A 14-Year-Old’s Rattletrap Bicycle Looked Harmless—Until It Triggered the Midnight Sweep That Wiped a Nazi Command Staff Off the Map in One Night

No one remembered the day the bicycle arrived, only that it was suddenly there—leaning against the bakery wall like it had always belonged, paint faded to the color of rainwater and chain whining with every turn as if it hated moving forward.

In a town where people learned to keep their eyes down and their voices low, an old bicycle didn’t look like danger.

It looked like poverty.

It looked like a girl trying to be useful.

And that was exactly the point.

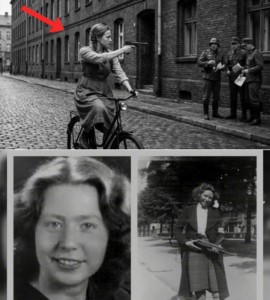

Her name was Elise Varga, fourteen years old, all elbows and sharp angles, with a face too young to wear the calm she’d practiced. In the mornings she carried bread for Madame Fournier. In the afternoons she delivered mended coats from the tailor. If anyone asked, she was simply running errands—because hungry families still needed food, and worn-out clothes still needed stitching, and nobody had enough time or courage left for complicated questions.

But Elise was also something else.

Not a hero. Not a soldier. Not even the romantic kind of secret agent people wrote about in safer years.

She was a messenger—the smallest, quietest gear in a machine that didn’t have room for noise.

The bicycle had a name among the Resistance: Bluebird.

Not because it was pretty. It wasn’t.

Because it flew under everyone’s attention.

And because—if you knew what to listen for—it could sing.

On the day Elise first rode Bluebird through the square, three officers stood outside the requisition office, laughing at something written on a clipboard. Their coats were clean, their boots polished, their faces relaxed in the way occupying men often looked when they believed the world belonged to them.

Elise kept her gaze soft, harmless. She pedaled steadily, basket rattling.

The bicycle chain squeaked—high and thin, like a mouse complaining.

One officer turned, annoyed by the noise.

“Fix that chain,” he called in accented French, as if giving advice to a child.

Elise smiled politely, like she was embarrassed.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

Then she rode on.

The officer returned to his conversation. His laugh resumed. The moment ended.

Only it didn’t, not really.

Because Elise had seen what she needed: the stamp on the clipboard, the timing of their cigarette break, the guard pattern by the office door, the way one of them kept glancing toward the bell tower as if checking for a signal.

Small things.

The kind of details nobody noticed unless they needed them.

That evening, Elise rolled Bluebird into the back of the bakery and closed the door behind her. The air smelled of yeast and flour and the day’s exhaustion. Madame Fournier—round and stern, with hands that could knead dough into obedience—didn’t ask questions. She never did. She simply nodded toward the cellar.

Elise went down the steps.

In the dim light, three people waited around a table: a schoolteacher who no longer taught, a mechanic with oil permanently in his nails, and a priest who’d stopped writing sermons and started writing names.

They didn’t greet Elise with affection. Affection was dangerous. It made you careless.

The mechanic slid a paper across the table.

Elise studied the marks: simple lines and numbers arranged like a child’s arithmetic.

To an enemy, it would have been nothing.

To Elise, it was a route—streets, hours, corners where someone would be watching.

“Same as yesterday?” Elise asked.

The priest shook his head. “Different today. New visitors in town.”

“How many?” Elise asked.

The schoolteacher lifted two fingers, then one more.

“Three,” she said. “But they bring a shadow with them.”

Elise frowned. “A shadow?”

The mechanic tapped the paper twice, then pointed to a small symbol in the margin: a circle crossed by a line.

“Command,” he said quietly. “Not the usual men.”

Elise’s throat tightened. She’d heard whispers about command visitors: men who arrived in clean cars, inspected maps, issued orders, then left before anyone could learn their names. When they came, bad things followed—raids, arrests, disappearances that left families staring at empty chairs.

Elise looked at Bluebird leaning against the cellar wall.

The bicycle didn’t look capable of changing anything.

But then, neither did Elise.

“What do you want me to do?” she asked.

The priest pushed a small object toward her on the table. It looked like an ordinary trinket: a metal charm on a bit of string, the kind of thing a girl might hang from her handlebar for luck.

Elise picked it up.

It was heavier than it looked.

“Ride your route,” the priest said. “Be seen. Be ordinary. And if you see the silver car—”

Elise’s eyes lifted.

“—ring your bell twice at the fountain,” the schoolteacher finished.

Elise stared at them, then nodded once, very small.

“Twice,” she repeated.

“Twice,” the mechanic echoed.

Madame Fournier’s voice floated down from the bakery above, calling, “Elise! The bread is cooling!”

