How America Built “Massive Floating Shipyards” Repairing Ships Every 48 Hours at Sea DT

November 17th, 1944. Ulyy Atal, Western Caroline Islands. Commander Richard Hayes stands at the edge of what appears to be a harbor that shouldn’t exist. The lagoon before him stretches 15 miles across, a natural anchorage so vast it could hold the entire United States Pacific Fleet. And today it does. six Essexclass carriers, four battleships of the Iowa and South Dakota classes, 23 cruisers, 67 destroyers, nearly 400 ships in total, the largest concentration of naval power ever assembled. But that’s not what stops

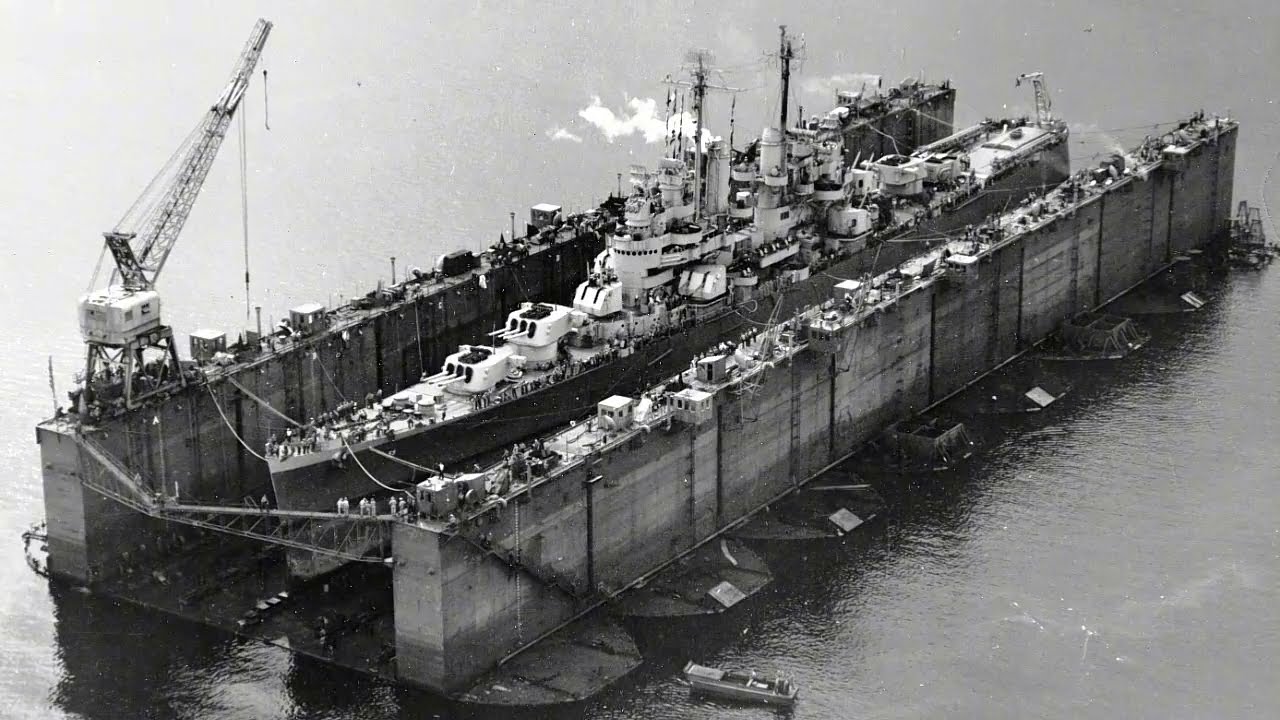

Hayes in his tracks. It’s the structure floating in the center of the lagoon that defies belief. 10 massive steel sections, each 100 ft long and 78 feet wide, connected end to end to form a single monolithic dock. The walls tower 90 ft above the water line. Inside this floating canyon sits the battleship USS North Carolina.

All 35,000 tons of her lifted completely out of the water as if by some biblical miracle. Her hall, normally hidden beneath the Pacific, is exposed to the tropical sun crawling with hundreds of workers in Navy dungarees and CB hats. The sound of riveting guns, welding torches, and grinding metal echoes across the lagoon like industrial thunder.

