Like a story that no longer matches the horizon.

Somewhere across that same horizon, the American formation moved steadily onward, engines humming, decks busy, flags snapping in wind that belonged to no one.

And on the Kirishima Maru, amid the quiet clatter of radios and the scratch of pencils, Takamori finally understood what the returning ships really meant:

Not that the Americans were ghosts.

But that the Japanese navy had been fighting an idea of the enemy that was already sinking—while the real enemy kept sailing back into view, repaired and relentless, as if daring them to try again.

And that was the moment the admiral’s confidence truly collapsed—

Not with an explosion.

Not with a dramatic surrender.

But with the slow, unmistakable realization that in this kind of war, “sunk” was not always the end of the story.