How One Sniper’s “STUPID” Mirror Trick Made Him 5 TIMES More Deadly Than German Snipers

The fog was a liar. At 6:47 a.m. on November the 3rd, 1944, that fog was clinging to the ruins of Mets, France. It was a cold, wet shroud, promising concealment, promising safety. And crouched inside a pulverized bakery, Private First Class Michael Donovan was praying for it to stay. He was 22 years old.

He’d been in combat for 6 months, and through a jagged crack in the bakery’s wall, he watched the world emerge in shades of gray. Across the street, the German positions were ghosts, slowly taking solid form as the sun began its weak ascent. Donovan was a sniper. His job, on paper, was simple. Find the enemy snipers and kill them before they killed the men of the fifth infantry division.

The reality was suicide. The problem wasn’t the city. Mets was a fortress. Yes. Over 200 fortified positions, machine gun nests, and interlocking fields of fire. But the real problem, the lethal problem was the German marksman. They were different. They were invisible. They were patient. And they were hunting him.

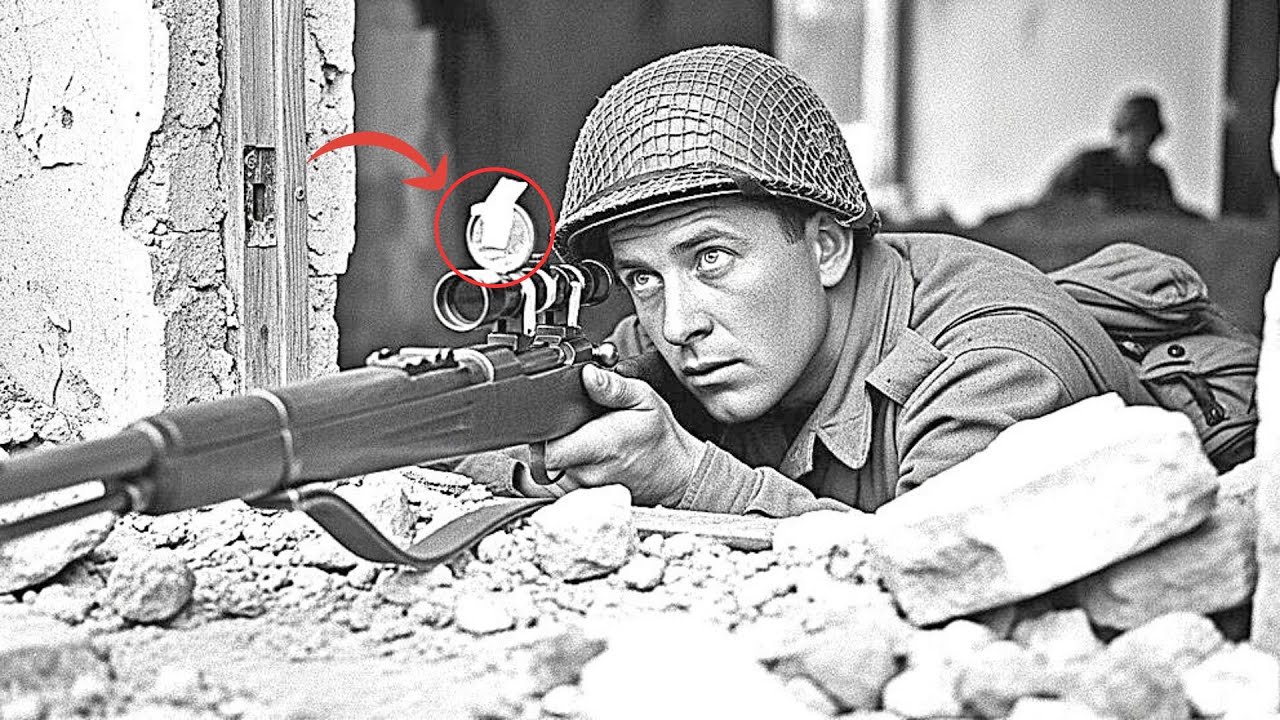

Donovan was not an amateur. He’d graduated at the top of his sniper class at Fort Benning. He was armed with the legendary M1903 Springfield, a rifle accurate to 800 yd, topped with a scope that could bring the enemy’s face right to him. But none of it mattered because the Germans saw him first every single time without exception.