Hayes [snorts] has been in the Navy for 22 years. He watched the Brooklyn Navyyard rebuild the USS Arizona after World War I. He knows what ship repair looks like. Ship repair happens in Brooklyn, in Pearl Harbor, in San Francisco. Ship repair does not happen 7,000 m from the nearest major port in a lagoon that 6 months ago was held by the Japanese, serviced by a dock that arrived here in pieces aboard cargo ships. This cannot be real.

No navy can bring the shipyard to the war. But standing before him is the proof that American industrial might has accomplished exactly that. Advanced base sectional dock number one, ABSD1. The sailors call it the mighty A. The Japanese have no idea it exists. The North Carolina took a torpedo hit off truck 3 weeks ago.

The blast tore a hole in her hole 40 ft wide. By every calculation of distance and damage, she should be steaming back to Pearl Harbor right now. A journey of 3,000 miles that would take her out of action until February. Instead, she will return to combat operations in 8 days. This is not supposed to be possible. The Japanese naval strategy depends on it being impossible.

They calculated that American ships damaged this far from home ports would require months to return to action, giving Japan time to rebuild strength, to fortify positions, to prepare defenses. The entire War of attrition strategy depends on geography being Japan’s ally, on the vast Pacific distances keeping American ships away long enough to matter.

What they never counted on was America building shipyards that could cross oceans. This reality changed everything. If you want to see how this innovation rewrote the strategic landscape of the Pacific, support us with a like. It helps us uncover more buried stories like this. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Now back to how this impossible feat began.

The journey to this moment began not with naval architects or combat admirals, but with a single bureaucrat in Washington who understood a simple truth. You cannot win a war 7,000 mi from home if every damaged ship must sail 7,000 mi to be repaired. The solution that would transform Ulithy into an industrial fortress took shape four years earlier in the desperate months after Pearl Harbor when the full scope of the Pacific challenge became clear. February 15th, 1942.

Bureau of Yards and Docks, Navy Department, Washington DC. Commodore Andrew Carl Olsen stares at a map of the Pacific and confronts a mathematical nightmare. The United States is now at war with Japan across an ocean that spans 9,600 m from San Francisco to Tokyo. The nearest major American shipyard to the combat zone is Pearl Harbor itself, 3,800 m from the forward operating areas.

Beyond Pearl, there is nothing. No ports, no facilities, no way to repair battle damage short of a round trip that could take 3 months. Olsen is not a combat officer. He is a civil engineer, a builder of docks and harbors, a man who thinks in tons of concrete and cubic yards of steel. But he understands that logistics, not battleships, will determine who wins this war.

Japan has interior lines of communication, ports throughout the Pacific, repair facilities at Rabal, Truck, and across the South Pacific. America has Pearl Harbor and San Francisco separated by an ocean that swallows damaged ships for months at a time. The Navy already operates small auxiliary repair docks, ARDs, capable of lifting destroyers and smaller vessels.

ARD1 through ARD12 are already being constructed or deployed. But these docks can handle ships displacing only 3,500 tons, a destroyer, perhaps a small cruiser. They cannot touch a battleship, a fleet carrier, or a heavy cruiser. The capital ships that will decide the Pacific War. Olsen proposes something unprecedented. A massive floating dry dock that can bebuilt in sections, transported across the Pacific aboard cargo ships and assembled at forward anchorages.

Not a permanent installation requiring years of concrete and dredging, but a mobile industrial facility that can lift a 45,000 ton battleship out of the water in the middle of nowhere. The skeptics in the Bureau of Ships think it’s madness. The engineering challenges alone seem insurmountable. Each section must be watertight, capable of withstanding Pacific storms during the trans oceanic tow.

The sections must connect with perfect alignment, maintaining structural integrity while supporting tens of thousands of tons. The pumping systems must be powerful enough to ballast and debalast the entire structure in hours, not days. And it must be designed to operate with minimal shore support, staffed by naval construction battalions in tropical anchorages with no infrastructure.

But Olsen has done his calculations. A single ABSD properly positioned could repair dozens of ships that would otherwise require monthsl long voyages to Pearl Harbor or the West Coast. It would effectively double the combat availability of the fleet. The cost in steel and construction resources would be enormous but far less than the cost of building replacement ships for those lost because damaged vessels couldn’t return to battle.

On March 8th, 1942, the Navy Department approves construction of the first advanced base sectional dock. The initial ABSD1 design called for 10 sections, each measuring 93 ft long, 78 ft wide, and capable of being ballasted to 60 ft below the water line. When connected, the sections would form a 930 foot long floating dry dock with a clear width of 240 ft inside the wing walls, large enough to accommodate an Iowa class battleship.

