A Former Wartime Communications Officer’s Hidden Cache Exposes the “Burn Orders,” the Missing Transmissions, and the Quiet Paper Trail That Powerful Men Swore Would Turn to Smoke Forever

The first rule of old secrets is that they rarely arrive with sirens.

They arrive with paper.

The package showed up on a Tuesday, wedged between a grocery flyer and a neighbor’s misdelivered catalog. No courier. No signature. Just a brown envelope thick enough to feel like it had a spine. On the front, written in careful block letters:

FOR THE REPORTER WHO STILL BELIEVES FIRE CAN LIE.

Inside was a key taped to a note and a single sentence that made my stomach tighten before my brain caught up:

“THE MESSAGES THEY TOLD US TO BURN ARE NOT ALL ASH. COME TONIGHT. COME ALONE.”

An address followed—an aging apartment building near the river—and a time: 8:10 p.m. Not 8:00. Not 8:15. The kind of specificity that suggests someone spent a lifetime living by schedules that didn’t forgive mistakes.

I should’ve called my editor. I should’ve brought a colleague. I should’ve done ten sensible things.

Instead, I found myself standing in the building’s dim lobby, listening to the elevator cables hum like tired piano strings, holding that key like it might unlock more than a door.

Apartment 4C had no name on the buzzer. Just a piece of tape with a handwritten C.

I knocked once.

Then twice.

A man’s voice answered from behind the door—American English, but careful, as if each word had to pass inspection.

“Did anyone follow you?”

“No,” I said. “Not that I saw.”

There was a pause. A soft click. The door opened just wide enough for one eye to examine me.

He looked older than the voice suggested—thin, pale, the kind of face that had learned to be unreadable. His hair was white, but his posture still held a stiffness that felt practiced.

He opened the door fully. “Come in. Close it.”

Inside, the apartment smelled of black tea and old cardboard. Stacks of books lined the walls—history, linguistics, telecommunications, shelves of thick binders with blank spines. The lights were low, not romantic—defensive.

He gestured toward a chair beside a small table. On the table sat a metal box, the kind used to store tools, with a simple keyhole.

“That key,” he said, nodding toward the one in my hand, “belongs there.”

I didn’t move yet. “Who are you?”

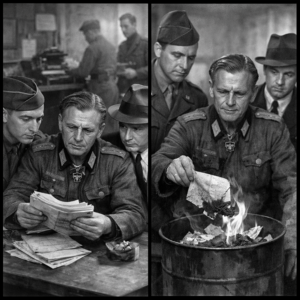

His eyes didn’t flinch. “A former communications officer. During the war. My job was to pass messages that were never meant to survive.”

“You wrote me,” I said.

“I did,” he replied. “Because the people who insisted those messages be destroyed are running out of time—and so am I.”

He said “messages” the way other people say “evidence.”

I sat. He remained standing, as if sitting would grant the room too much comfort.

“You want to tell a story,” he said. “Not a rumor. Not a legend. A story that can hold up under light.”

“That’s the goal,” I said carefully. “But if you’re asking me to publish claims, I’ll need proof.”

He almost smiled. “You will have more proof than you asked for.”

He slid the box closer. “Put the key in.”

The metal was cold beneath my fingertips. When I turned the key, the lock gave with a reluctant click, like it resented being useful.

Inside the box were three things:

-

A bundle of thin papers wrapped in oilcloth

-

A small notebook with a black cover

-

A sealed glass tube, like something meant for a laboratory

I lifted the notebook first. The cover was blank. No label. No title. The first page held a date and a line of handwriting that felt too neat to belong to anything dangerous:

“BURN AFTER READING: ORDERS ARE NOT OPTIONAL.”

I looked up. “These are copies?”

He nodded once. “Not originals. Not the ones that traveled through official channels. Those were destroyed. These are what survived because I refused to let my own hands erase them completely.”

“You kept them,” I said.

