Germans Said Concrete Ships Would Never Float — Until America Proved Them Wrong

March 15, 1944. Port of Baltimore, Maryland. Lieutenant Commander Robert Hayes stands at the edge of the loading dock, staring at the hull of the vessel morowed before him. His hand reaches out, palm flat against the gray surface, cold, rough, unmistakably concrete. This cannot be what the manifest says.

No Navy would commission cargo vessels made of stone. The SS Vituvius sits low in the water. Her 366 ft length dwarfing the wooden Liberty ships tied up nearby. From a distance, she appears unremarkable. Another wartime freighter among hundreds crowding the harbor. But up close, the truth becomes impossible to ignore.

The hull isn’t riveted steel plates. It’s poured concrete reinforced with steel mesh 5 in thick in places. The surface texture betrays its composition. aggregate visible through the thin patina of marine paint. Small imperfections where forms were removed during construction. Hayes walks the length of the ship. Each step confirms what his mind struggles to accept.

The entire vessel from keel to deck edge, from stem to stern is concrete. Not just the hull, but the superructure, the cargo holds, even portions of the deck. The ship displaces 4,825 gross tons. She’s designed to carry 5,000 tons of cargo and she’s made of the same material used to build bridges in buildings.

A merchant mariner named Richard Powers approaches, seabag over his shoulder. He’s been assigned to Vuvius for her maiden voyage to England. You getting a good look, commander? Powers asks. I’ve been staring at her for 2 days. Still don’t believe it’s going to float with us aboard. Hayes pulls his hand away from the hull. What’s she carrying? Lumber.

Thousands of board feet. I figure if she starts to sink, at least we’ll have something to cling to. The commander doesn’t smile. He’s seen the ship’s specifications. Triple expansion steam engine, 1300 horsepower. Maximum speed 7 knots, slower than most merchant men, but supposedly seaorthy. The Maritime Commission has certified her for Atlantic crossings.

24 of these concrete ships have been built in Tampa, Florida over the past 9 months. The Vuvius and her sister ship, David O. Sailor, are about to become the first to cross an ocean into a war zone. Powers hefts his bag. They say concrete floats as well as steel long as you shape it right. Archimedes principle or something. I just keep thinking about what happens if we take a torpedo hit.

He shakes his head. Steel bends. Steel tears. What does concrete do? It shatters, Hayes thinks, but doesn’t say. Like every sidewalk that’s ever cracked under stress, what happened next for these stone ships sailing into a war zone defied all odds. If you’re invested in this incredible story of wartime ingenuity and desperation, click the like button to support the channel and subscribe so you don’t miss how this incredible saga ends.

Now, back to the reality of these vessels. These ships exist. The Maritime Commission built them. The Navy has accepted them. And in 3 days, they’ll sail for Liverpool as part of a convoy preparing for the largest amphibious invasion in history. The journey to this moment, from desperate drawings to a fleet of stone ships sailing into battle, had begun 2 years earlier when American shipyards faced a crisis that threatened to stop the war effort before it truly started.

The problem became apparent in the summer of 1942. Steel production could not keep pace with wartime demands. The United States was building Liberty ships at extraordinary rates, one every 2 weeks from some shipyards. An achievement that would have been impossible to imagine just years before. But Liberty ships required steel, lots of it.

Approximately 7,700 tons of steel per vessel. By mid 1942, American forces were engaged on multiple fronts. The Pacific War required carriers, destroyers, cruisers, battleships. The Atlantic demanded escorts for convoys running supplies to Britain and Russia. Steel also went to tanks, artillery, aircraft, ammunition. Every branch of service competed for the same limited resource.

The US Maritime Commission faced an impossible calculation. The war effort required cargo capacity, ships to move supplies, equipment, fuel, and food across oceans. But those ships required steel that didn’t exist in sufficient quantities. Alternative materials had to be found. Concrete seemed like madness at first.

The very idea contradicted basic assumptions about naval architecture. Stone sinks. Everyone knows this. Drop a rock in water and it goes straight to the bottom. Building a ship from concrete appeared to violate the fundamental laws of physics. But the physics actually worked. And the United States had proven this once before. During World War I, facing similar steel shortages, the US government had commissioned an experimental concrete ship program.

The Emergency Fleet Program, approved by President Woodro Wilson in April 1918, called for Pharaoh cement vessels, concrete reinforced with steel bars. 43 ships were eventuallyordered. Only 12 were completed, and they came too late for wartime service. But they proved the concept wasn’t impossible. The SS Faith, launched in March 1918 from California, became the first American concrete cargo ship.