The lift capacity would exceed 90,000 tons. Construction began at Advanced Marine Steel Corporation in Oakland, California in June 1942. Each section was essentially a massive floating steel box with ballast tanks, pumping systems, and structural frames designed to support incredible compressive loads. The walls incorporated ladders, workshops, power distribution systems, and living spaces for the operating crew.

Each section could function independently for the Trans-Pacific Voyage, then mate with its neighbors through massive locking pins and rubber gasket seals. The first complete ABSD1 departed California in sections aboard a convoy of cargo ships in August 1943 bound for Espirit Tusanto in the new Hebdes.

The voyage took 31 days. Upon arrival, Navy Construction Battalion crews CBS spent 3 weeks assembling the sections into a functional dry dock. On October 12th, 1943, ABSD1 lifted its first ship, the destroyer USS Case, damaged by a Japanese torpedo off Kolangara. The case had taken a hit that tore open her forward engine room.

Under normal circumstances, she would have faced a 3-month journey back to Pearl Harbor. Instead, CB ship fitters and Navy machinists repaired the damage in 17 days. The destroyer returned to active patrol on October 29th, 1943. The experiment had worked. The floating factory was operational through late 1943 and into 1944.

The pattern repeated across the South Pacific as additional docks arrived and began operations. ABSD2 entered service at Manis Island in the Admiral T Islands in March 1944. The massive Sea Adler Harbor Anchorage became the forward repair base for the Seventh Fleet. Within its first month of operation, ABSD2 handled 14 ships, three destroyers with torpedo damage, two cruisers with shell hits, and nine vessels requiring routine bottom maintenance that would normally require a return to Pearl Harbor.

ABSD3 deployed to Espirit Tusan Sananto, joining ABSD1 in creating redundant repair capacity. Between the two docks, the South Pacific repair facility could now handle two capital ships simultaneously or four destroyers or any combination in between. The smaller ARDs spread across the forward areas like industrial seeds taking root.

ARD10 operated at Mil Bay, New Guinea. ARD8 served at Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. ARD11 positioned at Numea, New Calonia. Each location became a node in a vast repair network that stretched across 5,000 mi of ocean. The impact on fleet operations was immediate and dramatic. Ships that suffered combat damage no longer faced automatic retirement from the forward areas.

A damaged cruiser could be back in action in weeks instead of months. A destroyer with a hole in her side could return to escort duty in days. The Navy’s combat power in the forward areas stopped bleeding away through the slow hemorrhage of damaged ships limping back to Pearl’s Harbor. From the Japanese perspective, something impossible was happening.

American ships that should have been removed from the battle were reappearing with inexplicable speed. When the cruiser USS Denver took a torpedo hit during the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on November 2, 1943, Japanese naval intelligence marked her as effectively lost, out of action forat least 6 months. The Denver entered ABSD1 at Espiritus Santo on November 12th.

She returned to combat operations on December 8, just 36 days after taking the hit. The Japanese began to notice the pattern, but they couldn’t explain it. Post-war interrogations of Japanese naval officers revealed that they assumed the Americans had somehow built a major shipyard at Pearl Harbor with capabilities approaching those of West Coast facilities.

The concept of mobile dry docks operating in forward anchorages simply didn’t register as possible. But the true gamecher was yet to come. By mid 1944, American forces had seized Ulithia Tallal in the western Caroline Islands. The massive natural harbor 15 mi wide and protected by a coral reef sat just 1300 m from the Philippines and 3,000 m from Tokyo.

It was perfectly positioned to support the final drives toward Japan. But it was also 3,800 m from Pearl Harbor and 6,400 m from San Francisco. Any ship damaged in the Philippine or Formosa operations would face a catastrophic journey home. The solution arrived in sections between October and December 1944.

ABSD1 freshly expanded to 12 sections making it the largest floating dry dock in the world. March 11th 1945 1925 hours. Ulithy Atal. The aircraft carrier USS Randolph hole number CV15 rides at anchor in the fleet anchorage. Her crew preparing for the evening meal. She has been operating continuously since February, launching air strikes against Japanese positions in the Bonan Islands.