Elise stood and tucked the charm into her pocket like it was a peppermint.

She took a breath, placed her hands on Bluebird’s handlebars, and wheeled the bicycle up the stairs.

Above her, the town continued pretending.

Below her, the machine of quiet resistance turned another notch.

For weeks, Elise’s life looked the same to anyone watching.

A girl riding a bicycle.

A basket of bread.

A scarf wrapped too tight against the cold.

She stopped at the tailor. She stopped at the butcher. She stopped at the church, where she pretended to pray while her eyes counted boots and her ears counted voices.

Sometimes she saw the same officers again—always laughing, always certain.

Sometimes she saw different ones.

And sometimes, on days that felt too still, she saw the silver car.

It moved like it didn’t belong on these streets—too clean, too smooth. It passed without splashing mud, as if it carried its own private air.

The first time Elise spotted it, she nearly forgot to breathe.

It paused near the requisition office. A man stepped out wearing a long coat and gloves, his posture tight, controlled. He didn’t smile. He didn’t look around like a tourist. He looked around like a man measuring a room before he decided how to rearrange it.

Elise kept pedaling.

Her bell sat under her thumb like a sleeping animal.

She didn’t ring it yet.

Not until she reached the fountain in the center square, where the water ran thin and constant, where women filled buckets in silence, and where guards pretended not to see.

Elise circled once, as if she’d forgotten something.

Then she rang the bicycle bell twice.

Ding. Ding.

It sounded innocent—bright, childish.

A woman carrying laundry didn’t flinch. A man with a sack of potatoes kept walking.

But at the far edge of the square, a boy leaning against a wall—too still, too quiet—tilted his head and scratched his ear.

Then he walked away.

Elise continued on.

Her heart hammered against her ribs so hard she feared the entire square could hear it.

Bluebird’s chain squeaked again, complaining.

She whispered under her breath, “Quiet.”

The bicycle, of course, didn’t listen.

That night, the town’s air changed.

Not in a way you could point to. Not like thunder announcing itself.

More like the hush that falls before a door opens.

Elise lay in bed with her coat folded beside her and her shoes placed carefully under the chair, ready. She’d learned that sleep in occupied territory wasn’t really sleep; it was waiting with your eyes closed.

From somewhere down the street, she heard a car engine cut out.

Then another.

Then—faintly—voices.

She sat up.

Her mother stirred in the other bed, eyes opening instantly. Mothers didn’t sleep either.

“Elise,” her mother whispered. “Don’t move.”

Elise didn’t answer. She listened.

Boots.

Not one pair.

Many.

They moved with a rhythm that didn’t belong to ordinary patrols. Ordinary patrols were lazy, bored. These steps were quick, precise—like a list was being followed.

Elise’s fingers tightened on the blanket.

A sharp knock sounded from a neighbor’s house.

A door opened.

A muffled exchange.

A door closed again, harder.

Elise’s mother grabbed her wrist, nails pressing through skin.

“Promise me,” her mother whispered. “Promise me you will stay.”

Elise swallowed.

She wanted to promise. She did.

But she also had a memory of the priest’s eyes in the cellar, the mechanic’s hands trembling around a cigarette, the schoolteacher’s voice steady because it had to be.

She leaned closer to her mother.

“I’ll be careful,” Elise whispered.

Her mother’s jaw tightened. “That’s not a promise.”

Elise didn’t reply. She slid out of bed, moved like a shadow, and eased the window open just enough to slip through.

Cold air hit her like a slap.

She landed softly in the narrow side alley behind their building, where Bluebird was hidden under a tarp. Her fingers ripped the tarp away and found the handlebars. The bicycle’s metal was icy.

“Please,” Elise breathed, not sure who she was asking. “Please.”

She wheeled Bluebird forward, taking care not to make the chain squeal. It squealed anyway, quiet but stubborn.

She pushed the bicycle rather than riding, keeping to shadows, moving toward the bakery. Madame Fournier’s cellar was the closest safe place she knew.

Halfway there, she saw them.

A line of men in coats, moving through the street like a tide.

They stopped at one house, knocked once, then entered.

A minute later, they emerged with two men between them, hands bound, heads down.

Elise froze behind a stack of crates.

Her breath fogged in front of her face.

One of the bound men lifted his head slightly. Even in the dim light, Elise recognized him: the mechanic’s brother. A man who fixed radios and pretended they were toasters.

Elise’s throat tightened.

This wasn’t random.

This was a sweep.

And it wasn’t targeting the town in general—it was targeting something specific, like a net thrown over a fish you’d already spotted.

She looked past the line of men and saw the silver car parked at the corner, its windows dark.

The man in gloves stood near it, watching.

Elise’s mind did something strange: it went calm.