“I did,” he answered, voice flat. “And I’ve paid for it with a lifetime of listening for footsteps that never come.”

I set the notebook down gently. “What are we looking at?”

He lowered himself into the chair opposite me, slowly, like his joints argued with gravity.

“Toward the end,” he said, “we were told to burn everything that could embarrass anyone important.”

“Embarrass,” I repeated.

His eyes sharpened. “That’s the word they used. It was a clean word, meant to make the action feel clean. Like sweeping dust instead of burying a crime.”

I chose my next question carefully. “Who gave the order?”

He stared at the metal box as if it contained a living thing. “Names are easy to get wrong. I will not hand you names until you have the documents in your hands and experts have verified them. But the order came from above—above the people who thought they were in charge.”

He leaned forward. “Have you ever noticed how official history often has a gap right where the most important decisions should be?”

“Yes,” I said.

“That gap,” he whispered, “was created with fire.”

He reached into the box and tapped the glass tube. “This is why you came.”

I held it up to the light. Inside was a tight roll of something that looked like film.

“Microfilm,” I said.

“Copies,” he corrected. “Not complete. Not clean. But enough to show intent.”

I stared at the tube. “Why give it to me now?”

“Because someone has started visiting people like me,” he said quietly. “Old men with old hands. Asking friendly questions. Offering help. Collecting ‘donations’ of papers we’re too tired to protect.”

His mouth tightened. “They want to finish the job.”

The air in the room felt thinner.

“What’s your name?” I asked again.

He hesitated, then spoke as if it pained him to give even that much.

“Otto,” he said. “Just Otto.”

I didn’t push for more. Names can wait. Evidence cannot.

An hour later, I sat in the basement of a small university archive, in front of a machine that hummed like a sleepy engine. Otto had refused to come with me.

“I have done enough traveling toward the past,” he’d said, and his voice carried a finality that closed the subject.

So I brought the tube to someone I trusted: an archivist named Mara, whose entire career could be summarized by one sentence—she hated sloppy claims.

Mara glanced at the tube, then at me. “Where did you get this?”

“From someone who says it’s real.”

“That’s not an answer,” she said.

“It’s the only one I’m giving right now,” I replied.

She didn’t like it, but she liked the tube less. She loaded the microfilm carefully, like it might splinter into lies if handled roughly.

The first frame flickered onto the screen.

Then the second.

Then the third.

Each one was a typed message—short, clipped, formatted like an official transmission. There were date stamps. Routing marks. Reference numbers.

And at the bottom of each page, a line that made my skin prickle:

DESTROY AFTER READING.

Mara’s face changed. “This isn’t a diary. This is traffic.”

“Keep going,” I said.

She advanced the film.

A message appeared with a header that looked routine—logistics, relocation, administration. The content was dry enough to bore a casual reader, but I’d spent years reading language designed to hide meaning in plain sight. There were phrases that carried weight.

“REMOVE ALL DUPLICATE FILES.”

“TRANSFER CONTACT LISTS TO ‘SAFE STORAGE.’”

“REVISE ALL ROUTING RECORDS TO MATCH NEW INDEX.”

“BURN PAPER. KEEP PEOPLE.”

Mara swallowed. “That last line…”

“It’s not metaphor,” I said.

She advanced again.

Another message:

“ALL MATERIALS RELATED TO ‘ROOM 9’ ARE TO BE ELIMINATED. NO EXCEPTIONS. CONFIRM WITH ASH RECEIPT.”

“Ash receipt?” Mara echoed.

“A confirmation that the destruction happened,” I said. “A paper trail… for a paper fire.”

Mara’s eyes flicked toward me. “Someone knew future investigators would look for missing files. So they built proof that the files were destroyed ‘properly.’”

I stared at the screen. “A controlled erasure.”

Frame after frame rolled past. Some were mundane. Some were chilling in their calmness. None were sensational. That was what made them frightening.

They weren’t written by madmen.

They were written by managers.

Then we hit one message that shifted everything.