Tomorrow she is scheduled to rejoin Task Force 58 for operations off Okinawa. The kamicazi appears without warning. A single engine Yokosuka P1Y Francis bomber flying at wavetop level in the gathering dusk. It clears the reef, pulls up sharply, and slams into the starboard side at the aft flight deck edge. The 550lb bomb it carries detonates on impact.

The explosion tears through the carrier’s afterflight deck, blowing a hole 30 ft wide. Metal fragments shred through the gallery deck below, killing 25 men and wounding 106 more. Aviation gasoline ignites, sending flames 50 ft into the air. The after elevator is jammed halfway between the hangar deck and flight deck, its hydraulics destroyed.

16 aircraft on the aft flight deck are destroyed or damaged beyond repair. For the kamicazi pilot and his commanders, it is a perfect strike. An Essexclass carrier, one of America’s most valuable assets, is crippled 3600 m from Pearl Harbor. The mathematics of distance dictate her fate. 3 weeks to steam to Hawaii, 2 months in dry dark for repairs, 3 weeks to return to the combat zone.

The Randolph will miss the entire Okinawa campaign. She is effectively removed from the war until summer. But the mathematics have changed. At 2015 hours, less than an hour after the attack, damage control teams have the fires under control. By 21 hours, the commanding officer, Captain Felix Baker, sends a message to Vice Admiral Mark Mitcher, commander of Task Force 58.

The message is brief. Ship heavily damaged but afloat. request permission to enter repair dock at Ulithy. On March 12th at 0830 hours, the moves slowly through Ulithy Lagoon under her own power, guided by harbor tugs toward the massive gray walls of ABSD1. The dock has been emptied in preparation, its ballast tanks pumped to raise it high in the water.

The carrier enters the dock’s cavernous center section, fitting with just 8 ft of clearance on each side. At 10:15 hours, the ballasting begins. Massive pumps force water into the dock’s wing wall tanks, carefully controlled to maintain level descent. The dock sinks beneath the carrier, settling 60 ft below the surface.

The Randolph, all 27,500 tons of her, gradually rises clear of the water as the dock’s internal cradle takes her weight. By 1430 hours, the Randolph sits completely exposed, her entire hull visible from keel to flight deck. The damage is worse than initially assessed. The bomb blast and subsequent fire have twisted structural frames, melted wiring, and compromised the starboard side hull plating.

In a traditional shipyard, this would require at least 2 months of work. CB welders and Navy ship fitters swarm over the carrier within minutes of the dock stabilizing. They work in three shifts, 24 hours a day. New steel plate arrives aboard supply ships. Replacement elevator components are transferred from depot ships anchored nearby.

Electrical cables are spliced and rerouted. Damaged structural frames are cut away and replaced. Commander Robert Larson, the repair officer overseeing the work, later described the scene. It looked like organized chaos. 200 men crawling over every damaged section, cutting, welding, grinding 24 hours a day. The noise was unbelievable, but every man knew what he was doing.

We had it down to a science by then. On March 25th, 14 days after entering ABSD1, the USS Randolph is refloated. On April 1st, she launches aircraft in support of the Okinawa invasion, exactly three weeks after the kamicazi strike that shouldhave removed her from the war until July. The Japanese naval staff simply could not comprehend what had happened.

A carrier clearly and heavily damaged had returned to combat operations in less than a month without leaving the forward operating area. How was this possible? Where was the shipyard? Where were the facilities? The answer was floating in the center of Ulithy Lagoon, and Japanese intelligence had completely missed it.

Postwar examination of Japanese naval intelligence reports reveals zero references to advanced base floating dry docks. They knew about Pearl Harbor’s existing graving docks. They tracked ship movements to and from the West Coast. They understood the tyranny of distance that governed the Pacific War. But they never discovered that America had eliminated distance from the equation by bringing the repair facilities to the battle zone.

The implications were staggering. Every ship the Japanese damaged but failed to sink could be returned to combat in weeks. Every torpedo hit, every bomb strike, every shell that crippled but didn’t destroy a vessel was no longer a strategic victory. The war of attrition that Japan had planned depended on cumulative damage reducing the American fleet’s effective strength.

Instead, the fleet maintained near constant strength despite continuous combat damage. Lieutenant Commander Mitsuo Fuida, the air commander who led the Pearl Harbor attack and survived the war, later wrote in his memoirs, “We never understood how the Americans kept so many ships operational so far from their bases. We sank ships.