By early November, the Fifth Infantry Division had lost 23 American snipers in the fight for Mets. Think about that number. 23 not infantrymen running into a machine gun. 23 snipers, the elite, the best marksmen in their battalions. The hunters had become the hunted. 23 empty bunks. 23 letters home that started with, “We regret to inform you.

” 23 men [clears throat] erased and they were all killed the exact same way. Shot while searching for a target. They never even saw. Donovan had tried to solve the puzzle. He’d interviewed the spotters, the medics, the men who survived. The pattern was always the same, a single perfect shot.

From an angle, no one was watching. The Germans had perfected a doctrine called the doppel stell. The double position. It was lethally simple. A German sniper team would prepare two concealed positions 30, 50, sometimes 100 yards apart. They would fire a single shot from position A. The moment that rifle cracked, the American sniper team would dive for cover and then do exactly what they were trained to do.

Scan the area of the muzzle flash. Triangulate the shot. Find the enemy. It took time. 12 seconds. 15, maybe 20. Time to settle the scope, breathe, search the rubble, find the glint of steel. But it was a trap because the German sniper was already gone. He’d fired and immediately moved, crawling through a trench, a tunnel, or a sewer to position B. And from position B.

He wasn’t hiding. He was waiting. He was aiming. right at the spot where the American snipers had to be. By the time Donovan or his partners had their scopes trained on position A, the German was already pulling the trigger from position B. The math was simple. It was brutal and it was perfect. The Americans were searching. The Germans were aiming.

The Germans shot first. Always. Donovan’s first partner had been Corporal James Bradley. October 18th, 1944. Bradley was a farm kid from Nebraska. The kind of quiet, steady hand who, as the stories went, could hit a running rabbit at 200 yd. In 3 weeks, he’d already racked up nine confirmed kills. He was good. He was fast.

That morning, they were set up in a collapsed textile mill. Bradley was on the scope, scanning a factory building 400 yd distant. Donovan was spotting, watching the flanks. There was no sound, no warning, just the snap of a bullet breaking the sound barrier, followed a half second later by the thack of impact and the distant crack of the rifle.

A 7.92 mm Mouser round. It hit Bradley high on the head. He was dead before his body hit the floor. He’d been scanning the front when the shot came from a side window 400 yd away. Donovan never saw the muzzle flash. He never saw the German. He fired three rounds at the window. Suppression fire. Pure instinct.

But he knew the man who had been eating rations with him 10 minutes earlier was gone. The enemy sniper had spotted them, aimed, fired, and likely vanished before Donovan even knew they were being hunted. Bradley died instantly. Donovan had to carry his body back at dusk. Command sent a replacement. The line had to be held.

The mission continued. His second partner was Private First Class Robert Chen. October 29th, just 11 days after Bradley. Chen was different. Not a farm boy. He was from San Francisco. Sharp eyes, steady hands, a bit of city swagger, 12 confirmed kills. He was an artist with the Springfield. They’d been working together for 8 days.

8 days of whispered conversations. 8 days of sharing stale bread. 8 days of watching each other’s backs. They were in a new sector. Rubble near a trench line. Chen was on the scope. Donovan was spotting the samesequence. The snap, the thwack, but this one was different. Chen wasn’t killed instantly. The round hit him in the chest. It punched through his lung.

He looked at Donovan. Confused. He tried to speak and then he started to gasp. A horrible wet sound. Donovan scrambled to him, ripping open Chen’s field dressing. He pushed the bandage against the wound, but the blood was bubbling from it. Chen was drowning, drowning in his own blood on a dusty floor in France.

Donovan screamed for a medic. He kept pressing. He told Chen to hold on. He told him he’d be okay. Chen’s eyes were open. He was conscious and he was terrified. He lived for 40 minutes. 40 minutes. Donovan held him, pressing on the wound, screaming for help that was pinned down by machine gun fire, watching his partner, his friend, suffocate.