Because calm was what happened when fear ran out of places to go.

Bluebird’s bell sat under her thumb again.

And suddenly she understood the bicycle’s real purpose.

It wasn’t a weapon.

It was a trigger.

A way to pull the town’s invisible strings at the exact moment they needed to tighten.

Elise backed away from the crates and turned, pushing Bluebird into a side lane.

She didn’t go to the bakery.

She went to the bell tower.

The bell tower was old, stone damp with age, stairs curling upward into darkness. Elise had climbed it once as a child on a school trip, when the war still felt far away and teachers still smiled.

Now it felt like a throat.

She guided Bluebird inside and pulled the door shut behind her. The air smelled of dust and cold metal. Her breath echoed.

Her hands shook as she climbed the stairs, the bicycle half-lifted, half-dragged, its chain complaining at every bump.

By the time she reached the narrow landing near the bell, her arms burned.

She set Bluebird down and pressed her forehead against the bicycle’s handlebars, breathing hard.

Then she did the thing she’d been trained—quietly, carefully—to do without ever being told it was training.

She listened.

Outside, the sweep continued. Doors opened. Voices barked. People were pulled into the street.

Elise reached into her pocket and pulled out the “charm” the priest had given her. In the dim light, it looked even more harmless: a small metal piece, plain, forgettable.

She held it up, then set it against the stone ledge of the bell tower’s slit window.

From this angle she could see the square.

She could see the silver car.

She could see the gloved man turning his head, impatient.

And she could see something else, something that made her stomach drop:

A group of officers—more than a dozen—walking toward the requisition office together, gathered like this night mattered enough to cluster.

They moved with purpose, protected by guards who spread around them.

A meeting.

Right now.

Right here.

Elise’s mind raced.

If the Resistance knew the officers were gathered, they could act.

But acting didn’t mean what the movies meant. It didn’t mean a dramatic showdown. It meant pulling a thread already prepared, letting the occupying machine stumble over its own certainty.

Elise gripped Bluebird’s handlebar so hard her knuckles whitened.

She didn’t have a radio. She didn’t have a weapon. She didn’t have time.

She had only what she’d always had:

A bicycle.

A bell.

And the town’s habit of ignoring a child.

Elise took a breath and did the boldest, simplest thing imaginable.

She rang Bluebird’s bell—once.

Ding.

She waited three heartbeats.

Then she rang it again—twice, fast.

Ding-ding.

To anyone else, it was nothing.

To the people who knew, it meant:

They’re gathered. It’s now.

Elise pressed herself against the stone, staring down at the square as if her gaze could carry the message faster.

A minute passed.

Two.

Then she saw movement that didn’t belong.

A bread cart rolled into the square—too late for deliveries, pushed by a man with his cap pulled low. Another cart followed, then another. They weren’t aligned like merchants. They drifted, slow, casual, like people who had all decided at once to become clumsy.

The gloved man near the silver car narrowed his eyes.

One officer pointed toward the carts, irritated.

Then, from the far side of the square, a familiar figure appeared: Madame Fournier.

She walked with her usual heavy confidence, carrying a basket like she owned the street. Nobody stopped her, because nobody wanted to deal with a baker unless absolutely necessary.

She reached the fountain and paused—just long enough to adjust her scarf.

And in that motion, Elise saw it: a slip of paper pressed into the stone rim of the fountain, tucked where only someone looking for it would notice.

A guard glanced at Madame Fournier, suspicious.

Madame Fournier stared back, expression flat, like she’d baked bread through two wars and would bake through ten more.

The guard looked away first.

Elise’s throat tightened.

The town was moving.

Not loudly.

Not openly.

But it was moving.

The sweep reached the bakery.

Elise heard it before she saw it: the knock, the shouted words, the cellar door slamming open. She gripped the stone ledge until her fingers hurt.

In the square below, the group of officers had reached the requisition office steps. They paused, tightening their cluster.

The gloved man stepped forward, impatient now.

Something had gone wrong, he could feel it. Men like him always could.

He snapped an order to a guard. The guard jogged toward the fountain, eyes scanning.

He looked right at the carts. Right at Madame Fournier. Right at the fountain.

But he didn’t look up.

He didn’t think to.

Why would he?

A bell tower was just a bell tower.

A girl was just a girl.

A bicycle was just a bicycle.

Then, like a curtain being pulled, the square’s atmosphere shifted. Not with noise. With coordination.

The bread carts stopped, subtly blocking the street edges. Not like barricades—like accidents.

A man dropped a sack of flour, spilling white powder across cobblestones like sudden snow. Guards stepped back instinctively, their boots sliding.

Madame Fournier picked up her basket and walked away at the exact moment the gloved man turned toward the requisition office door.

