America needed a cheap, reliable engine—Packard turned the Merlin into a mass-production machine.

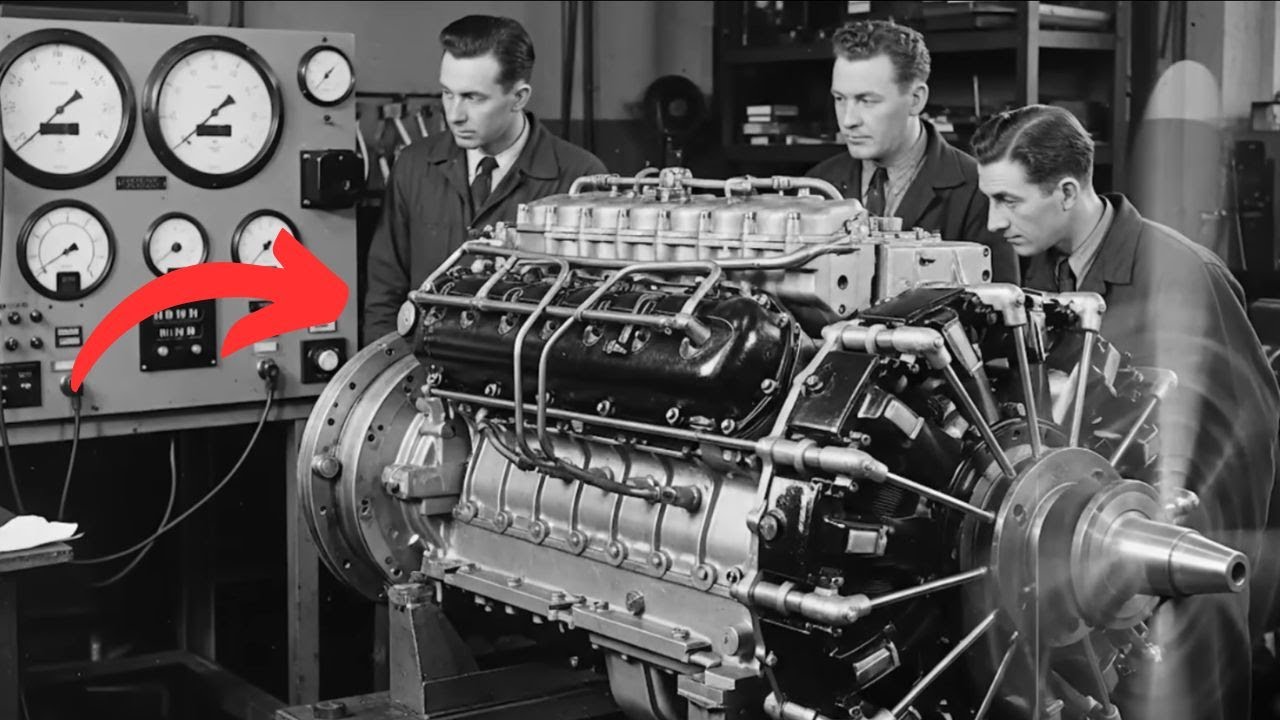

On August 2nd, 1941 in Detroit, Michigan, two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines thundered on the test stands inside Packard Motorcar Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant. But these weren’t Britishbuilt Merlin. They were Americanmade versions constructed from British designs, but entirely re-engineered by Packard’s own team.

The onlookers had no idea they were witnessing the beginning of an industrial breakthrough. Hidden inside those engines were innovations that would reshape the course of World War II. The bearings weren’t the same as the originals. The tolerances were tightened. Even the bolt threads, copied from Britain’s obscure Witworth system, had been reproduced with painstaking precision.

Detroit had just transformed what had once been a meticulously handfitted luxury engine into what would soon become the most mass-roduced power plant in America. And they did it by overturning virtually every principle Rolls-Royce considered inviable. This is the little known account of how Packard’s engineers tackled a seemingly unsolvable problem.

Not by winning battles, but by mastering something even harder. Converting 14,000 finely tuned components from British measurements into American manufacturing standards without losing a single unit of performance. In early 1942, the United States Army Air Forces found themselves in a strange predicament.

They had a fighter aircraft they admired, yet one they couldn’t effectively deploy. The P-51 Mustang, equipped with the Allison V1710 engine, excelled at low altitudes, fast, nimble, and lethal below 15,000 ft. But once it climbed higher, the aircraft struggled, wheezing for oxygen and rapidly losing effectiveness.