At 336 ft long and displacing 3,427 gross tons, she demonstrated that properly designed concrete vessels could carry cargo across oceans. Faith survived an 80 mph gale on her maiden voyage, maintaining course while steel ships sought shelter. She operated commercially for 3 years before economic pressures, not structural failures, ended her service.

The World War I concrete ships failed not because of engineering flaws, but because of economics. They required less steel than conventional vessels, but used more labor to build. They displaced more water for the same cargo capacity, requiring more fuel to operate. In peace time, with steel abundant and fuel costs critical, they couldn’t compete.

But 1942 wasn’t peace time, and the calculations had changed. On May 1st, 1942, the Maritime Commission reviewed proposals for emergency ship building programs using alternative materials. Concrete ships were on the list. So were wooden ships and even experimental designs using aluminum. Commission engineers examined the World War I concrete ship data.

The structural approach had been sound. 30 years of advancement in concrete technology, better aggregates, improved mixing methods, refined reinforcement techniques meant that new concrete ships could be lighter and stronger than their predecessors. The mathematics were compelling. A concrete ship used approximately 45% less steel than an equivalent all steel vessel.

The steel went entirely into reinforcement mesh, not hall plating. Concrete itself was abundant. Sand, gravel, cement could be sourced domestically without straining war production. And unlike Liberty ships, concrete vessels didn’t require specialized shipyard infrastructure. They could be built at facilities that had never constructed ships before, using workers trained in concrete construction rather than steel fabrication.

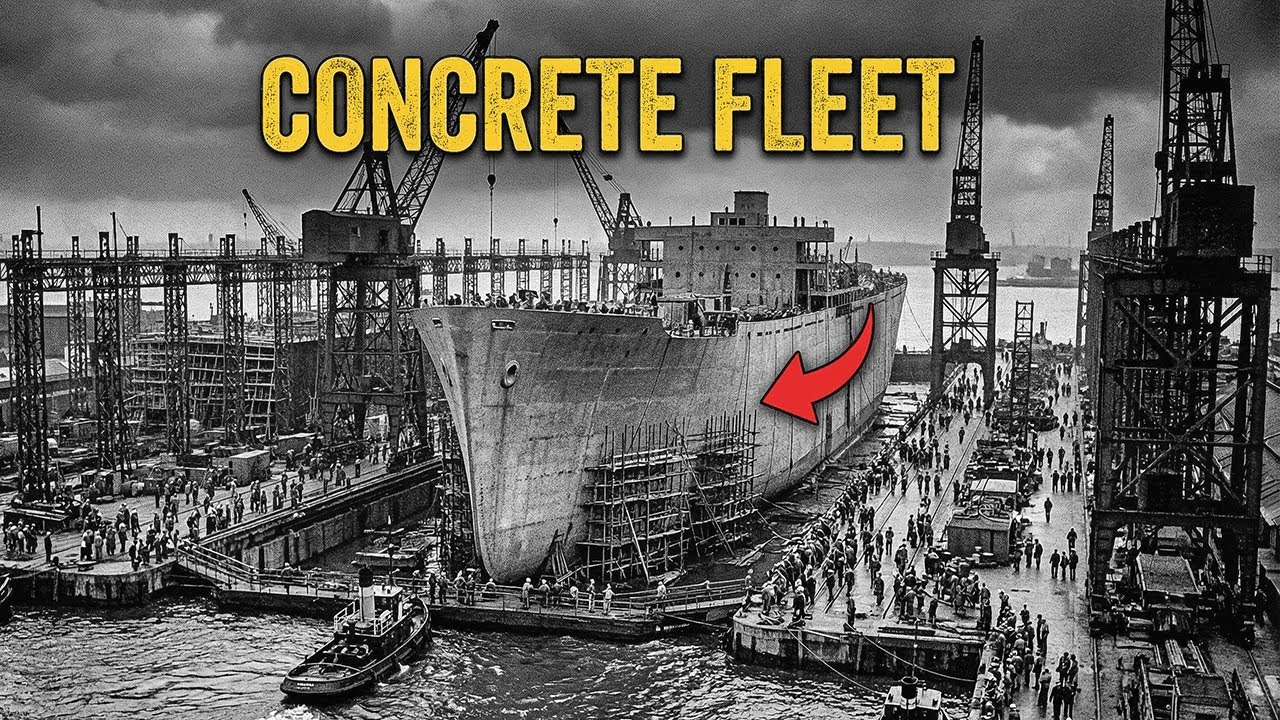

On August 12th, 1942, the Maritime Commission approved contracts for concrete ship construction. The initial order specified 24 self-propelled cargo vessels and multiple barges. Additional contracts went to California shipyards for concrete barges, but the largest contract went to McClosky and Company of Philadelphia. Matthew H.