The German sniper had been concealed in a pile of rubble 350 yards away. After Chen died, after the medics finally arrived and pronounced him dead, after Donovan was left alone again, he found the Germans position. It was a perfect hide, a small hole in a mountain of bricks. The German was long gone. He’d probably been watching them for an hour. The pattern was unbreakable.

American sniper sets up. American sniper searches. German sniper, already watching, fires first. American sniper dies. Command kept issuing the same useless orders. Stay mobile. Change positions frequently. Use concealment. They didn’t understand. They couldn’t see the problem. Donovan saw it.

He saw it in the back of his eyelids every time he tried to sleep. Bradley falling like a marionette with cut strings. Chen, his eyes wide, gasping. He spent the next three nights not sleeping, but thinking he’d sit in the dark, his rifle cold in his hands, and stare at the scope. The scope was the problem. When you looked through an 8x magnification scope, your entire world shrank. It shrank to a tiny 8° cone.

It was like looking at the war through a toilet paper tube. You could see a single window frame 400 yd away with perfect clarity. But you couldn’t see the other window 50 ft to its left. You couldn’t see the rooftop above you. You couldn’t see the pile of rubble behind you. Everything outside that narrow cone was invisible.

And the Germans knew it. They didn’t attack the cone. They attacked the man holding it. They exploited this blindness ruthlessly. They didn’t shoot from the positions the Americans were watching. They shot from the flanks. They shot from angles the Americans weren’t scanning. By the time an American sniper, frustrated, turned his scope to search a new sector.

A German sniper was already aimed at his head, waiting for the movement. How do you defeat an enemy who sees you when you can’t see him? How do you watch your front and your back at the same time? How do you see the threats you aren’t looking for? Donovan was now alone. He was a sniper without a spotter.

Command told him to wait, that a new partner was being transferred. Donovan knew he was just being assigned a new man to watch die. He was number 24 on the list. He just didn’t know the date. On the third night after Chen’s death, Donovan was cleaning his kit, not his rifle that was already immaculate, his personal kit.

He pulled out his standardisssue shaving bag. He opened it. A bar of soap, a worn out razor, and a simple 4×6 in mirror. Standard military issue metal frame. He picked it up, stared at his own reflection. exhausted, 22 years old, looking 40, he looked from the mirror to his rifle, laying on his cot, from the rifle, back to the mirror, and then an idea, an insane idea, a desperate, hopeless, brilliant idea.

What if he could use the mirror to see behind him while he was still looking forward? It was insane. It was completely, utterly against every regulation in the book. Modifying precision sniper equipment without approval from ordinance, altering your issued gear, that’s how you got court marshaled. But Bradley was dead.

Chen was dead. 23 American snipers were dead. Donovan didn’t want to be number 24. He worked alone on the night of November 2nd. His unit was holed up in what had once been a hotel. Now it was just a skeleton of shattered walls, collapsed ceilings, and broken glass. The air was thick with the smell of smoke, cordite, and damp plaster.

He found a quiet corner on the third floor, a room where the roof was mostly intact. He lit a single dim flashlight. The November night was cold. He could see his own breath fogging in the beam. From his pack, he pulled the mirror. 4×6 in metal frame, scratched but reflective. He also pulled out a roll of electrical tape salvaged from a signal core wire spool, a knife, wire cutters.

These were not precision tools. They were the tools of a desperate man. He set his M1903 Springfield on a makeshift table of broken furniture. The ATNX scope sat 3 in above the barrel, held by steel rings. The mirror had to be mounted where he could see it while his eye was pressed to the scope, but it couldn’tinterfere with the rifle’s operation.

It couldn’t block his sight picture, he tested positions. Too high, and he had to lift his eye from the scope. A fatal mistake. Too low and it blocked his view of the rifle’s bolt. Too far forward, and the angle was useless. After 20 minutes of silent trial and error, his hands numb from the cold, he found it, the perfect position, mounted on the left side of the scope, angled at 45°, positioned about 8 in forward of his eye.