The airframe wasn’t at fault. North American aviation had created a masterpiece. The challenge was in the physics of the engine. The Allison relied on a single stage supercharger that simply couldn’t provide enough compressed air at greater heights. At 25,000 ft, where German fighters could maneuver effortlessly, the Allison Mustang was reduced to roughly 1,000 horsepower.

At 30,000 ft, it became practically useless. The tragic irony was that American bomber crews needed fighter aircraft specifically capable of performing at those altitude levels. B17 flying fortresses cruised between 25 and 30,000 ft during missions deep into German territory. Without fighters that could operate effectively at those heights, bombers were being cut down in devastating numbers.

During the August 1943 raid on Schwinfort, 60 bombers were lost in a single day. The Luftwaffa knew exactly how to exploit the Allison Mustang’s limitations. They simply climbed above it and waited. What the United States required wasn’t a new fighter design. It needed a new engine for the aircraft it already possessed. Meanwhile, across the ocean in Derby, England, Rolls-Royce held the answer.

Their Merlin engine powering Spitfires and hurricanes delivered the high alitude performance the Allison could not. Its advantage lay in a two-stage two-speed supercharger system designed by Stanley Hooker capable of maintaining seale pressure all the way to 30,000 ft. But the Merlin wasn’t merely a machine.

It represented a philosophy. Each Rolls-Royce Merlin was effectively handcrafted. It contained 14,000 components, many of which were individually fitted by experienced craftsmen. If a connecting rod didn’t perfectly match a crankshaft, a worker refined it until it did. If bearing clearances varied, adjustments were made by hand.

The British Witworth threading system, with its unusual 55° angle and rounded corners meant every bolt was custom produced. Supercharger tolerances were measured in ranges as tiny as 1/10,000th of an inch, roughly a quarter the thickness of a human hair. Cylinder heads were hand matched to engine blocks. Impellers were manually balanced. This was not mass production.

It was artisal engineering. And Britain simply couldn’t build enough of them. By September 1940, while the Battle of Britain raged overhead, Rolls-Royce factories in Crew, Manchester, and Glasgow ran non-stop around the clock. They were producing 200 engines a week, but they needed 2,000. The British government turned to the United States, hoping American industry could help.

What they did not yet realize was that they were asking Detroit to achieve an engineering feat that seemed almost mathematically impossible, to convert a masterpiece of individual craftsmanship into what would soon become the most mass-roduced power plant in America. And they did it by overturning virtually every principle Rolls-Royce considered inviable.

The real challenge was not in manufacturing engines, but in translating an entirely different engineering mindset into American mass production methodology. When Rolls-Royce personnel arrived in Detroit in September 1940, they came with crates full of complete Merlin, hundreds of blueprints, and unshakable faith in their own techniques.

The licensing deal was valued at $130 million, an enormoussum for the era. Packard was an unexpected choice. The company produced luxury automobiles, not aviation engines. But Packard possessed something Rolls-Royce lacked, expertise in high volume precision manufacturing. As soon as Packard’s engineers reviewed the Merlin drawings, they realized the scale of the task ahead.

They didn’t just face one challenge. They faced around 14,000 of them. The first problem was incompatible measurement systems. Britain used imperial measurements, but not the same imperial system used in the United States. Rolls-Royce specified dimensions in thousandth of an inch. Yet, the standards underlying those figures came from older British engineering principles predating consistent standardization.

Converting those numbers into American specifications wasn’t as simple as arithmetic. It required understanding the purpose behind each tolerance. The second major obstacle was the British Witworth threading system. Every bolt, nut, and threaded joint in the Merlin used a 55 degree Witworth thread form with rounded roots and crests.

In contrast, American unified fine threads relied on a 60° profile with flat roots, meaning the two systems were completely incompatible. Packard had no choice but to manufacture every single fastener themselves, following British specifications exactly. Then came the third and most serious challenge.

Rolls-Royce tolerances were created with the assumption that parts would be hand fitted during assembly. When British technicians built a Merlin, they expected to make adjustments along the way. Variations of several thousands of an inch were perfectly acceptable because craftsmen would simply make components fit.