It was dated late in the war. The header included a routing path that suggested it moved quickly, bypassing normal steps. The content was brief:

“PRIORITY: BEGIN BURN PROTOCOL. INCLUDE CORRESPONDENCE REGARDING ‘TRANSFER OF ASSETS’ AND ‘PERSONNEL ARRANGEMENTS.’ IF ASKED, STATE ‘NO RECORDS EXIST.’”

I leaned closer, the words tightening around my throat.

“Personnel arrangements,” Mara murmured. “That could mean anything.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s why they used it.”

She advanced again, and the next frame carried a list of reference numbers—messages that were supposed to exist, according to the indexing… but had been removed.

A missing list inside a surviving list.

Otto had been right.

This wasn’t just about burning paper. It was about burning the map to the paper.

When I returned to my office that night, the hallway lights felt brighter than usual, like they were trying too hard to look innocent.

My laptop bag felt heavier. Not because the microfilm weighed anything. Because now I understood what it represented.

I called my editor and said only, “I have something. It needs verification and legal.”

She didn’t ask for drama. She asked for facts. That’s why I worked for her.

“Bring it in,” she said. “And don’t email it.”

Half an hour later, as I crossed the street, my phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number:

YOU’RE HOLDING ASH. DON’T LET IT DIRTY YOUR HANDS.

No signature. No threat. Just the kind of message meant to shrink you without leaving fingerprints.

I deleted it, then immediately regretted deleting it. Evidence has a way of becoming valuable right after you discard it.

The next morning, another message arrived—this time a printed envelope, slid under the newsroom door before dawn. Inside was a single sheet of paper: a “recommended” version of my story, softened until it became meaningless.

In the safe version, the messages were “unverified fragments.” The burn instructions were “standard wartime practice.” The missing references were “clerical inconsistencies.”

At the bottom, in pen:

PUBLISH THIS VERSION AND YOU’LL BE LEFT ALONE.

I stared at it for a long time.

Then I thought of Otto, sitting in his dim apartment, listening for footsteps that didn’t come.

I thought of that phrase on the screen:

BURN PAPER. KEEP PEOPLE.

Somebody still cared enough to offer me peace in exchange for silence.

Which meant the story still mattered.

Over the next week, we did it the hard way—the honest way.

We brought in a document examiner to analyze the typed formats and stamps. We compared the reference numbers to known routing systems from the period. We cross-checked phrases that appeared in the microfilm against surviving transmissions in public archives.

We found matches.

Not perfect. Not complete. But enough to prove the microfilm belonged to the same universe as official records—like a missing chapter from a book you thought you’d already finished.

Then came the strangest part: the reactions.

An archive that had previously agreed to pull a file suddenly “couldn’t locate it.”

A historian who had offered to comment suddenly stopped replying.

A retired specialist agreed to meet, then canceled twice, then sent a short email:

“I’m sorry. I can’t be connected to this.”

Nobody threatened us openly.

They didn’t have to.

They just tightened the world.

That’s how you know a story has pressure behind it: doors close quietly, and everyone pretends it’s because of the wind.

I went back to Otto one last time before we published.

His apartment looked the same—low light, stacks of binders, tea that had gone cold in its cup.

He listened while I summarized what we’d verified, what we couldn’t, and what we planned to say.

When I finished, he nodded once.

“They will call you dramatic,” he said. “They will say you are chasing ghosts.”

“I’m chasing paperwork,” I replied. “It’s less romantic.”

His mouth twitched. “Paperwork has ruined more lives than romance ever did.”

I hesitated. “Why did you keep the copies? Why not burn them like you were told?”

Otto stared at his hands for a long moment.

“Because the first time I watched a message burn,” he said softly, “I realized something: fire doesn’t destroy truth. It destroys the path to truth.”

He looked up, eyes sharp again. “And I realized another thing.”

“What?”