From there, when he looked through the scope, he could see the mirror in his left eye’s peripheral vision. a tiny flickering image. A glance, just a fractional shift of his eye, not his head, and he could see his flank. He could see behind him. His hands were shaking as he began the installation. Not from the cold, from the sheer terrible gravity of what he was doing.

This violated everything he’d been taught. Unauthorized modifications to precision equipment, altering military property. The minimum punishment was reassignment to a rifle platoon, a death sentence. The maximum was a dishonorable discharge. But Chen’s face kept appearing in the dim light. Chen gasping for air, blood bubbling from his chest, dying slowly while Donovan watched.

Chen had been looking forward. The German shot him from the side. If Chen had been able to see that flanking angle, he might still be alive. Donovan cut the electrical tape into strips. He wrapped them around the mirror frame to create a cushion, then wrapped more tape around the thickest part of the scope tube.

The tape was for padding, for grip. The mirror had to stay in place during the rifle’s brutal recoil. It couldn’t shift. It couldn’t rattle. The installation took 40 agonizing minutes. His frozen fingers kept slipping on the tape’s adhesive. The mirror kept sliding out of alignment. Twice it fell off completely, clattering against the broken floor.

Each time it fell, his heart pounded in his chest. If anyone heard him, if an officer came to investigate, he’d be in irons before morning. Finally, it held. He shouldered the rifle, pressed his eye to the scope, aimed at a dark stain on the far wall, glanced left. The mirror showed him the doorway, the hallway behind him, his entire rear arc. It worked.

He ran the tape around the mirror frame three more times, securing it tight, making it solid. He tested the rifle’s balance. The mirror added maybe 4 oz. Negligible. He checked the scope’s alignment. Still perfect. The modification looked crude. It looked like something a child would make. Obviously, not factory equipment.

Any officer who inspected the rifle would see it instantly. But Donovan didn’t plan on letting any officers inspect his rifle. He cleaned up the tape scraps, put away his tools. It was 045. In 5 hours, he’d be moving to a new position in the destroyed industrial district. German snipers owned that sector.

Three American snipers had died there just in the past week. Tomorrow, Donovan would find out if a simple shaving mirror could change the math of death. That morning, he met his new partner, Private Sam Martinez, 19 years old, from Texas. He’d been a sniper for 3 weeks. Zero kills, good instincts, scared. As they moved out in the pre-dawn gray, Martinez saw the contraption on Donovan’s rifle.

He pointed, “What is that?” Donovan looked at him. Survival. Martinez didn’t ask any more questions. At 0647, they were in position. The same destroyed bakery Donovan had been in days earlier. The south wall was gone, exposing them to the street. But the bakery’s old brick oven provided a solid, dark fortress within the ruin.

A crack in the wall gave them a narrow view of the German-h held factory complex. 400 yd away. perfect sniper terrain. Martinez covered the room’s entrance, his M1 Garand at the ready, watching for German infantry. Donovan settled behind his Springfield. The morning fog was lifting. The factory emerged from the gray.

Broken windows, collapsed roofs, piles of rubble. Somewhere in that wreckage, they were waiting. Donovan pressed his eye to the scope. The 8x magnification brought the factory into sharp, terrible focus. He began his scan left to right, slow, methodical, looking for a shadow that was too dark, looking for movement, looking for the tiny circular glint of an enemy scope.

His field of view was narrow, a 50-ft cone 400 yd away. That’s what killed Bradley and Chen. They’d been looking through this same narrow tube, blind to the world. But now Donovan had the mirror. In his left eyes’s peripheral vision, it was there, a small, scratched, distorted reflection. It showed the street behind him, the ruined buildings across the way, his flanks.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was something. At 0723, he saw it. Movement. Factory. Third floor. Damaged window. A shadow. Could be debris. Could be the wind. He held his aim steady, breathed. The movement came again. Human. Definitely human. A German soldier moving slow. Careful. A sniper setting up. Donovan calculated thedistance. 410 yd. No wind. An easy shot.

His finger tightened on the trigger. He was about to end it. And then he saw it in the mirror. A flicker. A tiny, almost imperceptible shift of light behind him. Across the street, a building he’d thought was empty. Third floor window. Donovan did not move. He did not turn his head.