McCloskkey ran a major construction firm that had built the Philadelphia Convention Hall and the Washington DC stadium. His company understood large-scale concrete work, but they’d never built ships. The learning curve would be steep. The Maritime Commission gave them a location, Hooker’s Point in Tampa, Florida, where the Tampa Port Authority leased land for a new shipyard.

Construction of the shipyard began before final designs were approved. McCloskkey and company needed to build the facility first. Ways for constructing vessels, concrete mixing plants, steel fabrication shops for reinforcement mesh, cranes, railway spurs to bring in materials. At peak operation, the yard would employ 6,000 workers across 13 separate buildingways.

The ship design itself was designated C1 SD1. The specification called for vessels 366 ft long with a 54 ft beam, steam powered using a threecylinder triple expansion engine producing,300 horsepower. Maximum speed 7 knots. Displacement 4825 gross tons. Dead weight capacity 5,000 tons of cargo.

The holes would be constructed using reinforced concrete steel mesh embedded in poured concrete creating a composite material stronger than either component alone. The concrete provided compressive strength and protected the steel from corrosion. The steel provided tensil strength preventing cracks from propagating. Together they could withstand the stresses of ocean voyages, wave action, cargo loading, temperature changes.

Construction began in July 1943. The first ship, yard number one, took form on the ways. Workers bent steel reinforcement bars into complex three-dimensional meshes following precise engineering drawings. These meshes were assembled inside wooden forms that defined the hole shape. Then the concrete was poured section by section building up the hull from keel to deck edge.

The ships were named after pioneers in concrete science and engineering. Vituvius Polio a Roman engineer from the 1st century BC who wrote about building materials. David O Sailor who patented a process for making Portland cement in the United States. Names that honored the material that made these vessels possible. By early 1944, the first ships were complete.

On paper, they met all specifications. They floated, their engines ran, they could carry cargo. But theories and calculations meant nothing compared to actual performance. These ships had to cross oceans, potentially through submarinefested waters, carrying supplies critical to the war effort. The SS Vituvius and SS David O.

Sailor would be the test cases. If they succeeded,the concept would be proven. If they failed, if concrete ships proved too fragile, too slow, too unreliable, the entire program would become another wartime experiment that consumed resources without delivering results. The crossing began on March 5th, 1944. The Vituvius departed Baltimore as part of convoy CK2 bound for England.

The ragtag flotilla consisted of 15 vessels, World War I era hog islanders, damaged Liberty ships pressed back into service, a dredger undertoe, two floating cranes, and the concrete ship Vituvius carrying lumber. The David O sailor followed shortly after with a cargo of super phosphates, fertilizer that Britain desperately needed for agriculture.

The two concrete ships would make the crossing separately but toward the same ultimate destination, the staging areas for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy. Richard Powers, the merchant mariner aboard Vituvius, watched the convoy form up. It wasn’t a pretty sight, he later recalled. We looked like a floating junkyard.

Old rust pots from the last war limping along. I reckon the Yubot wouldn’t be stupid enough to waste their torpedoes on us. The Atlantic crossing in early 1944 remained dangerous despite Allied progress in the Battle of the Atlantic. German Yubot still prowled shipping lanes. Convoys traveled at the speed of their slowest vessel.

The Vituvvious with her maximum 7 knot speed qualified as that slowest vessel. The entire convoy would crawl across the ocean at her pace. The first days at sea tested everyone’s faith in concrete. The North Atlantic in March offers nothing gentle. Swells running 20 ft. Wind gusts above 40 knots.

Conditions that make steel ships groan and flex. Powers and the crew waited for sounds of distress, creaking, cracking, water intrusion. But the concrete hull behaved differently than steel. No vibration. Steel ships transmit engine vibrations throughout the hull. Every rivet, every plate resonates with the rhythm of the machinery.

Concrete absorbed those vibrations. The Vituvvious moved through heavy seas with an eerie smoothness. The hull didn’t flex noticeably. It rode through waves like a massive solid block. One old gentleman in Liverpool, when the Vuvius finally docked after 33 days at sea, tapped the hull with his cane to verify it was actually concrete.

He couldn’t believe what he was seeing. a ship made of the material used to build sidewalks and foundations floating calmly in the harbor after crossing the North Atlantic in winter. The David O sailor completed her crossing in 37 days without significant incident. Both ships arrived intact.

No structural failures, no leaks beyond what pumps could handle, no catastrophic failures. But arrival in England meant entering a new phase. The ships weren’t coming to England to serve as cargo vessels. They had a different purpose, one that would take advantage of concrete’s unique properties in ways the designers hadn’t originally intended.

