Inside the 72 Hours That Broke Japan’s Carrier Dream: A Foggy Radar Blip, a Desperate Launch, and the Dusk Landing That Changed the Pacific Forever

The sea looked calm enough to forgive anything.

That was the trick of the Philippine Sea in June—wide, blue, almost polite. If you didn’t know better, you could believe it was only water and sky, nothing else. But under that calm surface ran an invisible map of intent: arrows of fleets, circles of search patterns, thin pencil lines that meant fuel, distance, time. A whole war measured in miles of ocean and minutes of daylight.

Seventy-two hours can feel like a season when you’re living inside a carrier task force.

On the evening the clock truly started, Seaman First Class Eddie Navarro stood in the dim glow of a radar shack and watched a green line sweep a circle again and again, like a lighthouse beam trapped behind glass.

He was nineteen. He’d seen storms, he’d seen exhaustion, he’d seen men cry when mail arrived. But he had never seen an entire battle begin as a whisper.

“Anything?” the petty officer asked, leaning in.

Navarro blinked hard, forcing his eyes to stay steady. Radar fatigue was its own kind of weather. It made you doubt your senses. It made you see ships that weren’t there and miss ones that were.

“Not yet,” Navarro said.

The petty officer grunted and stepped back. Outside the radar shack, the carrier’s deck lights were lowered. The night crew moved like shadows, doing work that had to be done even when the ocean pretended nothing was coming.

Far above, stars scattered across the sky with insulting peace.

Navarro thought of home—New Mexico, dust, heat—and the idea that somewhere on land, a person could look at the same stars and have no idea how much metal and fear floated beneath them.

Then, for a breath, the screen did something strange.

A faint mark—so faint it could have been a smudge of static—blinked near the edge of the scope. It vanished. Returned. Vanished again.

Navarro leaned closer, heart tapping. He adjusted the gain. The mark sharpened into something with intent.

“Contact,” he said quietly, as if speaking too loudly might scare it away.

The petty officer snapped forward. “Range?”

Navarro swallowed. “Long,” he said. “Far out. Could be a group.”

The petty officer’s hand hovered over the headset. His voice changed—less casual, more careful. “Hold it steady,” he told Navarro. “We’ll feed it up.”

Navarro watched the blip pulse, disappear, return. He knew what it meant, even before anyone said it aloud: out there in the darkness, other engines were turning, other decks were being cleared, other crews were tightening straps and checking needles.

Not monsters. Not ghosts. Men—just like them—moving across the same ocean with a different flag and the same limited hours of fuel.

In another corner of the Pacific, in another kind of light, a Japanese naval aviator named Kazuo Sato sat on the deck of a carrier and listened to the sea.

He had learned to hear it the way you hear a person’s mood. The water against the hull told him how fast they were going, how hard the ship was pushing. The wind over the deck told him whether the next launch would feel easy or like a leap off a roof.

He was twenty-three. He carried a photograph of his mother in his flight suit—carefully wrapped to keep it dry—and a small notebook where he wrote lines of poetry he never showed anyone. He did not write about war. He wrote about skies, about clouds, about light.

Tonight, he wrote nothing.

Across the deck, ground crew moved with quick hands and tight faces. Someone laughed too loudly, the way people do when they’re trying to prove fear has no grip on them. Another man checked a fuel line twice, then a third time, then turned away as if the fuel line had insulted him.

Sato looked toward the bow. The ship’s lamps were dim. The horizon was a dark seam. His carrier—one of the last symbols of Japan’s reach—felt both enormous and fragile at once.

A junior officer walked past and paused. “Sato,” he said.

“Yes?”

The officer’s smile was polite but thin. “Sleep when you can. Tomorrow will be busy.”

“Tomorrow is always busy,” Sato replied.

The junior officer didn’t laugh. He only nodded, then moved on.

Sato watched him go, and a thought drifted through him, unwelcome and quiet: Busy is not the same as safe.

Back on the American side, the senior men argued in rooms that smelled of coffee, sweat, and paper.