We crippled ships and yet their fleet seemed to grow larger. Only after the war did I learn about their floating shipyards. Had we known, we would have made them priority targets. But by the time the docks entered service, Japan had lost the ability to conduct offensive operations against rear area targets. The American advance had pushed Japanese air power back beyond striking range of places like Ulithi.

The floating factories operated in perfect safety, unknown and untouchable. The philosophy behind the ABSDS emerged from a uniquely American approach to industrial warfare, the understanding that logistics and sustainability matter more than individual combat power. In 1941, when Commodore Olsen first proposed the sectional dock concept, he was solving a problem that traditional naval thinking couldn’t address.

The standard response to battle damage was to build more ships to replace those lost or removed from service. But ship construction took years. A replacement carrier required 24 months from keel laying to commissioning. America didn’t have 24 months in 1942. Olsen’s insight was that repairing a damaged ship was vastly more efficient than building a new one.

An Essexclass carrier represented 900,000 man-h hours of construction labor and 15,000 tons of specialized steel. If that carrier could be repaired in the forward area in 2 weeks instead of removed from service for 4 months, it was equivalent to having built a second carrier. The mathematics were brutally simple. The Pacific Fleet would operate an average of 4,000 m from Pearl Harbor during the Central Pacific Drive.

At a cruising speed of 15 knots, a damaged ship required 276 hours, 11 12 days just to reach Pearl Harbor. Add 2 months for repairs and 11 more days for the return journey, and a single repair took 90 days minimum. During those 90 days, that ship’s contribution to fleet striking power was zero. A forward floating dock eliminated the travel time entirely.

A ship damaged at 0800 hours could be inside a floating dock by 1600 hours that same day. Repairs that required the full facilities of a major shipyard still meant a return to Pearl Harbor. But repairs that could be accomplished with the resources available at an advanced base, and that category included the vast majority of battle damage, could be completed in days or weeks instead of months.

The design requirements were extraordinary. Lift capacity minimum 90,000 tons to handle an Iowa class battleship fully loaded. Clear width 240 ft to accommodate the widest beam of any American capital ship. Sectional construction. individual sections no larger than 100 ft by 80 ft to fit aboard standard cargo ships. Operating depth capable of ballasting to 60 ft to lift ships drawing 35 ft.

Structural strength. Wing walls capable of supporting the distributed load of a 45,000 ton ship. Power generation. Self-sufficient electrical generation for pumps, workshops, and lighting. Crew facilities. living spaces for 400 officers and enlisted men. Assembly time capable of being assembled by CB battalions in less than 30 days.

The Bureau of Yards and Docks awarded the contract to Pacific Bridge Company of San Francisco with final design work completed by the Navy’s own engineers at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. The lead naval architect was Captain Howard Mast, who had designed several of the Navy’s existing graving docks at majorshore facilities.

Mast’s crucial innovation was the internal cradle system. Traditional dry docks used wooden blocks positioned under a ship’s keel, supporting the vessel at multiple points along its length. This approach required precise knowledge of each ship’s internal frame structure and careful positioning of blocks before the dock was pumped dry.

Get it wrong and you could crack a ship’s keel under its own weight. The ABSD design used a flexible cradle system with multiple adjustable supports that automatically distributed the load based on the ship’s actual weight distribution. Shore timbers were still required for lateral support, but the risk of catastrophic structural failure during lift operations was dramatically reduced.

Each section’s ballast tanks were independently controlled, allowing operators to adjust the docks level in real time during the lift process. If one section began taking disproportionate load, its tanks could be adjusted to redistribute weight. This flybywire approach to floating dock operations was unprecedented in 1943.

The pumping systems were industrial scale. Each ABSD1 section contained four electrically driven centrifugal pumps, each capable of moving 5,000 gall per minute. With 10 sections, the complete dock could pump 200,000 gallons per minute, allowing it to be ballasted or debalasted in approximately 4 hours. Power came from diesel generators mounted in four of the 10 sections, producing 2,000 kows of electricity, enough to power a small town.

This powered not just the pumps, but also the machine shops, welding equipment, compressed air systems, and lighting that made aroundthe-clock repair work possible. The cost was enormous. ABSD1 required 15,000 tons of steel, 2400 m of electrical wiring, and 14,000 man-h hours of skilled shipyard labor per section.