Army engineers came aboard with cases of dynamite. They began preparing demolition charges, placing them strategically in the cargo holds. The concrete ships were being converted into block ships, vessels to be intentionally sunk as part of the artificial harbor system for the Normandy invasion. The concept was elegant in its simplicity.

The invasion beaches would have no port facilities. Everything needed, troops, vehicles, supplies, ammunition would have to come directly over the beaches. But the English Channel wasn’t calm water. Storms could halt operations for days. Ships needed protected anchorages close to shore. The solution was called the Malberry Harbor, an artificial port constructed by sinking ships to create breakwaters.

The concrete ships were perfect for this role. They wouldn’t rot like wooden vessels. They were large enough to create significant barriers against waves, and unlike steel ships, they could be sacrificed without losing valuable steel that could be salvaged. The Vituvius and David O sailor joined other block ships at Portsmouth preparing for D-Day.

The invasion launched on June 6th, 1944. The concrete ships followed shortly after. On D-Day plus 1, June 7th, 1944, the David O sailor attempted to maneuver into her assigned position off Utah Beach. German 88 mm artillery opened fire. Shells exploded around the concrete ship, sending up geysers of water. The vessel withdrew.

Another attempt on D-Day plus 3 ended the same way. German guns had the range and shells straddled the ship. Finally, on D-Day plus 4, June 8th, 1944, conditions allowed the operation to proceed. Army engineers detonated the charges. The David O sailor settled quickly into shallow water, her hull breaking the surface, forming part of the breakwater designated Gooseberry 1 off Utah Beach.

The Vituvius followed, sinking to create a protected anchorage for supply ships. A Navy chaplain, Lieutenant Leroy Arthur Gml, boarded the partially submerged David O. Sailor shortly after she settled. He removedthe ship’s wheel as a souvenir of the invasion. That mahogany wheel 36 in in diameter with brass fittings and an engraved manufacturer’s plate reading American Engineering Co.

Filla became a tangible memorial to the concrete ship’s contribution to the war’s largest amphibious operation. The Normandy block ships proved the concept in ways that surprised even the Maritime Commission engineers. Concrete performed exceptionally well underwater. The material didn’t corrode like steel. It provided massive stable structures that broke wave action effectively.

The artificial harbors worked, but the Normandy operations represented only two of the 24 concrete ships built in Tampa. The remaining vessels entered service in different roles, and their performance revealed both the advantages and limitations of concrete construction. Several ships served as floating warehouses in Pacific theater operations.

The concrete hulls, impervious to tropical heat and humidity, made excellent storage facilities. Ships were stationed at forward bases filled with supplies and left anchored for months at a time. The concrete didn’t rust. It didn’t require constant maintenance like steel hulls. For static storage roles, the ships were nearly ideal, but operational use exposed problems.

The 7 knot maximum speed that seemed acceptable on paper became a severe limitation in practice. Concrete ships couldn’t keep pace with conventional cargo vessels. They required dedicated escort vessels if they traveled independently. In convoy, they slowed everyone else down. The weight disadvantage also became apparent.

A concrete ship carrying 5,000 tons of cargo displaced far more water than a steel ship carrying the same load. More displacement meant more fuel consumption. The inefficiency wasn’t catastrophic, but in a war where fuel logistics determined operational capability, every inefficiency mattered. Lieutenant James Morrison, assigned to supervise cargo operations at any Watak atal in the Marshall Islands, worked with two concrete barges designated for unclassified miscellaneous.

The USS Trefoil and USS Quartz served as floating supply depots. They sat there like islands, Morrison later wrote. Completely stable. We could load and unload in any weather, but moving them that required tugs. They were too heavy and slow to manage under their own power in harbor conditions. The concrete ships and barges filled niche roles effectively.

When speed wasn’t critical, when the primary requirement was carrying capacity and stability, concrete worked. The material proved durable in ways steel wasn’t. Sailors noted that concrete holes stayed cooler in tropical sun. The thermal mass absorbed heat slowly, making interior spaces more tolerable.

In the Pacific, where ships served as floating bases for months, this mattered enormously. But concrete ships would never replace steel vessels. They were supplements. stop gap measures to address temporary steel shortages. As Liberty ship production ramped up through 1944, the advantage of concrete construction diminished.

Liberty ships, despite requiring more steel, could be built faster once production lines were fully established. They were faster, more maneuverable, and more fuel efficient. The Navy even commissioned an extraordinary concrete barge, a floating ice cream parlor built in 1945 for service in the Western Pacific.