In a low-lit operations space, maps were pinned. Markers moved. Voices stayed controlled, but you could hear the strain underneath, like a wire pulled tight.

Admirals did not shout when the stakes were highest. They spoke carefully, because every word could become an order, and every order could tilt the whole horizon.

“Do we push west?” one voice asked.

“We protect the landing,” another replied.

“We protect the fleet,” a third voice added.

That was the truth beneath it all. American forces were supporting a massive operation in the Marianas. The carriers were not just hunting; they were guarding something bigger than themselves. If they chased too far, they could leave the landing forces exposed. If they stayed too close, they might miss the chance to break the enemy’s carrier power for good.

Somewhere, a clock ticked.

Somewhere else, Navarro stayed at his screen, watching blips come and go like shy animals at the edge of a field.

At dawn, the ocean changed.

The first light didn’t arrive gently. It spilled over the horizon like a curtain yanked open, and suddenly everything was visible: low clouds, scattered glare on water, the pale wake of ships moving in disciplined lines.

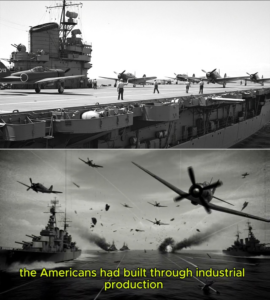

On the American carriers, flight crews moved faster. The deck crews wore colors like signals—each job marked, each man part of a machine that had to function without hesitation. Planes were rolled into position. Engines coughed awake. Propellers blurred.

Navarro wasn’t on deck, but he felt the vibration through the steel. It was like being inside a breathing beast.

On the Japanese carriers, the morning was the same—engines, checks, hand signals, faces set into professional calm. But there was something else too: urgency. A sense that time was running out faster than anyone wanted to admit.

Sato stood by his aircraft, helmet tucked under his arm. He ran a hand along the fuselage the way you might pat a horse before a long ride. The metal was cool, damp with sea air. He could smell fuel and oil and the faint bite of salt.

A mechanic caught his eye and nodded once. Not a smile. A nod that said: I did my job. Now do yours.

Sato climbed in and settled. Straps tight. Instruments checked. His world narrowed to a canopy of glass and a cluster of dials, and the wide ocean beyond.

He thought, briefly, of the word home, and how far away it had become.

Then the signal came.

The aircraft ahead rolled. The deck officer’s arms moved in practiced arcs. The engine roared louder, swallowing thought.

Sato’s plane surged forward.

The bow fell away.

For a moment, every pilot in the world knows the same feeling: the strange weightless second where the sea is below, the sky is above, and your life is balanced on machines and training and luck.

Then the aircraft caught air, and the flight became real.

Over the American fleet, radar picked up the incoming formations in time. That was the advantage of the new world: seeing farther, earlier, clearer. The faint whisper on a screen could become warning, could become preparation, could become survival.

Navarro watched contacts multiply.

He called ranges, bearings, headings. His voice stayed steady, but his palms were damp.

On deck, American fighters rose to meet the incoming wave like a lid snapping shut.

To the men in the air, it did not feel like a grand historical moment. It felt like sun glare in your eyes, radio chatter, the tightness of your own breath.

It felt like searching the sky for shapes that meant danger.

The first encounters happened far from the carriers, over open water. The sky became crowded with motion: aircraft turning, climbing, dropping. Trails of vapor. Bursts of distant anti-air pops.

Navarro only saw it as shifting marks, merging and separating.

Sato, in the middle of the Japanese formation, saw something else: a line of American fighters slicing down from above, fast and confident.

His radio lit up with voices, clipped, urgent. He heard the word for enemy, the word for altitude, the word for break. He pushed his plane into a turn, feeling the G-force press him into his seat. The horizon spun. Sea. Sky. Sea again.

He caught a glimpse of an American aircraft passing, and for a heartbeat he saw the other pilot’s canopy, a face behind glass—just a face, not a symbol. Then they were gone, each moving too fast to understand the other.

In the hours that followed, the battle became a rhythm: waves launched, waves intercepted, returns counted, fuel measured, decisions made in minutes.