Detroit’s manufacturing philosophy was the complete opposite. American automotive production depended on absolute interchangeability. Any part had to fit into any engine with no filing, no hand tweaking, no skilled artisan tailoring components by feel. The British engineers remained courteous but doubtful.

Could American factories truly uphold Rolls-Royce’s standards of precision? Packard’s lead engineer, Colonel Jesse G. Vincent, gave them a response they never expected. Their tolerances were actually too loose for American production. The room fell silent. What followed would later become a classic chapter in engineering history.

Packard didn’t merely replicate the Merlin. They reinvented the way it could be produced, all while preserving its essential design. Over the next 11 months, Packard engineers generated 6,000 new technical drawings. Not because Rolls-Royce had made mistakes, but because their designs were incompatible with large-scale manufacturing. Every measurement was redefined.

Every tolerance was tightened. Every production method was redesigned to fit assembly line processes. The brilliance lay in the fine details. Consider the crankshaft bearings. Rolls-Royce used a copper lead alloy that required gentle break-in procedures and regular inspections. Packard’s metallurgists, using data from American aircraft engine development, replaced this with a silver lead alloy treated with an Indian plating.

The silver increased load capacity, while the indium created an ultra smooth microscopic finish that lowered friction and significantly improved break-in behavior. At first, Rolls-Royce protested this wasn’t their specification. But once testing proved that Packard’s bearings ran cooler and lasted longer, Rolls-Royce quietly adopted the American improvement for their own engines.

The threading issue looked impossible to solve. Packard couldn’t convert the Merlin to American thread standards because that would make the engines incompatible with British aircraft and existing spare parts. So they did something extraordinary. They built entirely new tooling capable of producing British threads with American mass-production precision.

Every tap, every dye, every threading tool had to be custommade. Packard even bought specialized British thread measuring instruments and trained their machinists in a threading system none of them had used before. BSW for coarse threads, BSF for fine threads, and BA for small instrument fasteners. The end result was remarkable.

Packard built Merlin used exactly the same thread types as those built by Rolls-Royce. Parts could be swapped freely between engines from Detroit and Derby with complete confidence. But here was the revolutionary part. Packard manufactured British thread fasteners more precisely than Rolls-Royce did. Every piece felt perfectly within its specification.

No hand fitting whatsoever. True interchangeability. Then came the supercharger, the heart of the Merlin’s altitude superiority. The two-stage two-speed design used a pair of impellers mounted on the same shaft and driven through complex gearing. In low gear, the ratio was 6.391:1. When the hydraulic clutch activated high gear, the ratio jumped to 8.095 to1.

These impellers had to be machined and balanced to tolerances measured in10,000 of an inch. When operating, they spun at more than 30,000 RPM. Even the smallest imbalance could destroy the entire engine. Rolls-Royce achieved this through painstaking manual balancing. in which skilled workers added or removed tiny bits of material until the impeller turned flawlessly.

Packard revolutionized this process by developing advanced casting and machining methods that produced impellers so uniform that they required only minimal final balancing. They also built specialized test machinery capable of measuring dynamic balance while the impeller was rotating at speed. The result was dramatically faster production and far more consistent quality.

The intercooler system brought yet another hurdle. Compressing air generates extreme heat up to 205° C. To prevent detonation, the Merlin relied on an elaborate cooling setup involving channels cast directly into the supercharger housing, plus an intercooler core positioned between the supercharger outlet and the intake manifold.

A centrifugal pump circulated 36 gall of ethylene glycol per minute to draw the heat away. Hackard re-engineered the coolant passages to improve flow efficiency and simplify manufacturing without reducing cooling capacity. Every component, every subsystem was studied, redesigned, and optimized for mass production, always without compromising the engine’s performance.

By August 1941, exactly 11 months since the contract was signed, Packard had completed the transformation and was ready. The first Packard built V1650, Packard’s name for the Merlin 20X, ran successfully on a test stand at the East Grand Boulevard plant. When Winston Churchill received word, he reportedly cried with relief.

Britain would finally get the engines it so desperately needed. But proving that one engine worked was entirely different from producing 55,000 of them. Packard reorganized its factory into a masterpiece of precision production. The V1650 assembly line used specialized machining centers, each dedicated to a single task.

One station machined crankshafts, another handled block face milling, another worked on cylinder heads. The American philosophy of automotive manufacturing demanded that every step be measurable and consistently repeatable. If a crankshaft journal was specified at 2.2495 in, then every crankshaft had to measure exactly 2.2 2495.