The barge could produce 10 gallons of ice cream every 7 seconds. The facility cost over $1 million to construct. It served troops across multiple island bases, delivering a morale boost that commanders considered worth the investment. The concrete construction made sense for a stationary facility that needed to protect delicate refrigeration equipment from tropical conditions.

By late 1944, the strategic calculus had shifted. Steel production had increased. Liberty ship construction had become routine. The urgency that made concrete ships necessary in 1942 had eased. The Maritime Commission didn’t cancel the concrete ship program, but they didn’t expand it either. The 24 ships built in Tampa represented the totality of the World War II self-propelled concrete fleet.

The ships served. They performed their assigned roles. They proved that concrete could work as a ship building material. But they also proved that concrete ships were a wartime expedient, not a revolution in naval architecture. The engineering behind the concrete ships represented 30 years of accumulated knowledge about pharaoh cement construction.

The World War I experiments had revealed basic principles. The World War II implementation refined those principles to create workable vessels. The fundamental challenge was making a brittle material behave like a ductile one. Concrete excels in compression, squeezing it together, but fails catastrophically under tension, pulling it apart. Steel is the opposite.

Excellent in tension, relatively weaker in compression. Combining them created a composite material that leveraged bothstrengths. The hull construction began with steel reinforcement mesh. Workers fabricated three-dimensional frameworks using steel bars between 1/2 in and 3/4 in in diameter.

These bars were bent, shaped, and welded into precise geometries that followed the curves of the hole design. The spacing between bars mattered enormously. Too far apart and the concrete could crack between them. too close together and concrete couldn’t properly fill the spaces. The mesh was assembled inside wooden formwork.

These forms built from Oregon pine to minimize warping in Tampa’s humid climate defined the external shape of the hull. The forms had to be exceptionally strong. Wet concrete weighs approximately 150 lb per cubic foot and the pressure against formwork could reach thousands of pounds per square foot. Concrete placement required careful attention to mix design and pouring technique.

The concrete needed to be fluid enough to flow into every space around the reinforcement, but stiff enough not to slump or separate. Air bubbles had to be eliminated. Any voids would create weak spots. Workers used pneumatic vibrators, holding them against forms near pouring points. The vibration liquefied the concrete temporarily, allowing it to fill completely while forcing trapped air out.

The hull thickness varied by location. Bottom plates were approximately 4 1/2 in thick. Side plates ranged from 3 1/2 to 5 in depending on structural requirements. Bulkheads, the internal walls dividing the ship into compartments, were concrete as well, creating watertight divisions. The ships used what engineers called lightweight aggregate concrete, though sources don’t specify the exact materials.

Standard concrete uses stone aggregate, crushed rock, which is heavy. Lightweight aggregates can include expanded clay, shale, or even volcanic materials, all of which reduce density while maintaining strength. The weight savings were critical. Every pound saved in hole weight translated to either increased cargo capacity or reduced draft.

The entire hall from keel to deck edge had to cure properly. Concrete gains strength over time through a chemical process called hydration. Portland cement reacts with water forming crystallin structures that bind the aggregate together. The process generates heat in massive pores like ship holes. This heat had to be managed carefully to prevent thermal cracking.

Historical records from the San Diego World War I concrete ship program document the use of continuous pouring techniques where work proceeded around the clock for days to complete hole sections without interruption. This eliminated cold joints, weak seams where one poured and another began. While specific construction techniques for the Tampa ships aren’t fully documented in available sources, the engineering principles remained consistent.

Minimize joints, ensure proper curing, maintain quality throughout. The propulsion system was conventional steam, triple expansion engines. Proven technology from the age of coal fired vessels converted steam pressure into mechanical rotation. These engines were inefficient compared to modern diesel power, but used widely available components.

The ships burned fuel oil, not coal, making them easier to operate than World War I era steamers. The design philosophy behind these ships can be summarized simply. Build the largest possible cargo vessel using minimum steel, accepting trade-offs in speed and efficiency, optimized for conditions where those trade-offs matter least.

The ships weren’t meant to be elegant or efficient. They were meant to exist when steel vessels couldn’t. The 24 ships completed at Tampa between 1943 and 1944 entered service across multiple theaters. Their fates varied widely, reflecting the diverse ways concrete vessels could be employed. Beyond the Vituvius and David O sailor, which became Normandy block ships, other vessels served in the Pacific.

The USS Quartz operated as a supply barge at various forward bases. She participated in Operation Crossroads in 1946, the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atal, serving as a target vessel. The explosions didn’t destroy her. She survived, damaged, but intact, demonstrating concrete’s resistance to blast effects. The Emil N.

Vidal, completed in 1944 as the last concrete ship built, served as a store ship in the South Pacific. She lost her propeller during operations and had to be towed back to the United States. This highlighted a persistent problem. Repairs to concrete ships required specialized expertise. A damaged steel hole could be patched by any shipyard with welding equipment.