On the American carriers, deck crews watched the horizon and the skies with a tension that never fully released. They counted incoming planes the way you count footsteps in a dark hallway.

On the Japanese side, the air groups thinned. Some aircraft returned damaged. Some returned low on fuel. Some did not return at all, and the empty space they left behind felt louder than any engine.

Sato made it back from his first sortie with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking. He landed hard, rolled, and stopped. Deck crew rushed in, guiding him, unhooking, pushing him into a parking spot like a man steering a wounded animal.

He climbed out and stood on the deck for a second, trying to convince himself he was still on solid ground.

An officer approached, eyes scanning him. “Damage?”

Sato shook his head. “No.”

“How many in your section?”

Sato looked past the officer, toward the landing area. Planes came in, one by one. Too few.

He forced the answer out. “Not enough.”

The officer’s jaw tightened. “Get water. Rest if you can. We launch again soon.”

Again soon. The phrase felt like a weight.

On the American carriers, the reports coming in felt different—less relief, more grim calculation. They could tell their defenses were working. They could tell the enemy’s carrier air power was being drained quickly. But they also knew a wounded opponent could still do damage, and the ocean had room for surprises.

In the evening, as day slipped toward dusk, the sea returned to looking calm.

But beneath that calm, the consequences were already taking shape.

The second day began with a new kind of tension: not just incoming raids, but the hunt itself.

American aircraft searched wider. Scouts traced patterns over the ocean, eyes scanning for the faint smudge of smoke that could betray a carrier. The sky was vast and indifferent, and sometimes it felt like looking for a needle tossed into a blue desert.

Meanwhile, on the Japanese carriers, the mood shifted from confidence to something more desperate and quiet.

Fuel was not infinite. Planes were not infinite. Trained aircrew were not infinite.

Sato sat against a bulkhead with his helmet in his lap. He listened to the ship’s engines and tried to slow his breathing.

A friend—another pilot—sat beside him, rubbing his hands together as if the gesture could warm his thoughts.

“Do you think it ends today?” the friend asked.

Sato didn’t answer right away. He could have said what officers said—duty, honor, tomorrow. But he was too tired for slogans.

“I think the sea decides,” he said finally.

His friend gave a short laugh. “The sea is cruel.”

Sato looked out through a gap in the structure and saw the ocean sliding by. It looked peaceful. It looked forgiving. That was its cruelty: it never looked like what it was.

That afternoon, American forces finally found the Japanese carriers far out, late in the day. The range was long. The light was fading. It was the kind of decision that makes commanders stare at a clock like it’s a weapon.

Launch a strike late, risk running out of daylight on the way back. Don’t launch, risk letting the enemy slip into darkness.

On the American decks, the order came.

A strike package rolled forward. Engines rose into a collective roar. Planes lifted off one after another, leaving the carriers’ decks briefly bare, as if the ships had exhaled.

Navarro, still near his radar station, heard the vibration change. He imagined the aircraft climbing into the orange edge of evening.

And out there, beyond the visible line of the world, the Japanese fleet waited—still moving, still trying to maneuver, still hoping the night would cover them like a blanket.

When the American strike arrived, the sky was already turning gold.

Sato was airborne again, because there was no time to be anything else. He climbed through thin cloud and saw the first distant shapes of incoming aircraft—dark specks against the bright edge of the sun.

Radios filled with overlapping voices. Commands. Warnings. Coordinates.

Sato pushed forward, throat dry, and tried to find one clear target, one clear job, one simple thing to do in a sky that had become too crowded for simple.

Below, the fleet cut through the water in sweeping turns. To a pilot, ships look slow even when they’re fast. Their wakes curl white behind them, elegant as calligraphy.

Then the air filled with noise and motion again. Sato saw flashes near the ships. He saw columns of smoke beginning to rise from somewhere in the formation. He saw aircraft diving, climbing, turning away, returning.

He did not see everything. No one ever does.

Later, he would remember only fragments: the glare of the sun; the sudden burst of black puffs in the air; the way his own hands gripped the controls so tightly his knuckles ached.