He kept his eye glued to the scope, his rifle aimed at the factory, but his attention, his entire world, snapped to the mirror. He watched the reflection, and there he saw it. the glint of a scope, the dark line of a rifle barrel, a German sniper. The German was aiming directly at him, at the crack in the wall. He’d probably been watching them for minutes.

He was probably right now taking his last breath before pulling the trigger. This was it. This was the exact moment. The moment Bradley died. The moment Chen died, focused on a target to the front while a flanking sniper prepared the kill shot, but Donovan saw him, the mirror worked. He kept his rifle locked on the factory and whispered, his voice barely a breath.

Martinez, German sniper, building behind us, third floor, left window. He’s aiming at us right now. Martinez, to his credit, didn’t flinch. He just moved slow, [snorts] smooth. He brought his M1 Garand up, aimed toward the building behind them, found the window, Martinez whispered. I see him, Donovan said.

On my count, I take the one in the factory. You take the one behind us. 3 2 1 fire. The Springfield cracked. The recoil slammed into Donovan’s shoulder. 410 yd. The German in the factory window jerked backward, hit center mass. He fell out of view. The instant Donovan fired, Martinez fired. The Garan’s 306 round punched through the window frame behind them.

The German sniper, the one who had been seconds from killing them, slumped forward, his rifle falling from the window. Two shots. Two kills. 5 seconds. Donovan worked the Springfield’s bolt, ejected the hot, spent casing, loaded a new round, scanned through the scope again. The mirror showed no more threats. They were clear.

Martinez was breathing hard, the adrenaline pumping. He stared at Donovan. That the German was about to shoot you. He had you dead. How? How did you see him? Donovan just tapped the crude tapecovered mirror on his scope. Martinez stared at it for a long, long moment. You need to put that on every sniper rifle in this battalion.

The engagement that morning lasted 4 hours. Donovan’s team eliminated six German snipers. Donovan got four. Martinez got two. And the mirror saved their lives three more times. Three times, Donovan spotted a target through his scope, only to see a second threat, a flanking threat, appear in the mirror. Each time, the coordination worked flawlessly.

Martinez engaged the flanking threat. Donovan took the forward target. The German double position tactic was useless. Their unbeatable system was broken. It was broken by a 10-cent piece of glass and some tape. By afternoon, word had spread. Donovan’s team had six kills and zero casualties. Other teams wanted to know how.

Martinez told them about the mirror. By evening, three more snipers from the platoon wanted the modification. The first was Sergeant Frank Wilson, 28 years old, from Montana, a hunter. He had lost two partners in 3 weeks, both killed by flanking shots they never saw coming. Wilson watched Donovan install the mirror on his rifle that night in the same dark ruined hotel room.

He asked questions about the angle, the position. When Donovan finished, Wilson tested it, looked through the scope, glanced at the mirror. He looked at Donovan and said, “It’s perfect. I should have thought of it.” The next morning, Wilson’s team engaged German snipers near the cathedral. Wilson spotted two using the mirror.

He eliminated them both before they could fire. He came back that night raving. The modification, he said, had saved his life. He told every sniper he knew. By November 8th, Donovan had installed mirrors on nine rifles. The modification spread, sniper to sniper, team to team. They stopped waiting for Donovan. Snipers started making their own mirrors using whatever they could find.

Broken glass, polished belt buckles, even pieces of chrome ripped from destroyed vehicles. The battalion’s kill ratio Santa began to shift. In October, American snipers in Mets lost two men for every one German eliminated. A 1:2 ratio, a losing game. By mid- November, the ratio was 4:1 in American favor. Four German snipers killed.

For every American lost, the hunters were back. But now, Donovan had a new problem. The modification was no longer a secret. It was popular. And on November 10th, the man in charge came to find out why. Captain Robert Hayes commanded the battalion sniper platoon. He was career army 12 years in service. He knew every sniper manual by heart.