Damaged concrete required concrete repair expertise which most naval facilities didn’t have. Several ships served as training vessels. The Arthur Newell Talbett was used on the West Coast to train merchant mariners in cargo handling procedures. The Robert Wittman Leslie served first as an army training ship, then as a Pacific store ship.

The Edwin Thatcherbecame another Pacific supply depot supporting operations against Japan. But the concrete ship’s greatest contribution came after the war ended. When the ships were no longer needed for military purposes, they found new roles as breakwaters and harbor protection. Kiptopek, Virginia received nine concrete ships in the late 1940s. The vessels were stripped of engines and equipment, then scuttled in shallow water to form a breakwater protecting a ferry terminal.

The names that honored concrete pioneers Arthur Newell Talbot, Robert Wittman Leslie, Willis A. Slater, Edwin Thatcher became anonymous hulks, marking the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. Local fishermen used them as landmarks. The concrete shells persisted decade after decade, slowly deteriorating, but still functional.

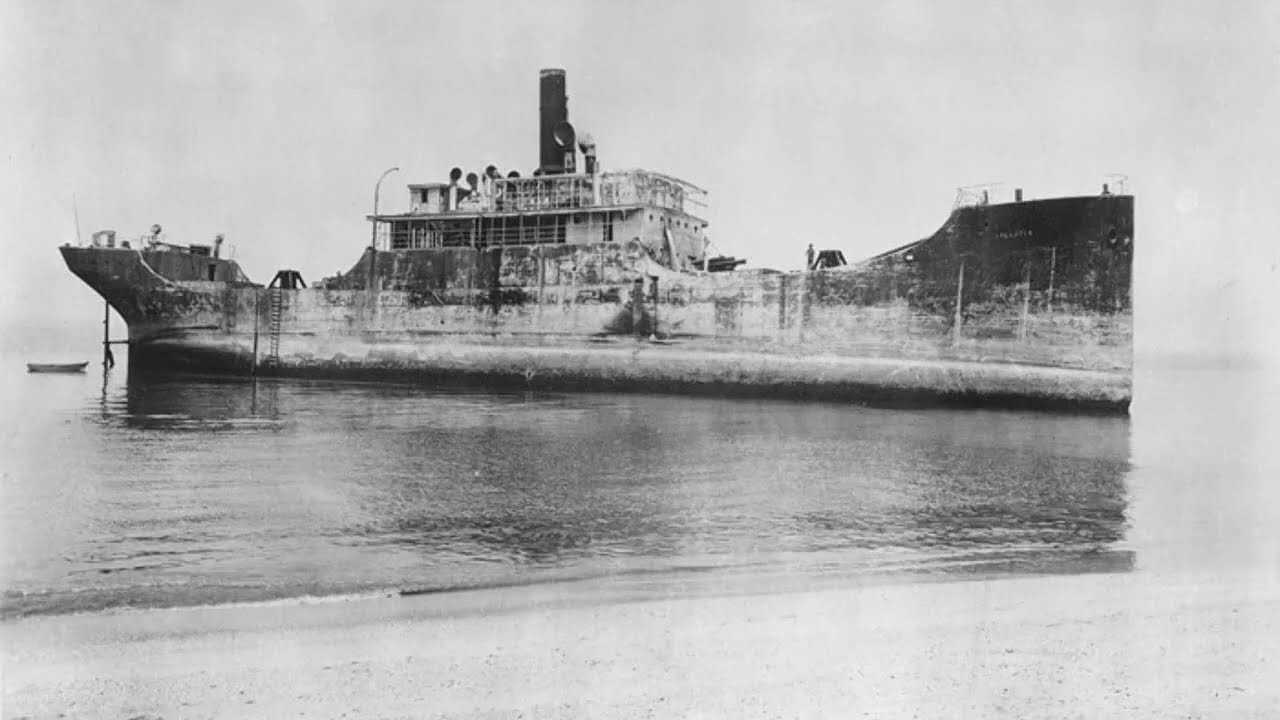

Powell River, British Columbia, acquired the largest collection of concrete ships in the world. A pulp and paper mill needed a breakwater to protect its log storage pond. The company purchased multiple concrete vessels, including both World War II ships and one World War I survivor, the SS Peralta, an oil tanker launched in 1921.

10 concrete ships eventually formed the Powell River Breakwater. USS Yogan 82, SS Henry Lachetta, USS Quartz, USA PM Anderson, SS Peralta, SS Emil Nidel, USA John Smeen, SS Thaddius Maramman, SS LJ Vikat, and SAT Armand Consider. They were filled with water or ballast, anchored with 16 ton concrete anchors, 8 to 10 anchors per ship, and positioned in a semicircle to break wave action.