No deviations to 2.2492 or 2.2498. Absolute uniformity was mandatory. This eliminated the need for the handfitting craftsmanship that Rolls-Royce had relied on in Britain. A Packard line worker didn’t need a decade of apprenticeship. They simply needed solid training and precise equipment. Production grew steadily throughout 1942.

By 1943, Packard was producing engines faster than North American Aviation could manufacture airframes to mount them on. At peak pace, the Detroit plant completed around 400 engines every week, twice the total output of all Rolls-Royce factories in Britain. The V1653, derived from the advanced Merlin 63 with superior high altitude performance, was the power plant that turned the P-51B Mustang into the legendary long range escort fighter.

Its two-stage supercharger allowed the engine to produce well over 1,200 horsepower at 40,000 ft, altitudes where the Allison engine could barely breathe. The most famous version, the V1657, powered the iconic P-51D Mustang with its bubble canopy. Delivering 1315 horsepower at sea level, it pushed the Mustang to 437 mph and maintained combat capability up to 40,000 ft.

Those engines escorted American bomber formations from England to Berlin and back. German pilots called the sound of high altitude Merlin their American Rafugal the American bird of prey and learned to fear it. By the time production finished in 1945, Packard had built 55,523 Merlin engines, more than all Rolls-Royce facilities in the United Kingdom combined.

The Packard Merlin stands as a profound milestone in engineering. It demonstrated that craftsmanship and mass production are not opposites. They can reinforce each other when their underlying principles are understood. Rolls-Royce achieved excellence through meticulous handfitting. Packard achieved excellence through disciplined systems and industrial design.

Both methods produced worldclass engines. But only one approach could meet the overwhelming demands of global war. The innovations Packard pioneered, precision casting, rigorous statistical quality control, and dedicated tooling engineered for consistent output, became foundational to modern aerospace manufacturing. Jet engines powering today’s Boeing and Airbus aircraft are produced using direct descendants of the methods Packard developed in 1941.

Even Packard’s bearing research left a legacy. Their silver lead indium bearings which delivered greater load tolerance and lower friction later became standard in high performance automotive engines. The story of thread compatibility also echoes in the modern world.

Today’s international standardslike metric isometric threads exist because engineers learned during World War II how incompatible fastener systems could logistics. But perhaps the most enduring lesson is philosophical. Packard proved that honoring tradition and embracing innovation aren’t mutually exclusive. They didn’t throw away Rolls-Royce’s expertise. They interpreted it through the lens of American industrial practice.

They kept the British thread system not simply because they were required to, but because engineering integrity demanded full compatibility. That value, prioritizing interoperability and standardization, continues to guide global manufacturing today. Several Packard built Merlin are still running.

The Canadian War Plane Heritage Museum’s Lancaster bomber in Hamilton, Ontario flies with four original Packard engines. At the Reno Air Races, unlimited class P-51 Mustangs equipped with heavily modified Packard Merlin generate more than 3,800 horsepower, almost triple the original rating. Engines built more than 80 years ago continued to operate, proving what American engineering could accomplish when the stakes required the impossible.

The P-51 Mustang is remembered as one of the greatest fighter aircraft of World War II. But its real secret, the reason it dominated the skies over Europe, was not just its elegant airframe or its skilled pilots. Its decisive advantage came from an engine conceived in Derby, England, and refined in Detroit, Michigan.

The story of the Packard Merlin isn’t a tale of one nation outperforming another. It is a demonstration of complimentary strengths. British ingenuity created the Merlin’s groundbreaking design. American manufacturing brilliance delivered it in the overwhelming numbers wartime strategy demanded. 14,000 parts, 6,000 new technical drawings, 11 months of relentless engineering effort.

Together they altered the trajectory of history. And the next time you see a P-51 Mustang flying at an air show, listen closely to the unmistakable howl of its Merlin. That sound represents two engineering cultures working together in perfect unity. British creativity fused with American production expertise to produce something neither could have achieved alone.

If you enjoyed this story, consider subscribing for more deep explorations into the engineering breakthroughs that reshaped warfare. Next week, we’ll uncover another hidden victory of the Invisible War. How American engineers cracked the Japanese Purple Code by building a mechanical computer entirely from scratch despite never having seen the original machine.

Turn on notifications because these aren’t stories about battles won. They’re about how impossible problems were solved.