“The people who ordered the burning were calm,” he said. “They weren’t panicked. They weren’t afraid of losing the war. They were afraid of losing control of the story that would be told afterward.”

My throat tightened. “So you kept the story.”

“I kept a fragment,” he corrected. “A splinter. Enough to make forgetting painful.”

I reached into my bag and pulled out a copy of the “safe version” someone had left for me. I placed it on his table.

Otto read it slowly, then let it fall back onto the wood like it was contaminated.

“They offered you comfort,” he said.

“Yes.”

He nodded, almost sadly. “Then you are close.”

He stood, walked to the window, and stared at the river as if it could carry time downstream.

“I will not live to see what happens next,” he said, voice low. “But you will. And when they argue about motives, you must not let them escape the documents.”

“I won’t,” I said.

He didn’t turn around. “One more thing.”

“What?”

“Do not make it about me,” Otto said. “Do not make me a character. Make the evidence the character.”

I understood what he meant. If the story became about one old man’s confession, it could be dismissed as theater. If it became about a system’s written instructions, it would be much harder to wave away.

I left his apartment carrying not just proof—but responsibility.

We published on a Friday morning.

The headline was sharp but careful. The piece focused on what we could demonstrate:

-

That a “burn protocol” existed and was explicitly referenced in surviving transmissions

-

That certain message reference numbers were removed from indexes, creating deliberate gaps

-

That “destroy after reading” was not simply casual language but linked to confirmation procedures

-

That some instructions aimed not just to eliminate paper, but to reshape future records

-

That the microfilm matched formatting and routing conventions found in verified archival material

We did not sensationalize. We did not turn suffering into entertainment. We did what journalism is supposed to do: we put evidence where denial could see it.

The response was immediate.

Some readers accused us of exaggeration. Others demanded more names, more detail, more spectacle. But the most telling reaction came from institutions, not individuals.

Within days, a government archive announced “temporary access changes” for a group of wartime collections.

A museum quietly updated a timeline page, adding one line that had been missing for years.

And a historian with a reputation for caution sent me a message that read:

“I’ve been waiting for someone to find the ash receipts.”

Otto had told me to watch for the safe version. For the subtle pressure. For the polite requests.

We got them all.

A spokesperson offered an interview “to provide context,” but only if we agreed not to publish images of the documents.

An intermediary suggested we “donate” the microfilm to an institution that would “protect it,” which sounded a lot like burying it with better manners.

Then, late one night, my phone buzzed again.

A text from an unknown number:

FIRE IS CLEAN. PAPER IS MESSY. STOP MAKING IT MESSY.

I stared at the screen until it went dark.

They weren’t trying to argue with me.

They were trying to wear me down.

But the messages Otto saved weren’t ash anymore. They were part of the record now—scanned, verified, analyzed, and copied in ways fire couldn’t undo.

A week later, I returned to Otto’s building.

The lobby smelled the same—stale carpet and disinfectant—but the elevator felt slower, as if it didn’t want to carry anyone toward bad news.

When I knocked on Otto’s door, no one answered.

I knocked again.

Still nothing.

The next day, a neighbor told me an ambulance had come in the night. Quiet. No lights.

Otto was gone.

I never learned if he left peacefully or simply ran out of time the way he’d predicted. But I found something else: an envelope taped behind the mailbox panel downstairs, addressed to me in the same careful block letters as the first package.

Inside was a note, only two lines:

“THEY TAUGHT US TO TRUST FIRE.”

“SO I TRUSTED PAPER INSTEAD.”

No signature.

No drama.

Just a final, stubborn refusal to let the past be edited into comfort.

And in that refusal was the real story: not just that messages were ordered burned, but that someone understood the most dangerous trick of all—

If you erase the instructions, you can pretend the outcome was accidental.

Otto’s microfilm didn’t resurrect everything that was lost.

But it did something fire was never designed to allow:

It made forgetting inconvenient.

It made denial harder.

It made the truth—messy, stubborn, and human—survive the clean illusion of ash.