He was a man who went by the book. He was doing a standard inspection, checking equipment, verifying rifle zeros. He climbed the stairs to Donovan’s position in a bombedout church tower. He saw Donovan. He saw Martinez. And he saw the mirror taped to Donovan Springfield. Hayes just stopped. He stared at it.

For a long, silent 10 seconds, he pointed. What is that, private? Donovan’s stomach dropped. This was it. The court marshal. Everything he had feared. Before Donovan could even think of an answer. Martinez spoke up. It’s a mirror, sir. A modification. Martinez explained everything. He talked about Bradley. He talked about Chen.

He talked about the German flanking tactics. He explained how the mirror let them see those threats. He told Hayes it had saved their lives multiple times. He finished with, “It’s completely unauthorized, sir, but it works.” Hayes looked at Martinez. Then he looked at Donovan. He walked over. He didn’t yell. He just looked at the rifle.

He examined the crude tape. He tested the angle of the mirror. He bent down, put his eye to Donovan’s scope. He glanced at the mirror. He stood up. He understood. Instantly, he looked at Donovan. His voice was quiet. How many rifles have this modification? Donovan’s throat was dry. Nine, sir, including mine. Hayes was silent for another long moment.

Donovan prepared to be arrested. Then Hayes said something Donovan never expected. By tomorrow morning, I want every sniper rifle in this battalion to have one. That’s an order, private. He looked at Donovan. I’ll handle the paperwork. You You just focus on keeping my men alive. Donovan stood there stunned.

Hayes, a man who lived by the book, had just ordered him to rewrite it. He had just made an unauthorized court marshalworthy field modification. official battalion policy. Hayes understood. He understood that regulations were ink on paper, but his men were blood and bone. He was willing to risk his career to save his snipers. That night, Donovan didn’t sleep.

He didn’t just work, he led. He recruited Wilson, Martinez, and the other snipers who had the modification. He showed them how to install the mirrors, the exact angle, the best positioning, the right way to tape it so the recoil wouldn’t shatter it. They worked all night in the basement and ruined buildings of Mets.

A small secret factory of desperate men. Some mirrors were mounted with tape. Others used salvaged telephone wire. One sniper, a farm boy from Iowa, used leather straps he cut from a German gas mask case. The methods varied. The principle was the same. Give the hunter 360° vision. By the morning of November 12th, every sniper in the battalion had a mirror on his rifle, and the German snipers walked into a buzzsaw.

Their world changed overnight. Their unbeatable doppelstelling tactic. San Farik now got them killed. They would set up their two positions. They’d fire from position A, expecting the Americans to foolishly scan that spot. But the American sniper wasn’t scanning position A. He was already watching position B in his mirror.

Again and again, German snipers moving to their second position would be met by a single 306 round from an American sniper they thought they were outsmarting. Intelligence reports captured later showed the confusion. German commanders in Mets wrote about the unusual and aggressive new American sniper tactics. They reported that Americans were engaging flanking positions they shouldn’t have been able to see, that they were counterattacking before the German snipers could even fire their second shot.

The Germans tried to adapt. They moved further back trying to engage from 600 800 yd. It didn’t matter. The mirror showed movement regardless of distance. They tried attacking with multiple snipers at once, hoping to overwhelm the Americans. It didn’t work. The American teams working in pairs were now invulnerable.

One man on the scope watching forward. One man, Martinez, watching the mirror. Nothing got past them. By late November, the unthinkable happened. The German snipers, the terror of Mets, stopped engaging. They started avoiding the American sniper teams. The tactical advantage hadn’t just shifted. It had been conquered.

The modification, of course, never became officially sanctioned by the army during the war. Not really. A training inspector noticed the crude mirrors in December 1944. He wrote a scathing report. unauthorized modifications, violation of ordinance protocol, lack of standardization. The report circulated for weeks. Officers in the rear debated how to handle it.

On one hand, it was a complete breach of regulations. On the other, the sniper teams using these mirrors had survival rates and kill ratios that were unprecedented. In January 1945, an official evaluation team from Aberdine proving ground came to Mets. Three officers, two civilian ballistics experts. They inspected the mirrors. They tested them.