The concrete holes proved remarkably durable. Exposed to Pacific Ocean conditions for decades, they required minimal maintenance. Steel ships would have rusted away within years. The concrete vessels lasted generations. The Peralta remained afloat for over 90 years before being intentionally sunk in 2018 to create an artificial reef for scuba divers.

This longevity represents concrete’s fundamental advantage as a marine construction material. Properly designed concrete structures in water can last centuries. The material doesn’t corrode. Saltwater exposure doesn’t weaken it significantly. Marine growth attaches to the surface, but this doesn’t compromise structural integrity. The ships that seemed like desperate wartime expedience became permanent maritime infrastructure that outlasted most steel vessels of their era.

In 2018, the USS Yogan 82 was deliberately sunk off Powell River to create an artificial reef. Divers now explore her interior, swimming through cargo holds that once stored military supplies. The concrete hull sits on the seabed at 90 to 100 ft depth, intact and recognizable 74 years after her launch.

She provides habitat for octopuses, rockfish, and other marine life. Her transformation from wartime barge to artificial reef demonstrates the ultimate adaptability of these concrete vessels. The ships served in war. They served in peace. They continued to serve in death as marine habitat and diving destinations. This utility across such different roles reflects the fundamental soundness of the engineering.

The ships weren’t optimal for any single purpose, but they were adequate for many purposes. A flexibility that proved more valuable than anyone anticipated when construction began in 1943. 24 C1 SD1 self-propelled concrete ships were built at McCloskey and Company in Tampa. All 24 were completed and entered service between late 1943 and 1945.

This completion rate stands in sharp contrast to the World War I program where only 12 of the planned 43 ships were finished. The ship’s technical specifications remained consistent across the fleet. Length 366 feet. Beam 54 feet. Displacement 4,825 gross tons. Dead weight capacity 5,000 tons.

Propulsion three-cylinder triple expansion steam engine 1300 horsepower. Maximum speed 7 knots. Hole thickness 3 1/2 to 5 in of reinforced concrete. In addition to the self-propelled ships, the wartime concrete program included numerous barges. California shipyards built concrete barges for various purposes. The specifications varied. B7 A1 barges 366 feet long, 55 ft beam, 4,968 gross tons, 11 built.

B7 A2 barges 375 ft long, 56 ft beam, 5,410 gross tons, 22 built. B5BJ1 lighters 265 ft long, 48 foot beam, 2,630 gross tons, 22 built. B5BJ2 refrigerated lighters, 265 ft long, 48 ft beam, 2,630 gross tons, three built. B5BJ3 lighters 265 ft long 48 ft beam 2,630 gross tons 2 built. B7D1 barges 366 ft long 54 ft beam 4,338 gross tons 20 built.

In Britain, 495 Pharaoh cement barges were constructed during World War II, primarily 84 foot vessels designed to carry cargo or fuel. These smaller craft played crucial roles in the D-Day landings and subsequent logistics operations. The total concrete ship and barge production across all Allied nations likely exceeded 600 vessels.

The program represented a significant commitment of resources, not steel, but labor, cement, concrete, and industrial capacity. Survival statistics tell the remarkable story of concrete durability. Of the 24 Tampa ships, twowere sunk as Normandy block ships, intentional, nine survive as the Kipekc breakwater.

Multiple vessels survive at Powell River. Exact number varies as some have been recently removed. Several were scrapped or abandoned at various locations. None were lost to enemy action. None suffered catastrophic structural failures during operation. This represents an extraordinary survival rate. Compare this to Liberty ships where German Yubot sank hundreds and many others were lost to weather, collisions or mechanical failures.

The concrete ships proved almost indestructible through normal use. The construction cost per vessel isn’t fully documented in available sources, but the comparison to Liberty ships is instructive. Liberty ships cost approximately $2 million each to build and required about 7,700 tons of steel. Concrete ships used about 45% less steel, but required more labor and time to construct.

The economic calculation favored steel ships in any scenario where steel was available. But concrete ships made sense when steel wasn’t available, which was precisely the situation in 1942, 1943. The philosophical difference between American and German approaches to material scarcity is worth noting. Germany also faced steel shortages, but chose different solutions.

They built more submarines using the steel they had, accepting that surface ship construction would suffer. The United States chose to supplement steel ship construction with alternative materials, maintaining cargo capacity even when steel was scarce. Neither approach was inherently superior. They reflected different strategic priorities.