And that’s when the hidden door inside the requisition office opened from the rear—an entrance most townspeople didn’t even know existed.

Uniformed men emerged—different uniforms. Not occupying uniforms.

They moved fast, silent, disciplined.

Elise’s breath caught.

A raid—not by the town, but by an organized force that had been waiting for the exact moment these officers gathered.

The officers froze, confusion flashing across faces used to causing fear, not feeling it.

The gloved man’s hand moved toward his coat.

He didn’t finish.

Someone behind him seized his arms and pinned them. The motion was controlled, practiced, like a door being shut.

The square erupted into shouting—orders, protests, the scrape of boots, the sudden chaos of men realizing their power had a boundary after all.

Elise’s eyes burned.

It didn’t look like a battle. It looked like a clockwork trap snapping shut.

Within minutes, the officers were being marched—not in a proud line like Elise had been marched in her nightmares, but in a tight, controlled group, their heads down, their confidence gone.

Dozens.

Not harmed in the dramatic way stories loved, but removed—taken out of the town’s air, out of its future nights.

Elise’s breath shook as she watched.

The gloved man twisted his head once, scanning, furious, searching for the crack that had let this happen.

His eyes flicked to the fountain. The carts. The flour.

He still didn’t look up.

Because men like him couldn’t imagine a bicycle bell starting their downfall.

Elise didn’t wait to see what happened next.

She knew better than anyone that a plan could succeed and still turn ugly in its aftermath.

She grabbed Bluebird’s handlebars and pulled the bicycle away from the slit window. She began dragging it down the spiral stairs, silent as she could, heart still hammering.

Halfway down, she heard the bell above vibrate slightly from the air’s movement, as if the tower itself were reacting.

She reached the ground floor, eased the door open, and slipped out into the alley.

The town’s streets were chaotic now—guards running, neighbors peering from behind curtains, doors opening and closing like nervous blinking.

Elise pushed Bluebird toward home, keeping to side lanes.

A man grabbed her arm suddenly.

Elise jerked, panic flashing.

Then she saw who it was: the schoolteacher, face pale, eyes fierce.

“You did it,” the teacher whispered.

Elise swallowed. “Did—did it work?”

The teacher’s mouth trembled, almost a smile. “They’re gone. The visitors. The men who wrote the lists.”

Elise’s knees nearly gave out.

The teacher squeezed Elise’s arm, then released her quickly, looking around.

“Go home,” she hissed. “Be a child again. Right now.”

Elise nodded, blinking hard.

She pushed Bluebird through the alleyway toward her building. When she climbed back through the window, her mother was standing there, eyes wet, face furious and relieved all at once.

Her mother slapped Elise’s cheek—not hard, but enough to bring Elise fully back into her body.

Then her mother pulled her into a crushing hug.

“You will break my heart,” her mother whispered into her hair.

Elise’s voice came out small. “I didn’t mean to.”

Her mother held her tighter. “That doesn’t matter.”

Elise closed her eyes, listening to the distant commotion fading into something else: the strange, stunned quiet of a town realizing it had, for one night, pushed back.

In the weeks that followed, rumors swelled and shifted.

Some people said Allied forces had acted on a tip.

Some said the Resistance had infiltrated the requisition office months ago.

Some whispered that the officers had been moved to stand trial after the war, that their names were recorded, that their power ended not with a dramatic spectacle but with paperwork, handcuffs, and a door closing behind them.

And in nearly every version, people tried to add something bigger.

A secret device. A dangerous contraption. A miraculous trick hidden in the bicycle.

But the truth—what Elise understood in her bones—was less theatrical and more haunting.

Bluebird didn’t “do” anything on its own.

It simply allowed a fourteen-year-old to be everywhere without being seen.

It let her notice patterns.

It let her deliver timing.

It let her ring a bell at the right moment and tell an entire invisible network: now.

That was the miracle nobody wanted to admit.

Not a weapon.

A signal.

A child overlooked.

A town listening.

One night, the bicycle chain squeaked through the square again. Elise rode Bluebird slowly past the fountain, basket empty, face neutral.

An officer—new one, younger, less confident—looked at her with irritation.

“That noise,” he muttered. “Fix your chain.”

Elise smiled politely.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

Then she pedaled on, letting the chain squeal, letting the bell remain quiet.

Because the bell didn’t ring every day.

It rang only when the town needed the world to change.

And long after the war ended—long after the uniforms vanished and the requisition office became just another building—people in that town still remembered the strangest detail of all:

The night dozens of powerful men were suddenly gone…

…and the only thing anyone could swear they heard beforehand was an “innocent” bicycle bell, ringing like a child’s toy, in a square that had forgotten how to hope.