Total construction cost exceeded $12 million per dock, equivalent to $200 million in 2024. But compared to the cost of building replacement ships, it was trivial. A single Essexclass carrier cost $78 million. An Iowa class battleship cost $110 million. If one ABSD could extend the operational availability of just three capital ships by repairing them in the forward area instead of sending them home, it paid for itself in increased combat power.

Ultimately, the United States built seven complete ABSDs during World War II. ABSD1 through ABSD6 plus several smaller ARD units. They deployed to every major forward anchorage in the Pacific. Espiritu Santo, Manis, Ulithy, late and eventually Okinawa after its capture in June 1945. The design philosophy was pure American industrial warfare.

Solve problems with engineering and logistics rather than simply accepting them as unchangeable facts of combat. The ocean was too wide. Build docks that could cross it. Ships take months to repair. Build repair facilities at the front line. The enemy thinks distance is their ally. Eliminate distance as a factor.

The operational consequences of the floating factories became clear throughout 1944 and 1945. As the tempo of Pacific combat intensified at Uli alone, ABSD1 repaired 159 ships between November 1944 and August 1945. The list reads like a roll call of the Pacific Fleet. The carriers Enterprise, Yorktown, Intrepid, and Hancock.

The battleships South Dakota, Massachusetts, and Indiana. The cruisers San Francisco, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh. dozens of destroyers and destroyer escorts. Each repair represented a ship that remained in the combat zone instead of steaming 7,600 m round trip to Pearl Harbor. The destroyer USS Hugh W Hadley provides a particularly dramatic example.

On May 11th, 1945, off Okinawa, the Hadley was attacked by an estimated 156 Japanese aircraft in a desperate mass kamicazi assault. The destroyer shot down 23 aircraft confirmed with probable credit for 30 more before kamicazis struck her four times. One aircraft hit the forward deck, blowing a hole to the waterline.

A second smashed through the after gun mount. A third exploded against the superructure. A fourth penetrated to the engine room, starting catastrophic flooding. The Hadley’s crew managed to save their ship, but she was a floating wreck. Her commanding officer, Commander Baron J. Melany, expected to receive orders to return to Pearl Harbor for 6 months of reconstruction.

Instead, on May 20th, the Hadley was towed into ABSD4, which had been positioned at Karamarto, a small island group seized specifically to provide forward repair facilities for the Okinawa campaign. For 41 days, CB crews worked around the clock. They replaced entire sections of hole plating. They rebuilt the forward superructure from frames up.

They installed replacement gun mounts shipped from Pearl Harbor. They rewired, replplumbed, and essentially reconstructed half the ship. On June 30th, the Hadley was refloated, and began sea trials. On July 8th, she returned to active duty with the radar picket line off Okanoa. A repair that would have required 6 months at PearlHarbor or the West Coast was completed in 7 weeks with the ship never leaving the immediate combat zone.

The mathematics of this force multiplication are staggering. During 1945 alone, the various ABSDs and ARDs deployed across the Pacific repaired damage that if sent back to Pearl Harbor or the West Coast would have removed approximately 240 ship months of combat capability from the fleet.

By keeping ships in the forward areas, the floating factories effectively added the equivalent of 20 additional destroyers, seven cruisers, and two carriers to the fleet’s operational strength. From the Japanese perspective, the consequences were devastating. Their entire attrition strategy collapsed. When a kamicazi pilot successfully struck an American carrier in early 1945, he had performed at the highest level of skill and sacrifice. The mission was a success.

The ship was clearly damaged, often heavily. And then two weeks later, that same carrier would be back on station launching strikes. Vice Admiral Maté Ugaki, commander of the fifth airfleet during the kamicazi campaigns, wrote in his diary in June 1945, “We damage them, they return. We sink them, new ships appear.

We cannot understand how they maintain such strength so far from their homeland. It is as if they possess some supernatural power of restoration.” The supernatural power was 15,000 tons of sectional floating steel and 400 CBS per dock, working in three shifts, 24 hours a day in tropical heat and torrential rain, rebuilding ships while the sounds of combat echoed over the horizon.

The [snorts] specific instances tell the story. February 21st, 1945. The carrier Saratoga is hit by five kamicazis off Ewima. 123 men are killed. The forward flight deck is wrecked and the ship suffers massive fires. Expected repair time at Pearl Harbor, 3 months. Actual repair time at ABSD1 Uli, 36 days.