They interviewed the snipers. They measured the field of view improvement. They calculated the tactical advantage. Their conclusion, the mirrors, were a significant survivability enhancement. They needed to be integrated into sniperdoctrine immediately. The team went back to the states and wrote a formal recommendation.

They suggested that all sniper rifles be fitted with peripheral mirrors. They even designed standardized mounting brackets. They made it sound like they had discovered the innovation. Private first class Michael Donovan’s name never appeared in the documentation. Neither did Martinez’s. Neither did Hazes.

The official record would show that Army evaluators had identified a problem and developed a solution. Captain Hayes was furious. He tried to correct the record. He wrote letters. He submitted afteraction reports, making sure Donovan’s name was in every single document from his battalion. But those reports got lost, filed away, buried in the massive bureaucracy of a global war.

The evaluation team’s version became the official one. Donovan learned about this in February 1945. An officer showed him the paperwork, asked if he wanted to file a complaint. Donovan read it. He saw his idea, his desperate middle of the night gamble. credited to a committee. He just handed the paper back and said no.

He didn’t care about the credit. He cared that snipers were surviving. That partners weren’t dying from shots they never saw coming. The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. Donovan had survived 11 months of combat, 47 confirmed kills. The mirror had saved his life. At least six more times. Martinez survived 14 kills. After the war, he went back to Texas, became a police officer.

For 30 years, he kept a photograph of Donovan’s rifle on his desk. Wilson survived. 31 kills. The mirror saved him four times. He went back to Montana, became a hunting guide. Donovan stayed in the army until 1946. Then he went home to Pennsylvania. He got a job in a factory, the same work he’d done before the war. He married in 1947.

He had three children. He lived quietly. He never talked about the war. When people asked, he’d just say, “I was a sniper, that’s all.” He didn’t mention the mirror. He didn’t mention saving dozens of snipers. He didn’t mention changing the face of sniper warfare in Europe. It wasn’t modesty. He just didn’t think it mattered anymore.

By the 1960s, the mirror modification had been forgotten. New [clears throat] scopes had better optics. The official Army history of sniper operations never mentioned Donovan. His contribution had been erased. Not by malice, just by time, by bureaucracy. Field modifications aren’t historically significant.

Official developments are, and that is where the story should have ended. But it didn’t. In 1987, a military historian researching sniper innovations found references, unusual references. In 1944, maintenance logs from the fifth division. Mentions of improvised mirrors. The logs mentioned a private first class Donovan. The historian spent months tracking down veterans from that unit.

He found Sam Martinez and Martinez told him everything about Bradley, about Chen’s horrific death, about Donovan installing the mirror in the dark, about how it spread, about how it saved them. The historian found Donovan. He was 67 years old, still in Pennsylvania. The historian asked him, “Did you install these mirrors?” Donovan said, “Yes.

” The historian asked, “Why? Why?” He’d never talked about it. Then he told Donovan, “Based on survival rate improvements, that simple 4×6 mirror had likely saved between 40 and 60 American sniper lives.” Donovan was quiet for a long time. And then he said, “I never counted. I just I just remembered Martinez and Wilson and the others who came back.

” Michael Donovan died on June 7th, 2001. He was 79 years old. His obituary mentioned his service in World War II. It did not mention the mirror. It did not mention that he saved dozens of lives. His funeral was small. Family, a few friends, and four old men his family didn’t recognize. After the service, they introduced themselves. They were snipers.

Men whose lives had been saved by the mirror. They’d read about Donovan’s death in veterans newsletters and had driven hundreds of miles to pay their respects to make sure his family knew. Today, Donovan’s story exists in fragments, in old logs, in transcripts. But if you visit the Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, you can see an M19903 Springfield from World War II.

And mounted on the scope is a small rectangular mirror for 6 in metal frame held on by crude tape. It’s labeled field modification common in late 1944. No name attached. That mirror is Donovan’s legacy. Not the official one, the real one. That’s how innovation actually happens in war. Not in committees, but in the dark by soldiers who see a problem, who risk everything because their friends are dying and they can’t stand to watch it anymore.

He installed the mirror to save one man. His idea saved dozens and nobody remembers his name. But now you