On the American side, the strike succeeded—but success came with a cruel bill.

Because as the pilots turned back toward their carriers, the sun was falling quickly, and the distance was long, and fuel gauges do not negotiate with courage.

The third day—if you can call it a day—was not about the enemy as much as it was about getting home.

Navarro’s shift blurred into the late evening. He heard voices on the radio that sounded calmer than they had any right to. He listened to controllers guiding returning aircraft over open water, counting them, adjusting patterns, making space.

On deck, lanterns appeared—more lights than doctrine preferred, more visibility than anyone liked. But doctrine doesn’t catch aircraft in the dark.

The carriers turned into the wind. The recovery cycle began.

Planes appeared as shapes at first, then as roaring, trembling machines with tired men inside.

Some came in too fast, too high. Some came in low and shaky. Deck crews ran, guided, signaled, grabbed. Lines snapped into place. Arresting cables did their hard work.

Every landing was a question: Will this one make it?

Navarro stepped out briefly and looked toward the flight deck from a passageway. He saw a landing that bounced once, twice, then caught a wire. He saw crew rush in. He saw a pilot climb out and just stand there for a moment, head bowed, as if realizing only now that he had been holding his breath for an hour.

And then, out of the darkness, another aircraft came in—its engine uneven, its approach too low. The deck officer’s signals grew sharper, urgent. The plane dipped, rose, dipped again.

It caught the wire, hard, and stopped. A collective exhale moved across the deck like wind.

Navarro felt something in his chest loosen. He hadn’t even known it was tight.

Not every aircraft returned. The carriers’ decks could not fill every empty space. But the fact that so many did return—at that hour, at that distance—felt like a kind of defiance.

On the Japanese side, there was no triumphant return. There was only the quiet accounting of what had been spent and what could not be replaced quickly.

Sato landed near midnight, exhausted and angry at his own exhaustion. When he climbed out, his legs trembled slightly, and he hated that too.

He walked past a line of aircraft parked too neatly, as if order could disguise loss. He saw mechanics sitting on the deck with their backs against equipment, staring at nothing. He saw an officer standing alone, hands clasped behind his back, looking toward the sea as if waiting for someone who would not come.

Sato found a quiet spot near the island structure and took out his notebook.

He stared at the page.

Then, finally, he wrote a single line:

The sky is wide enough for all our dreams, and still it has no room for our mistakes.

He closed the notebook and held it against his chest for a moment, like a shield that couldn’t stop anything but could at least remind him he was still himself.

By morning, the shape of the outcome was undeniable.

The Japanese carrier air groups had been worn down to a shadow. The American carriers still moved with power, still launched and recovered in disciplined rhythm. The sea remained calm, indifferent to which side now carried the advantage.

In the quiet after the busiest hours, the battle earned the kind of nickname men give things when they’re trying to make history fit into a phrase. But inside the seventy-two hours, it had not felt like a nickname. It had felt like work, and fear, and watching your fuel needle and the fading light with the seriousness of prayer.

Navarro returned to his radar set and watched the scope sweep, sweep, sweep. The ocean was still out there. The sky was still out there. Blips would still appear, and someone would still have to call them.

He realized that victory—real victory—didn’t always arrive as cheering. Sometimes it arrived as a quieter, heavier understanding: that something fundamental had shifted, and the rest of the war would follow that shift like a wake behind a ship.

Sato stood on his carrier’s deck and watched the horizon. He didn’t know what the next months would bring. He only knew that the air felt different now—thinner, harsher. As if the sky itself had taken note.

The sea stayed calm enough to forgive anything.

But it did not forget.

And in those seventy-two hours, with blips on screens and aircraft rising into sunlit air and landing in the dark, Japan’s carrier dream had been bent—hard—toward a future it could no longer fully control.

History would write it in dates.

The men who lived it would remember it in moments:

A faint mark on a radar screen.

A deck officer’s urgent hand signals in fading light.

A fuel gauge trembling near empty.

And the ocean—always the ocean—quietly holding everything that never came back.