March 19th, 1945, the carrier Franklin is hit by two bombs off Kyushu, Japan. The forward third of the ship erupts in a massive explosion that kills 724 men and comes within minutes of sinking the vessel. The Franklin manages to reach Ulathy on her own power, where initial damage assessment determines she requires complete reconstruction only possible at a major shipyard.

She is sent to Pearl Harbor, then to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. But her ability to reach Ulathy at all was enabled by the knowledge that emergency repairs could be performed there. The floating docks couldn’t fix everything, but they could stabilize ships enough to survive the journey home. April 6th, 1945.

The battleship Maryland is hit by a kamicazi off Okinawa, killing 53 men and causing severe topside damage. At ABSD2, Leego, 23 days of repair, returns to combat operations. May 7th. May 4, 1945. The cruiser Birmingham is hit by a kamicazi that kills 51 men and destroys her forward fire control systems. At ABSD1, Uly, 19 days of repair, the pattern repeated dozens of times throughout 1945.

Japanese airmen gave their lives in kamicazi attacks that achieved perfect hits, causing devastating damage. and within weeks their target vessels were back in action. The psychological impact on the surviving Japanese pilots and commanders was profound. They were sacrificing everything to strike the American fleet and the fleet refused to diminish.

Lieutenant Sheibata Kazuo, a Japanese naval officer captured on Okinawa, was interrogated about Japanese assessments of damage inflicted on American ships. His response translated in the interrogation report dated July 2, 1945 revealed complete bafflement. We see the bombs hit. We see the fires. We confirm the ships are damaged, but they do not leave. They continue to fight.

We cannot explain this. Some of our officers believe the Americans have learned to repair ships at sea without any port. This seemed impossible, but we have no other explanation. He was more correct than he knew. The Americans had indeed learned to repair ships without ports. They had simply brought the ports to the ships.

The final accounting of the advanced base sectional docks reveals the scale of their impact on the Pacific War. Total ABSDs constructed, seven complete units, ABSD1 through ABSD6 plus ABSD7 completed just before wars end. Total sections 70 individual sections each capable of independent transport. Total ARDs smaller auxiliary docks 33 units ARD1 through ARD33.

Combined lift capacity approximately 550,000 tons equivalent to lifting the entire pre-war Pacific fleet simultaneously. Ships repaired at forward bases. Confirmed records 2,118 vessels from August 1943 through August 1945. Major capital ships repaired. 27 battleships, 43 aircraft carriers, fleet and escort, 86 cruisers.

Combat vessels returned to action. 658 destroyers and destroyer escorts repaired and returned to service in forward areas. Average repair time at forward docks, 18.3 days for major combat damage, 7.2 days for minor damage. Comparative repair time to Pearl Harbor, 63.4 days average,including travel time, 94.7 days average, to West Coast.

Ship months of combat availability preserved. Approximately 3,500 ship months, equivalent to adding 290 additional destroyers to the fleet for one year. personnel assigned to dock operations. 4,800 CBS and Navy personnel across all forward repair facilities. Tonnage of repair materials transported to forward bases.

47,000 tons of steel plate machinery and equipment. The human cost was remarkably light for such extensive operations. The forward floating dock facilities operated for 680 combined days under combat conditions at bases within range of Japanese air attack with only 14 personnel killed and 47 wounded almost all during the kamicazi attacks on Uli and Lee Gulf anchorages.

The docks themselves were never directly hit, partly because the Japanese remained largely unaware of their existence, and partly because the logistics ships and repair facilities were never priority targets compared to combat vessels. The comparative analysis with Allied and Axis capabilities is stark.

The British Royal Navy operated several floating docks in forward areas, but none approaching the capacity of the ABSDs. The largest HMS Malberry was designed for the D-Day invasion, but was optimized for landing craft and light vessels with lift capacity around 10,000 tons. The British could repair destroyers forward. They could not repair battleships or fleet carriers.

The Japanese operated two large floating docks, both at Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan. Both were destroyed by American air raids by mid 1945. The Japanese never deployed floating dry docks to forward bases. partly due to lack of transport capability and partly because their defensive strategy didn’t anticipate fighting so far from home bases.

When Japanese ships were damaged in places like Truck or Rabal, they either repaired them with minimal dock facilities, often inadequately, or attempted to sail them back to Japan, where many were sunk in transit by American submarines. Germany operated several floating docks, but all within European waters, never deploying them to overseas territories.