Germany needed offensive weapons, yubot to sink allied shipping. America needed cargo capacity, ships to deliver supplies supporting global operations. The concrete ship program succeeded in its limited goal, maintaining cargo capacity during a critical period. The program was never intended to replace steel ships only to supplement them temporarily.

By 1945, with steel production at maximum capacity and Liberty ship construction routine, concrete ships were no longer necessary. No additional concrete cargo vessels were ordered after the original 24. The program ended when the crisis that created it ended exactly as planned. March 15th, 1944, Baltimore Harbor. Lieutenant Commander Robert Hayes stands with his palm against the concrete hull of the SS Vituvius.

Feeling the cold roughness of aggregate and cement, the ship that seemed impossible now seems inevitable. A logical solution to an impossible problem. Richard Powers boards with his seabag, ready for the crossing that will take 33 days. The lumber in the hold, the concrete hall, the slow transit across a dangerous ocean, all of it represents America’s wartime industrial improvisation.

Build what works with what you have. Accept limitations, deliver results. The Vituvius survives the crossing. She reaches England. Army engineers place demolition charges. On June 8th, 1944, D-Day plus4, the charges detonate. The ship settles into shallow water off Utah Beach. Hull breaking the surface, forming a breakwater that protects supply ships for months afterward.

Her final service is the one for which concrete proved most suited. A permanent structure in the sea. The David O. Sailor carrying super phosphates to feed Britain’s agriculture ends the same way. sunk deliberately, transformed from cargo vessel to fixed maritime infrastructure. The wheel Lieutenant Geml removed remains in a collector’s hands, a tangible piece of history from ships most people never knew existed.

Today, in Kipto Peak, Virginia, nine concrete ships mark the harbor entrance. Fisher circle them. Tourists photograph them. The ships have outlasted most of the steel vessels built during the same period. Concrete doesn’t corrode. It doesn’t rust. It persists in Powell River, British Columbia.

The remaining concrete ships formed the world’s largest floating breakwater. The SS Peralta, launched in 1921, stayed afloat for 97 years before being intentionally sunk in 2018. Divers now explore her interior, swimming through holds that once carried oil across the Pacific. Marine life has claimed her. Octopuses make homes in her compartments.

She has transitioned from ship to reef, still serving, still functional, still fulfilling purposes a century after her construction. The concrete ships were never beautiful. They were never elegant. They were never optimal by any engineering metric except one. They existed when steel ships could not. In total war, that single advantage justified everything.

The ships proved that when conventional solutions aren’t available, unconventional solutions can work, not perfectly, but adequately. The examination of the Vituvius in Baltimore Harbor that March day in 1944 revealed a fundamental truth about wartime innovation. Desperation drives creativity. Limitations force adaptation.

The United States faced a steel shortage that threatened to haltthe war effort. Engineers responded by building ships from the one abundant material available, concrete. The ships worked, they served, they survived. The concrete ships weren’t poorly designed. They were brilliantly designed to achieve specific goals under specific constraints.

Those goals included maximizing cargo capacity while minimizing steel consumption, accepting trade-offs in speed and efficiency that mattered little for supply depot roles. The engineering succeeded completely. The lesson extends beyond ships and beyond World War II. Material scarcity forces innovation. Sometimes those innovations become permanent advances.

Sometimes they remain temporary adaptations, abandoned when scarcity ends. Concrete ships fell into the latter category. When steel became abundant, they disappeared from construction schedules. But they didn’t disappear from the ocean. They remain more durable than anyone predicted, serving new purposes nobody anticipated.

Lieutenant Commander Hayes, standing in Baltimore Harbor in March 1944, couldn’t know that some of these ships would still float 80 years later. He couldn’t know that the desperate wartime measure would produce maritime structures more permanent than most purpose-built infrastructure. He only knew that the ship before him made of stone had to cross an ocean and deliver cargo.

Everything else was theory. The Vituvius crossed that ocean. The theory became reality. And in that crossing, in that service, in that ultimate transformation from cargo vessel to Normandy breakwater, the concrete ships proved that in total war, victory can be built from anything, even stone. The ships made of concrete defied expectations, defied assumptions, and ultimately defied time itself.

They were never meant to last. They lasted anyway. They were never meant to be remembered. We remember them because they represent something fundamental about American industrial capacity in World War II. When the situation demanded the impossible, engineers found a way to deliver something that worked. That’s the entire story of the Stone Fleet.

Not perfect ships, working ships built when they were needed from what was available, serving roles nobody originally imagined and persisting long after their intended purpose ended. The concrete ships were wartime improvisations that became permanent maritime monuments, forgotten by most, but still there, still serving, still proving that sometimes the most unlikely solutions produce the most enduring results. Volts.