The German concept of naval logistics focused on returning to port for repair, not bringing repair facilities to forward areas. The philosophical difference is clear. American naval doctrine emphasized sustainability and logistics as core components of combat power. The floating docks were expensive, technically complex, and required significant support infrastructure, but they fundamentally altered the strategic balance by eliminating geography as a Japanese advantage.

One statistical comparison demonstrates the impact. In 1942 1943, before the ABSDS became operational, the average American destroyer damaged in combat remained out of action for 127 days. In 1944 1945 after the forward floating docks were fully deployed that figure dropped to 31 days. The destroyer forc’s effective combat strength increased by approximately 75% without building a single additional ship.

Master Chief Boatzwin’s mate James Hendris, who served aboard ABSD1 from November 1944 through August 1945, described the experience in a 1989 oral history interview. We knew what we were doing mattered. Every ship we fixed was a ship that went back out to fight. We worked 18-hour days, 7 days a week in heat that made you think you were standing in an oven.

But when you’d see a carrier or a cruiser float out of that dock and you knew two weeks ago she was a wreck and now she’s heading back to combat, there’s no feeling like that. We were building victory one ship at a time. The final tally is definitive. The floating dry docks and forward repair facilities added the equivalent of two additional carrier task groups to the Pacific Fleet operational strength without building additional ships.

In a war determined by logistics and industrial capacity as much as combat skill, this represented a strategic advantage the Japanese could never overcome. November 17, 1944. Commander Richard Hayes still stands at the edge of Ulithy Lagoon, watching the USS North Carolina float out of ABSD1, ready to return to combat after just 8 days in the dock.

The war will continue for another 9 months, but the outcome is already determined. Japan’s strategy of attrition cannot work when the fleet they’re trying to attit can repair itself thousands of miles from home. Every torpedo hit that doesn’t sink a ship outright is now a tactical success that produces no strategic benefit. Every kamicazi that damages but doesn’t destroy a carrier has accomplished nothing but the death of the pilot.

The floating factories represent something more fundamental than engineering capability. They represent a completely different philosophy of warfare. American in its pragmatism, industrial in its scale, and devastating in its effectiveness. The Japanese built the finest naval aircraft in the early war years, the Zero Fighter and the Batty Bomber.

Optimized for range andperformance by sacrificing pilot protection and fuel tank armor. They achieved initial dominance at terrible long-term cost. Pilots who should have survived to train the next generation died in easily preventable fires. The Americans built ships and aircraft designed for sustainability. Heavier, slower initially, but able to absorb damage and bring crews home.

And when those ships were damaged, the Americans didn’t accept months of downtime as inevitable. They built floating shipyards and moved them across an ocean. By August 1945, ABSD1 at Ulithy has repaired its 159th ship. Across the Pacific, the network of floating docks and repair facilities has become the invisible foundations supporting the visible fleet.

When the Japanese signed the surrender documents aboard the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, among the assembled fleet are 14 vessels that should have been in Pearl Harbor or the West Coast undergoing months of repairs, but instead were restored to service at forward bases and participated in the final victory.

The ABSDS themselves survived the war and continued serving for decades. ABSD1 was eventually renamed AFDB1, auxiliary floating dry dock big and served at various Pacific locations through the Vietnam War. Several sections remained in service through the 1990s, their massive steel construction proving more durable than anyone had imagined in 1942.

In the final analysis, Commodore Andrew Olsen’s insight was correct. The Pacific War would be won not by the fleet that dealt the most damage, but by the fleet that could sustain itself farthest from home. The floating factories weren’t a secret weapon in the traditional sense. They didn’t sink ships or shoot down aircraft.

But they did something more strategically valuable. They made geography irrelevant. The Japanese counted on distance being their ally. They calculated that every mile from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo worked in their favor. That the vast Pacific would swallow damaged American ships for months at a time, slowly grinding down the fleet combat power through accumulated damage.

What they never counted on was America bringing the shipyard to the war. The examination that began with Commander Hayes standing at Ulithy Lagoon ended with a fleet that could not be worn down by attrition could not be diminished by distance and could not be defeated by a strategy built on geography. The advanced base sectional docks were not revolutionary weapons.

They were something more dangerous, revolutionary logistics. and logistics, not courage or tactics or technology alone, determined the Pacific War’s outcome. In that single truth lies the entire story of how America fought a war 7,000 miles from home by bringing home to the